Seeking justice in the killing fields

Associated Press

Even as Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital city, hurtles into the future, it can’t quite escape the past. At rush hour, the city’s tree-lined boulevards are clogged with Range Rovers and rusted bicycles alike. But not even the noise of Phnom Penh’s madcap traffic can compete with the sound of construction. One by one, high-rise buildings are going up, creating a skyline that looms over former French colonial villas and the shiny spires of Buddhist pagodas. Here is a city on the move, eager to join the ranks of Bangkok, Saigon—perhaps even Singapore. It doesn’t seem to have the time or the inclination to disturb the scars of the past.

But the scars are there, just below the surface. Strike up a conversation with a Cambodian in a cafe or start talking with the driver of your motorcycle taxi, and before long you’re likely to be casually told a story of such sadness and horror that it stings.

Or visit the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, on the grounds of one of the most notorious—and deadly—detention centers operated by the Khmer Rouge regime during its reign of terror from 1975 to 1979. The sun-bleached posters on the second floor of the museum are in shambles. The faces of surviving members of the regime’s leadership stare out from under layers of graffiti. In some of the posters, the eyes are scratched out; in others, the entire head is obliterated. Scrawled across all of them, in Khmer and English, French and Chinese, are comments of searing bitterness.

After the French granted Cambodia independence in 1953, the nation entered a period that alternated between promise and uncertainty. Norodom Sihanouk ruled the nation for 15 years starting in 1955, and many Cambodians consider the 1960s something of a golden age. But as the war in Vietnam intensified next door, Cambodia’s economy weakened and Sihanouk’s popularity began to decline. Although Cambodia proclaimed neutrality, North Vietnam was allowed to station troops on the Cambodian side of the border.

Sihanouk was overthrown in 1970 while out of the country and replaced by a U.S.-backed regime whose conduct ranged from inept to despotic. By then, a clandestine communist party had begun to gain strength in Cambodia. In 1975, the communists, labeled the Khmer Rouge and led by a former schoolteacher who adopted the name Pol Pot, came to power with plans to remake Cambodian society following radical Maoist models. The Khmer Rouge abolished private property, money, religion and schools. The cities were emptied as the regime sent almost the entire population to live in collectives in an effort to convert the country into an agrarian society. The Khmer Rouge killed hundreds of thousands of supporters of the former regime and alleged traitors, and hundreds of thousands more died of overwork and malnutrition.

Family ties were deemed meaningless. Marriages were arranged by the state and conducted en masse. Children were expected to inform on parents. “Angkar [a term used by the Khmer Rouge leadership to describe itself] has more eyes than a pineapple” was one of the Khmer Rouge’s famous warnings. “To keep you is no benefit, to lose you no loss” was another.

An estimated 1.7 million Cambodians died during the three years, eight months and 20 days the Khmer Rouge terrorized the country. In early 1979, the regime was overthrown by the Vietnamese army, which occupied Cambodia for the next decade.

And yet, the Khmer Rouge never completely disappeared, and it continues to cast a shadow over Cambodian politics and society. Many former functionaries of the regime are now members of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party. Hun Sen, a former low-ranking Khmer Rouge military commander who defected and helped the Vietnamese army overthrow the regime, has consolidated his power as prime minister, a post he has held since 1985. Nevertheless, Cambodia has achieved a semblance of peace and stability under Hun Sen’s leadership and developed ties with the international community. Hun Sen also began the process of bringing some leaders of Pol Pot’s regime to justice.

Such a gesture has deep significance in this country of 14 million people, where virtually every family was touched by the brutality of the Khmer Rouge. While some victims prefer to forget that past, and others want revenge, what many people seek, above all, is justice.

“Genocide has destroyed their family members, their life, but to fight genocide they come together as one,” says Youk Chhang. The executive director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, the country’s only independent Khmer Rouge research center, Chhang has spent the better part of the past 15 years collecting hundreds of thousands of papers, photos and films, and interviewing thousands of survivors and former Khmer Rouge. He says the evidence will ensure that people won’t forget what happened.

Khieu Samphan, a former Khmer Rouge head of state, at a hearing of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia in February 2009. He was arrested and placed under provisional detention in November 2007. Photo by Associated Press.

A DELICATE BLEND

Like Cambodia’s politics, the hunt for justice is full of complexity. The primary vehicle for pursuing that elusive goal is the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, commonly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. The tribunal is a delicate blend of judges, prosecutors, procedures and substantive law from both Cambodia and the international community. The ECCC website describes the body as “a Cambodian court with international participation that will apply international standards.”

