Results may vary in legal research databases

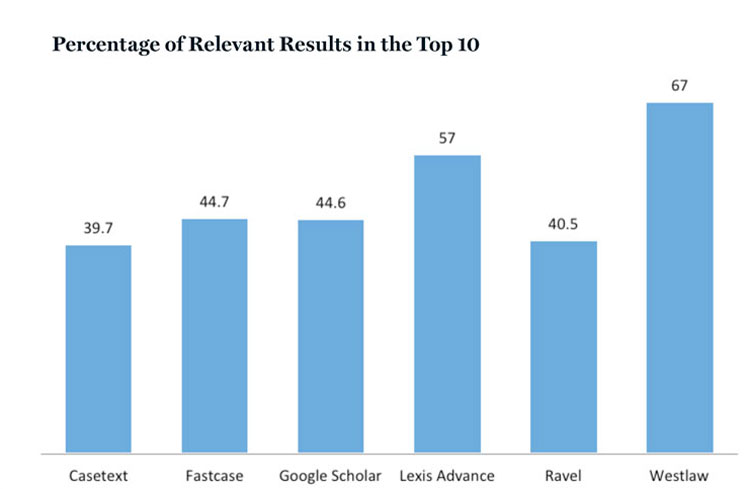

See the next chart, at the top of this page, “Percentage of Relevant Results in the Top 10,” which illustrates relevance in each of our six legal databases.

What is striking about this chart is how many results are not relevant. Even within 10 cases, not all of the results relate to the search terms. Westlaw (67 percent relevance) and Lexis Advance (57 percent relevance) performed the best. For Casetext, Fastcase, Google Scholar and Ravel (now owned by Lexis), an average of about 40 percent of the results were relevant. In terms of each database provider offering a different view of the same corpus of cases, how many of those relevant results were unique?

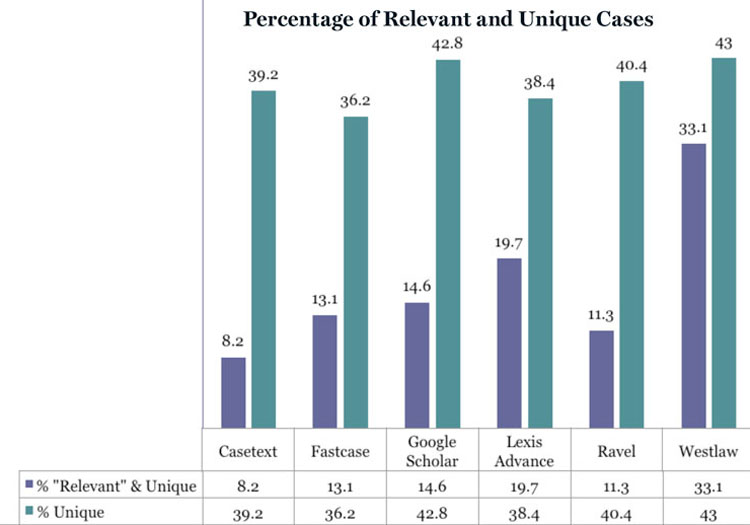

The final chart, below, “Percentage of Relevant and Unique Cases,” reflects how each database provider offers cases that are both unique and relevant in the top 10 results. Westlaw offers the highest percentage of such cases, at just over 33 percent. Lexis Advance has nearly 20 percent unique and relevant cases. Casetext, Fastcase, Google Scholar and Ravel have an average of 12 percent of relevant and unique cases. Of course, you don’t have to do the same search in all six databases to find all the relevant cases. All the cases are in all of the databases, and multiple searches may bring those unique and relevant results to the top.

The takeaway is that lazy searching will leave relevant results buried; if an important case is the 57th result from just one search, a researcher is not going to find it. Algorithms are just not going to do the heavy lifting in legal research. At least not yet.

OTHER DATA FROM THE STUDY

The study also looked at the age of cases that were returned in each search. Overall, the oldest cases dominated Google Scholar’s results. Almost 20 percent of the results from Google Scholar were from 1921 to 1978. The highest percentage (about 67 percent) of newer cases were returned by Fastcase and Westlaw. Ravel and Lexis Advance had an average of 56 percent newer cases.

