Your ABA

Self-help centers could better serve consumers by helping them find lawyers, survey indicates

Photo of Bonnie Hough courtesy of the Center for Families, Children and the Courts for the Judicial Council of California

But Bonnie Hough, who works with pro se litigants in San Francisco, says a new national survey is calling attention to yet another gap: consumers who can afford legal services but still aren't getting them.

The market of consumers who can pay for lawyers was apparent in the recently released Self-Help Center Census: A National Survey (PDF), conducted by the ABA Standing Committee on the Delivery of Legal Services.

Hough, a committee member, says it's no surprise that many of the nearly 3.7 million people estimated to be served by self-help centers annually are poor. But she says there's also a sizable segment who can afford to pay for legal services, and lawyers would benefit from efforts to figure out how to create an effective pipeline between the two groups.

"This survey really shows that self-help centers are an effective service-delivery mechanism," says Hough, whose job as managing attorney for the Center for Families, Children and the Courts for the Judicial Council of California is to help San Francisco courts respond to the needs of self-represented litigants. "They're providing a lot of services, and the concept is clearly spreading because there are more centers in place than in the past. That's the good news."

But the question remains of how to connect those who can afford to pay with lawyers who can help them.

"That's where the committee is really interested in focusing its future efforts, and I hope attorneys will be looking at this analysis and realizing there's an untapped market there," Hough says.

In the 20 years since the first legal self-help center was created in Maricopa County, Arizona, Hough has witnessed the growth of the concept. Self-help centers were introduced in California not long after, about 17 years ago, to a wary judiciary.

"In California at the time, there was a perception among the judges: ‘We don't really need this because we don't see that many people needing help; and when they do come in, we can make sure they get what they need,' " she recalls. "Then, in Los Angeles, the self-help center was seeing 3,000 people a month in the first few months.

"Today when you look at the number of people being served, it's just extraordinary," Hough says. "Also, often one thing a self-help center can do and do very well is to explain to customers why, in their circumstance, it makes sense to hire a lawyer. They can say, ‘I know this seems simple, but let me explain what's happening. I can't take the case, but I see you own a house, and here's why it makes sense to hire a lawyer to protect your house.' "

NATIONWIDE GROWTH

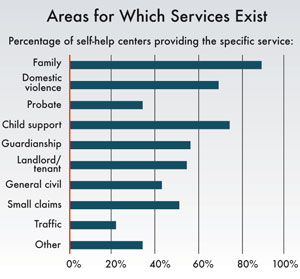

The survey data shows similar growth in most of the country. The committee identified about 500 self-help centers in more than 36 jurisdictions and sent an online survey. Representatives of roughly 47 percent of those centers, or about 222, in 30 states and the District of Columbia responded.Family law and child support are the most common areas of the law for which customers receive services. Other common services cover domestic violence, guardianships, landlord/tenant matters, small claims and general civil matters.

California and Illinois have the most centers, though the facilities are fundamentally different. California's court-based centers must be staffed by attorneys and support personnel directed by attorneys. In Illinois, many centers are located in public libraries with volunteer staffing.

Connecticut, Florida and Maryland also reported a significant number of centers. However, no centers from the midsection of the country—from North Dakota all the way down to Alabama, along with a patch covering Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky and the Virginias—responded to the survey.

"There are certainly transportation issues with some of those states," Hough says. "In California, we have huge density, so we can have a self-help center in every court and in every county."

In the future, those gaps in service may be filled as self-help centers find ways to serve those who can't easily seek help in person. Hough says some programs are offering more telephone and online assistance.

"Alaska's is really done all by telephone and Internet, and then the centers send someone to court to help people resolve their cases," she says. "They can do a lot of the basic ‘How do you fill out the forms?' by phone, which makes a lot of sense. That's a very interesting model."

Minnesota blends the personal and technology-based models. Hough says it has an in-person center in Hennepin County, which encompasses Minneapolis and St. Paul, and then offers telephone and Internet services to residents throughout the rest of the state.

Additional systems are being deployed in spot locations. One center in California, for example, serves three counties—some of it via Skype when, say, a resident who doesn't speak fluent English needs to consult with a bilingual lawyer.

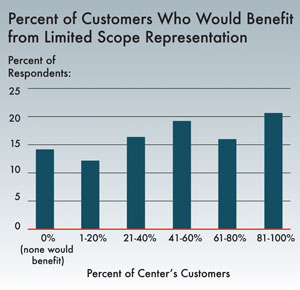

Two particular data points lead Hough to conclude that unbundled services may be an effective method of delivering legal services to even more consumers in the future.

UNBUNDLED UP

A measurable number of survey respondents believe at least some of their customers can afford to pay something for legal services. About 81 percent said fewer than one-quarter of their customers could afford to pay the going rate for legal services in their area. However, 19 percent said more than one-quarter of their customers could afford services at local rates. Also, 81 percent of respondents said they turned people away because the matters were too complicated or not the type of case handled by the center."We talk about unbundled services all the time because it really does fit into delivery mechanisms for our group, which is low- to moderate-income people," says William T. Hogan III, the committee's chair and a partner at Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough in Boston. "When the centers came out, one of the issues that came up in just about every case is that people would need the services of a lawyer, but that lawyer needs to be able to do limited-scope representation."

Hough expects that to be a big part of the committee's future focus. "I think they're going to spend time trying to figure out how to really develop this pipeline from self-help centers to the attorneys who can help with parts of a case and to really encourage limited-scope representation and unbundling."

That may also come organically through more interaction among the centers. Hough says the committee is hoping to post a directory of centers online so people throughout the country can identify resources available. That, she believes, will trigger those that weren't initially counted into coming forward and will facilitate even more information-sharing among the centers.

"The idea is to continue to encourage the model and the sharing of best practices," Hough explains. "This is a really new way of providing legal assistance. It's very practical and very much ‘Here's information for you to proceed with your case to make the right decisions for you' without establishing an attorney-client relationship."

This article originally appeared in the February 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: "Next Step: Referrals: Self-help centers could better serve consumers by helping them find lawyers, survey indicates."

Sidebar

Graphic by Jeff Dionise

Self-Help Services Focus on Domestic Relations Law

Self-help centers around the United States provide services most often in the substantive areas of family law, domestic violence and child support, but services are provided for several other types of civil matters, as well. The survey conducted in 2014 by the ABA Standing Committee on the Delivery of Legal Services received responses from 222 self-help centers in 28 jurisdictions.

Graphic by Jeff Dionise