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal is the product of political priorities as much as legal ideals. The tribunal came into existence after a decade of fits and starts in negotiations between the Cambodian government, the United Nations and officials of several nations, including the United States, interested in seeing a tribunal created. In June 1997, Prince Norodom Ranariddh and Hun Sen, who were sharing the duties of prime minister, sent a joint letter to U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan asking for assistance from the international community “in bringing to justice those persons responsible for the genocide and crimes against humanity during the rule of the Khmer Rouge.” The letter acknowledged that Cambodia did not have the resources or legal expertise to do the job on its own.

The creation of a tribunal offered clear political advantages for Hun Sen, whose efforts to maintain internal stability while consolidating his own power were predicated on showing a commitment to bringing some key Khmer Rouge leaders to justice without alienating the large numbers of former Khmer Rouge who still were a significant presence in the country. Hun Sen tipped his political hand when he ousted Ranariddh during a coup only a month after they sent their joint letter to Annan.

Hun Sen’s power play put a damper on negotiations to establish the tribunal. Interest also waned as the capture of Pol Pot, who had been in hiding along the Thai border, became less likely. (He died, under mysterious circumstances, in April 1998.) Talks lurched along for nearly a decade until an agreement between Cambodia and the U.N. finally entered into force in April 2005. Judges and prosecutors representing Cambodia and the international community were sworn into office in July 2006.

Nearly seven years later, the role of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal remains a matter of intense debate, both within Cambodia and among experts in the international human rights field.

“For now it’s the best process available” for Cambodia, says Chea Vannath, a political analyst and former president of the Center for Social Development, a nongovernmental organization that promotes democratic values in Cambodia. “I am sure that later on in the future, there will be something else more to satisfy needs of people. But for now, this is the best we can think of. And we are lucky to have it. Cambodia is out of long-lasting conflict, and what it needs is peace and stability. How to balance peace, stability, reconciliation? Yes, there is some degree of politicization of the process of course, but it remains useful.”

Speaking from an international perspective, however, David M. Crane is less restrained in his assessment of the tribunal. “The ECCC was the final and only hope for seeking some justice for the victims of the killing fields,” says Crane, a professor at Syracuse University College of Law, who served as the first chief prosecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone from 2002 to 2005. “The solution was certainly an ‘ugly baby’, a dual-headed hydra of built-in inefficiency all due to the political reality of its creation. Note, the ECCC is not a good marker for where the present state of modern international criminal law is today. It will deliver some justice and be used as a case study of how not to seek justice for victims of atrocity.”

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal’s chief advocate within the international community is David Scheffer. He was involved in the negotiations to create the tribunal in the 1990s, when he served as the first U.S. ambassador-at-large for war crimes issues during the final years of the Clinton administration. Scheffer, who is director of the Center for International Human Rights at Northwestern University School of Law in Chicago, now serves as the U.N. secretary-general’s special expert on United Nations assistance to the Khmer Rouge trials. One of his tasks is raising funds from outside governments and other sources. Because the tribunal gets no money from the U.N. or the Cambodian government, those contributions are vital to its existence.

Scheffer says his pitch to leaders of outside governments is simple: “This is the court that seeks to render justice for a greater number of people than any other court,” including the International Criminal Court, he says. “This is the big one. Yes, it’s taken a while to get there, but the Nuremberg trials of our time are taking place right in Phnom Penh, and we have the opportunity to support them.”

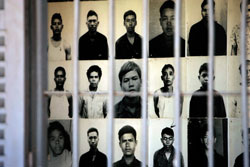

A tourist walks past a portrait of a former prisoner of the Khmer Rouge regime at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh. Photo by Associated Press.

A GRAND EXPERIMENT

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal is one of a small number of courts around the world that are engaged in a grand experiment in international human rights law. Starting in the early 1990s, they were created on an ad hoc basis for the purpose of bringing to trial individuals charged with bearing the greatest responsibility for carrying out war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other violations of international humanitarian law in the course of civil wars and other internal conflicts.

These tribunals operate outside the scope of the International Criminal Court. The ICC came into existence a decade ago in accordance with terms of the Rome Statute adopted in July 1998. The statute empowers the ICC, based in The Hague, Netherlands, to investigate and try individuals for violations of the most serious crimes of concern to the international community: genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. The court is an independent international organization and is not part of the U.N., although the Security Council may refer cases to the court’s chief prosecutor. The court has been ratified by 121 nations, including Cambodia. (The United States is one of the key holdouts.)