Another area of diversity was the number of cases each database returned. The median number of cases returned in response to the same search varied from 1,000 for Lexis Advance to 70 for Fastcase. Casetext, Ravel and Westlaw each returned 180 results at the 50th percentile and Google Scholar returned 180. Each algorithm is set to determine what is responsive to the same search terms in vastly different ways.

For the most part, these algorithms are black boxes—you can see the input and the output. What happens in the middle is unknown, and users have no idea how the results are generated. While legal database providers tend to view their algorithms as trade secrets, they do give some hints in their promotional materials about how the algorithms work. A more detailed discussion of those materials (and other concepts in this article) is available in “The Algorithm as a Human Artifact: Implications for Legal (Re)Search” in the Law Library Journal. We need a frank discussion with database providers about what it means for a researcher to search in their databases and how researchers can become better searchers. Knowing that should not violate any trade secrets. Discussing algorithmic accountability with database providers can work, though proactive responses would be better. For example, I asked Lexis Advance about jurisdictional searching and they released a FAQ on the topic. No trade secrets were revealed, and researchers now have a better understanding of how to effectively search in Lexis Advance. Fastcase has responded to the discussions about algorithmic accountability by releasing an advanced search feature that lets the researcher adjust the relevance ranking for a specific search to privilege the attributes that researcher wants to emphasize. Algorithmic accountability is now open for discussion. Providing the kind of algorithmic accountability that enables researchers to create better searches should be a market imperative for all database providers, so please demand accountability.

As a matter of empirical fact, we now know some things about using legal databases that researchers had suspected but could not prove. We know that Westlaw and Lexis Advance return more relevant and unique results.

These databases have an edge: They’ve had decades to refine their strategies. Both have a large base of user information. Each has a detailed but different classification system and different sets of secondary sources. Recall that only 28 percent of the cases from Lexis Advance and Westlaw appear in both databases. It may not be so surprising that the results from Lexis and Westlaw are so different, as those results may differ in ways that conform to the respective worldviews encapsulated in their classification systems and the secondary sources their algorithms mine to return results.

This raises questions about two types of viewpoint discrimination that are worth exploring. The first is one familiar to all researchers: Authorial viewpoints are a form of viewpoint discrimination. Attorneys and librarians have always preferred, budgets allowing, to have more than one authorial viewpoint represented in their legal resources. What held true on the treatise level now holds true on the database level, and the differing worldviews of each database provider can be seen as a positive good.

The second kind of viewpoint discrimination results from the 19th-century viewpoint explicitly imported into Westlaw through its Key Number classification system and re-created in Lexis in its own classification system. Scholars have often pointed out that older and more established legal topics (think of contract rescission) fare better in these systems. Newer topics (which have changed over time, from civil rights in the 1960s and ’70s to cybersecurity today) are harder to fit into the existing schemes. So it is possible that searches in more established areas of the law will be more successful in these older databases.

If one is searching for solutions to legal problems in emerging areas of the law, it would be worthwhile to try the newer databases and see what their 40 percent of unique cases have to offer. The newer databases also offer new forms of serendipity: “summaries from subsequent cases” and the “black letter law” filters in Casetext, as well as citation visualizations in Ravel and Fastcase, are examples of new ways of adding value to the research process.

A FEW LAST WORDS

Researchers should take away a few key things from the study:

- Every algorithm is different.

- Every database has a point of view.

- The variability in search results requires researchers to go beyond keyword searching.

- Keyword searching is just one way to enter a research universe.

- Redundancy in searching is still of paramount importance.

- Terms and connectors searching is still a necessary research skill.

- Researchers need to demand algorithmic accountability. We are the market, and we can influence the product.

Algorithms are the black boxes that human researchers are navigating. Humans created those black box algorithms. We need better communication between these two sets of humans to facilitate access to the rich information residing in legal databases.

Clarification

Print and initial online versions of “Results May Vary,” March, should have noted that the data cited is from a 2015 study by author Susan Nevelow Mart. Algorithms and their results are continually changing, and each of the legal database providers in that study has changed their algorithms since the data was collected.

Susan Nevelow Mart is an associate professor and the director of the law library at the University of Colorado Law School in Boulder. This article was published in the March 2018 issue of the