The ICC lacks jurisdiction over crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge in the late 1970s because it may deal only with alleged violations of international law that occurred after July 1, 2002, the date it came into existence.

But even if time frame were not an issue, the ICC would not have carte blanche to pursue Khmer Rouge members because its jurisdiction is limited under the principle of complementarity. “The court is intended to complement, not to replace, national criminal justice systems,” the ICC states on its website. “It can prosecute cases only if national justice systems do not carry out proceedings or when they claim to do so but in reality are unwilling or unable to carry out such proceedings genuinely.”

The limitations on the ICC’s jurisdiction make ad hoc tribunals a viable alternative, says Scheffer, who led the U.S. delegation during negotiations on the ICC statute in Rome. “The reality is that the ICC has a fractured jurisdiction around the world,” he says. “That leaves open many opportunities for accountability that we have to still think about creating new courts for. The question now is: What’s the model for an ad hoc tribunal if the International Criminal Court cannot get jurisdiction?”

The gold standards for such tribunals are the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, created in 1993 to prosecute alleged perpetrators of war crimes and related violations of international law during fighting in the Balkans in the early 1990s, and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, created in 1994 to prosecute those responsible for committing genocide and other crimes during a civil war that engulfed the country for nearly the entire year. Both courts have enjoyed a notable measure of success. The ICTY, based in The Hague, has charged more than 160 people, resulting in more than 60 convictions. More than 30 cases are in various stages of proceedings. The ICTR, based in Arusha in the United Republic of Tanzania, has completed 72 cases, including 10 acquittals, with one case still in progress.

But the Yugoslavia and Rwanda tribunals have advantages that other ad hoc courts have not had. They were both created directly by the U.N. Security Council, which guaranteed that they would receive adequate funding. In addition, both tribunals were created without the involvement of national governments and have used panels of international judges, making it easier for them to avoid political interference compromising their independence and to develop effective rules for conducting investigations and trials.

That has not been the case with other ad hoc tribunals created after the ICTY and ICTR. The Special Court for Sierra Leone was created jointly in 2002 by the U.N. and the Sierra Leone government to try individuals who bear the greatest responsibility for serious violations of international humanitarian law during a civil war that began in 1991. And the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, created in 2007 by the U.N. Security Council at the request of a majority of members of the Lebanese parliament, is composed of Lebanese and international judges who conduct trials under Lebanese criminal law. (The primary mandate of the Lebanon tribunal is to try those accused of carrying out an attack in February 2005 that killed former prime minister Rafiq Hariri and 22 others.)

But it is the Khmer Rouge Tribunal in Cambodia that embodies the joint domestic-international approach more than any other ad hoc tribunal now in existence.

David Scheffer serves as the secretary-general’s special expert on U.N. assistance to the Khmer Rouge trials. Photo by Wayne Slezak.

BALANCE OF POWER

All of the ad hoc tribunals now in existence are complex legal mechanisms, but the effort to create a tribunal operated in tandem by the Cambodians and the U.N. produced a structure that is notably intricate—and very nearly unwieldy.

The law and procedure applied by the tribunal is grounded in French civil law, which is the basis for the former French colony’s legal system, but incorporates a number of common-law elements as well. In accordance with the tribunal’s civil-law underpinnings, preliminary investigations are conducted by co-prosecutors (one Cambodian and the other nominated by the U.N.), whose introductory reports may lead to investigations by the co-investigating judges—again, one Cambodian and one from the U.N.—who also are empowered to question suspects and victims, hear from witnesses and collect evidence. The co-prosecutors present cases at trial and handle appeals.

Suspects must provide their own defense, but a separate section of the tribunal provides support services for suspects and their counsel. In addition, a civil parties section was created to provide support for victims and their relatives and representatives. Lawyers for the civil parties have the same rights to question witnesses at trial as lawyers for the prosecution and defense.

The tribunal occupies a modern, cream-colored building that looms over farmland quickly being overtaken by garment factories on the far outskirts of Phnom Penh. Some interpret a message in that location. The government refused to house the court in the city center, instead placing it adjacent to a military headquarters nearly an hour away. Most days that court is in session, scores of visitors are bused in from distant provinces. Poor and rich, young and old, they stream into a gallery that resembles nothing so much as a lecture hall, pop on headphones—proceedings are simultaneously translated into French, English and Khmer—and watch the action unfold behind the glass fishbowl that is occupied by defendants, lawyers and judges.

A key element of the negotiations that created the tribunal centered on how its makeup would balance the power of Cambodians and international representatives in its judicial chambers, prosecutor’s office and administrative staff. The negotiations led to a formula under which the tribunal’s pretrial chamber and trial chamber are made up of three judges from Cambodia and two international judges appointed by the U.N., while the seven-member supreme court chamber is made up of four Cambodian judges and three international judges. But to offset the numbers advantage for the Cambodian judges, the rules for the tribunal require that all decisions by the pretrial and trial chambers be agreed to by a vote of four judges, and decisions of the supreme court chamber must be agreed to by a vote of five judges.

Despite the checks created by this equation, some observers express serious concerns that the Khmer Rouge Tribunal is susceptible to widespread interference by the Cambodian government, which already tends to run roughshod over the nation’s domestic courts.

“I definitely think they’re worse than the problems I’ve seen in the ICTR and the ICTY,” says Clair Duffy, who until January served as monitor of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal for the Open Society Justice Initiative headquartered in New York City. “That’s not to pretend that [the ICTR and ICTY] haven’t also had problems, but I think in terms of the independence of the court, the fact that they haven’t had Rwandan or Yugoslav judges—or, in the case of Sierra Leone, that the internationals had the balance of power—has meant that the credibility of the outcome in the court has withstood scrutiny more than the ECCC. And I think everything comes back to that.

“To me,” Duffy adds, “the quality of outcome is always judged against the quality of judicial independence in decision-making. You can’t look at the ECCC in a vacuum because it is in Cambodia, and in Cambodia the courts are used on a daily basis by the government to bring about political ends.”

By all accounts, Cambodia does not have a good track record when it comes to judicial independence. The U.N. special rapporteur for human rights in Cambodia, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and numerous domestic NGOs have for years pointed to the judiciary as one of the most problematic links in Cambodia’s legal system. “It’s weak, it’s very weak,” says Yeng Virak, the executive director of the Community Legal Education Center in Phnom Penh. “I don’t think we see the rule of law. Really, what we see in real life is the rank and file—the small guys—just execute the orders of their bosses without referring to the law, without even giving thought to the law, and whether the act is legal or illegal.”

Those characteristics of Cambodia’s domestic courts have a spillover effect on the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Virak says. “Of course we can see that there are negative influences of the Cambodian judicial system on the tribunal,” he says. “We cannot ensure the standard, the international standard. It’s a hybrid court, so you cannot expect much. You must lower your standards a bit. Of course, the U.N. brings a good image; they can be seen as the guarantor for the quality of the tribunal, its independence. But there are some nuances, some controversial issues that cause the court not to be fully independent and make meeting the international standard a bit difficult.”

Despite these concerns, some remain cautiously optimistic that the Khmer Rouge Tribunal will have a positive impact. “I see this as an opportunity to draw a lesson on genocide for the people of Cambodia,” says Chhang, whose research center is the tribunal’s primary source of documentary evidence. “We could have waited for a perfect trial, if there is one, but I doubt that would ever exist. But I do expect this problem. I think all of us involved in the negotiation, we kind of expected this.”

The tribunal is important for other reasons as well, Virak says. “One of the legacies that we want to see—besides the relative justice—is the good practices and capacity of the justice officers, of the lawyers, who are involved in that tribunal,” he says. “They can learn from the foreign justice officers, lawyers, prosecutors, judges and so on. They can learn the international standard, especially with respect to professional integrity and an independent judiciary. That’s what we wanted to see.”

Michael G. Karnavas, an American lawyer who has served as a defense counsel for both the Khmer Rouge Tribunal and the ICTY, puts it this way: “Here at the ICTY, legacy is what can we write in our positive outcomes. But legacy in Cambodia is something different. This is the very first time in modern Cambodia where they’re having a trial conducted like a trial. Where the parties are being treated more or less equally. Where there’s a debate on the issues.”

Prime Minister Hun Sen at an event this year marking the 34th anniversary of the downfall of the Khmer Rouge. Photo by Associated Press.

JUST ENOUGH JUSTICE

In addition to the tribunal’s makeup, another key issue for negotiators was just how many trials there should be. Yet again, political considerations came into play.

The final agreement between the Cambodian government and the U.N. designated two categories of possible defendants: first, senior leaders of Democratic Kampuchea (the name given to Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge); and, second, people believed to be most responsible for grave violations of national and international law in carrying out atrocities while the Khmer Rouge was in power.

Deciding just how many trials were necessary became a tough issue for the negotiators. They started with a list of about 30 possible trial defendants, says Scheffer, but that number now stands at between five and 10.

The Hun Sen regime wanted just enough trials to establish its own legitimacy. But the international community was looking for something more permanent from the process.

Through the tribunals, says Scheffer, “due process and investigative integrity also should be advanced. That builds capacity for the Cambodian justice system.”

Another consideration—this one practical rather than political—has been resources. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal has no guaranteed funding source from either the Cambodian government or the U.N. “That money has to be raised by voluntary contributions, primarily from governments,” says Scheffer, who has the primary task of doing the asking. Noting that the tribunals for Sierra Leone and Lebanon also are supported by voluntary funding, Scheffer says, “There’s tremendous fatigue on the part of governments that support them, but there was no other way to create them.” Right now, he notes, only enough money has been raised for the Khmer Rouge Tribunal to get it through the first quarter of this year.

The tribunal’s first case, against Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, operated as a trial run of sorts and went as smoothly as might be hoped for. The head of the notorious Tuol Sleng detention center, or S-21, Duch was directly responsible for the deaths of more than 12,000 inmates. A meticulous man with a staggering memory for details, the former math teacher kept highly precise records. Eased by Duch’s own confession, the endless records and testimony from the scant handful of those who made it out of Tuol Sleng alive, the case virtually sailed through. Duch was convicted in July 2010 of crimes against humanity and breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949. The trial chamber sentenced him to 35 years in prison, but the supreme court chamber later raised that to life in prison.

Case No. 002, however, is proving to be a tougher nut. Opening statements began on Nov. 21, 2011, and the trial is expected to run well into this year. The defendants, all octogenarians, held positions at the very top of the Khmer Rouge regime. Nuon Chea, known as Brother Number Two, was Pol Pot’s right-hand man and chief ideologue. Ieng Sary, a brother-in-law of Pol Pot, was foreign minister, while Khieu Samphan served as head of state. A fourth defendant, Sary’s wife, Ieng Thirith—the former minister of social affairs—was declared unfit to stand trial in September due to dementia.

Case 002 contains evidentiary complexities that didn’t exist in the case against Duch. But time also is becoming a factor. The trial chamber severed the indictment in hopes that at least one judgment would be reached before illness or death caught up with the defendants, but that order has been opposed by lawyers on both sides of the case.

Meanwhile, the outlook for cases 003 and 004 is even more uncertain. Initial investigations have begun, but so far no suspects have been formally identified. Moreover, the Cambodian government has made it clear that it prefers not to see any more cases go forward. Prime Minister Hun Sen even warned of possible civil war if the tribunal proceeds much further, and it’s a threat that resonates. The outlook for cases 003 and 004 also could be a cause of friction within the tribunal.

“People are afraid of war in this country. And it has been presented that cases 003 and 004 could cause problems with reconciliation now,” says Andrew T. Cayley, who serves as the U.N.’s co-prosecutor for the tribunal. “Whether or not that is the reality, the fact is that I’ve taken a position that I’ve got to follow the law and the rules. Whether or not [there have been] statements by the government there will be no more cases, they have to be legally determined.”

When the U.N.’s co-investigating judge resigned last year—the second international judge to quit that position in six months—he dropped a bombshell in the form of a 14-page memo alleging extensive efforts by both the Cambodian and U.N. sides to block his investigations into the politically sensitive cases 003 and 004. The bulk of his report focused on impediments that came at the orders of his Cambodian counterpart, which many viewed as further proof that the tribunal bends to pressure from the government.

“It’s not absolute justice, especially not after 30 years. It’s transitional justice,” says Virak. “You can’t get full justice. For example, there are many former Khmer Rouge cadre leaders who still go free, join certain positions. They’re not going to be prosecuted. We’re not going to get any statement, confession, apology so that you could learn from the past. Now people go free and the victim’s family sees that these guys are the ones who tortured my father, mother, sister, and still go free. And so people just say: Forgive and forget. We don’t want retributive justice. An eye for an eye, a life for a life—maybe instead we can forgive.”

And so the Khmer Rouge Tribunal stumbles toward an uncertain future. But while critics focus on its shortcomings, there also is hope that even flawed justice will be a step in the right direction. “We cannot avoid the politicization of the process—of course we cannot—but the overall outcome still remains satisfactory,” Vannath says. “People might argue over the results. Some might find them controversial. But the process itself, the effort itself, most people feel satisfied by that.”

Chea Vannath is the former president of the Center for Social Development, an NGO that promotes democratic values in Cambodia. Photo by Associated Press.

Abby Seiff is an American journalist in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, where she covers politics, foreign affairs and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal.