Rebuilding Project

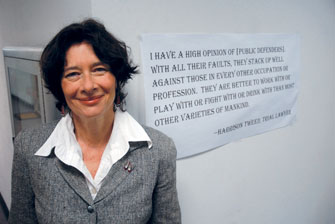

Denise LeBoeuf. (Photo by David Rae Morris)

Change is coming slowly to New Orleans’ infamous lower ninth ward since the waters receded after Hurricane Katrina touched land two years ago this month.

Houses still bear the spray-painted code of rescuers who went door to door in the weeks and months after the storm—first to search for victims and later to determine whether structures were safe for residents to return.

But here and there are bright, freshly painted homes. Outside is evidence of construction: lumber and shingles piled on the sagging brick sidewalks, the high-pitched whine of circular saws, the guttural exhale of pneumatic nail guns, and the whirring of cordless drills setting screw after screw into new drywall.

Up in the city’s Lakeview section, where modest shotgun shacks give way to more upscale brick and stone houses, the ratio is reversed; most of the homes have been or are being repaired. Only the occasional abandoned hulk with the unmistakable waterline just below its eaves sits waiting for a teardown crew to come around.

Along the canals, huge cranes work to rebuild the breached levees that let through the rushing waters, laying waste to so many New Orleanians’ little patches of home.

The collapse of most of the city’s infrastructure brought great loss; but it also brought opportunity. The city is at the brink of serious progress with a chance to rebuild entrenched systems nearly from scratch—if only all the players can agree on how best to do so.

Few things in New Orleans show the line between old and new more starkly than the criminal justice system, once an archaic relic of the Old South, now being reborn slowly and painfully into something resembling the rest of 21st century America.

Out at the intersection of Tulane and Broad, beyond the Central Business District, the criminal courts of Orleans Parish have finally settled back into their rehabbed courthouse, after a year of wandering the city like nomads, borrowing space everywhere they could—from the local federal court to the New Orleans Bar Association offices.

Across the street, the public defender’s staff has its own office space for the first time in its history. The leased space in the Tulane Towers office building is drab and shabby, but it feels like luxury accommodations to the new full-time staff.

“We even have a conference room for staff meetings and training,” says Chief Defender Christine Lehmann, a mixed note of pride and wonder in her voice.

But the post-Katrina reforms may be more far-reaching than just office space. The Louisiana legislature has spent its summer attempting to craft the state’s first independent board to oversee the indigent defense system. As part of a proposed overhaul of the state’s public defender system, a state public defender board would ensure that the 80 percent of criminal defendants in Louisiana who require an appointed lawyer are able to obtain one. As of early July, a bill revamping the system was awaiting Gov. Kathleen Blanco’s signature. The bill includes $27 million in statewide funding.

LONG OVERDUE OVERHAUL

This represents a sea change for the bayou state. Portrayed as palpably unfair and chronically inefficient in study after study, Louisiana’s legal system all but disintegrated in the wake of Katrina. And longtime critics of the system say lawmakers have seized the opportunity to remake representation for the state’s indigent defendants from the ground up.

“We have to do this. The time has finally come, and not doing it now would be hard to justify to the public,” says Denise LeBoeuf, former chair of the New Orleans Indigent Defense Board.

Complaints about the system are nothing new. For several decades, studies by entities as diverse as the ABA, the American Civil Liberties Union and the U.S. Justice Department have characterized Louisiana’s indigent defense system as substandard to the point of being unconstitutional.

Perhaps because of its inefficiencies—made worse still by the widespread loss of records as the result of Katrina—hard statistical evidence can be tough to come by. In 1998, in one of the few statistical categories reported to the National Center for State Courts, Louisiana recorded the highest number of new criminal case filings per capita of any system in the nation.

Despite Hurricane Katrina, that trend has continued, say critics, with disastrous results for those too poor to hire their own lawyer.

It takes too long after an arrest, say critics, to be charged with a crime; too long to be appointed a lawyer; too long for a case to come to trial; and too long to be convicted or exonerated.

Caseloads for public defenders are improving, but are still far below national standards. The courts themselves are unevenly administered and riddled with politics and patronage.

One report, compiled after Katrina by the National Legal Aid and Defender Association, attempted to chronicle those problems anecdotally. The New Orleans criminal justice system, it concluded, had “long-standing, pre-existing systemic deficiencies that were unmasked and accentuated” by the storm.

That report—presented as a “strategic plan” by NLADA, an organization of publicly paid criminal defense attorneys headquartered in Washington, D.C.—has become the centerpiece of state legislative efforts to reform the system.

The report describes an indigent defense system built on patronage and financed by traffic tickets—a system that has historically fallen short of nearly every national standard for fairness and efficiency set by the ABA. And after Katrina, things only got worse.

A shortage of funds forced Orleans Parish to fire 34 of its 41 part-time attorneys. Remaining public defenders saw their caseloads swell by as much as eight times the national standard. Court dockets became so jammed with indigent defendants, said the report, that two judges—including the presiding criminal court judge—closed their courts to defendants without lawyers.

“If not for Katrina, this [current move to reform] wouldn’t have happened,” says Arthur L. Hunter Jr., a criminal court judge in Orleans Parish. “At least not right now.”

Even the first, modest reforms didn’t come easy. Earlier this year, LeBoeuf and three other members of the Indigent Defense Board were removed by a group of influential Orleans Parish judges who appointed them. The judges complained that the indigent defense system they had been accustomed to was changing at too rapid a pace. The board has challenged the action in federal court.

Several key judges named in the lawsuit declined to return phone calls requesting comment.

Hunter, who was not among them, says the judges were simply protecting their prerogatives under the status quo. “A lot of that was just about patronage and the good ol’ boy network,” he adds.

JAMMED CASELOADS

One of the historical concerns among critics of the Louisiana justice system has been the human cost of its seeming inefficiency, especially on the working poor. With courts, prosecutors and public defenders carrying high—in some cases astronomical—caseloads, even those who have been neither charged nor convicted have too often languished in New Orleans’ jails.

At the time of Katrina’s landfall, more than 6,500 detainees had to be evacuated from New Orleans’ Old Parish Prison complex. Prisoners were first herded to a highway overpass, then allocated to any jail in the state that would take them—with little or no distinction made between pretrial detainees, violent offenders and those who were serving short sentences for convictions for minor crimes.

But symptomatic of the historical problem, said NLADA researchers, is the fact that there were 6,500 prisoners in need of evacuation in the first place. Their study pointed to several systemic flaws.

First, under Louisiana law, even those arrested for misdemeanor offenses can be held without formal charges for 45 days. Those arrested on felony complaints can be detained without charges for 60 days.

Under that system, said the NLADA report, justice delayed is commonplace.

As a matter of routine, police investigating crimes feel no pressure to provide prosecutors with basic case evidence until the 45-60 day limit is set to expire. Cases based on thin or nonexistent evidence receive the same priority as cases with solid charges.

Moreover, NLADA reported, indigents arrested were often assigned representation on an equally timely basis: “In Orleans Parish, the opposite of prompt appointment of counsel occurs routinely—representation by the public defender office is structured to discourage early client contact, avoid initial scrutiny of evidence and/or eliminate virtually any action that could result in a speedy disposition of the charges.”

New Orleans District Attorney Eddie J. Jordan Jr. has acknowledged that at least a third of such cases are dismissed without prosecution. And those without the funds to make bail are forced to stay in jail whether there is actual evidence against them or not.

Still, Jordan says he believes that few who plead to charges in order to get out of jail are really innocent.

“I think those who say that are out of touch with reality. I think defendants plead guilty because they are guilty. We simply have a large number of recidivists in New Orleans,” says Jordan.

Dane S. Ciolino, a law professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law and one of the four board members dismissed by the Orleans Parish judges earlier this year, says as many as half of all arrestees in New Orleans are never charged with a crime but still spend the full 45-60 days in jail. He also thinks that many actual criminals drop through that crack.

“Of course, it stands to reason that if you’re releasing innocent people while looking for evidence, you’re probably releasing some bad guys, too,” Ciolino says.

Some of those releases can be attributed to the city’s shorthanded police department. Many former New Orleans officers left the city along with as much as two-thirds of the population, says Ciolino. And those who remain are still working from temporary trailers because the main police station has yet to be repaired or replaced.

Even if those arrested were charged, the system that represented them was historically suspect as under-manned, underfunded, and subject to pressure and political manipulation because of systemic flaws. For instance, indigent defense in most Louisiana parishes traditionally has been funded by revenues from fines and traffic tickets. If revenues fall short of projections, as they have in New Orleans since so many people left after Katrina, budgets are summarily slashed.

In 2005, according to New Orleans CityBusiness, about 75 percent of the $2.2 million budget for public defenders in New Orleans was produced by traffic fines. The rest of the budget, about $550,000, was provided by the state.

By contrast, the Department of Justice says it will take more than $8.2 million per year to bring the New Orleans public defender system up to national standards.

There was also a problem of local political control. The indigent defense board of each parish was appointed by local judges. And in New Orleans, judges had the power to hand-pick which defense lawyers would be assigned to their courtrooms.

“Think about that. It’s like the referee getting to tell the coach who to play and at what position. The judges shouldn’t be involved in that,” LeBoeuf says.

The practice of supplementing public defenders with court-appointed private lawyers—which has been successful in some less populous parts of the state—also hasn’t worked well in New Orleans. When scarce available funds are divided by the number of eligible defendants, the hourly rates paid to private attorneys are far below what lawyers make from their private legal work.

Before changes made last year by the Indigent Defense Board under LeBoeuf, lawyers almost never met with their clients or witnesses outside of court. Public defenders were mostly part-time private lawyers, and the only office space to speak of was a few shared desks in a corner of the courthouse. There was nowhere to meet with clients, nowhere to store files—not even a telephone number.

Most publicly appointed defense lawyers met their clients when they were brought into the courtroom from the holding cell for their first appearance.

If a defendant claimed an alibi or other extenuating circumstances, all his or her lawyer could do most often was to advise the client to make sure that witnesses appeared at the next scheduled court date. Too often, this meant that defendants had to try to track down their own witnesses while in jail.

Public defenders, like their prosecutorial counterparts, were assigned not to specific cases but to particular judges’ courtrooms. Each lawyer went to the same courtroom every day and took on whatever cases were assigned to that judge that day. If a defendant had separate cases pending before two judges, chances are he or she had different lawyers for each case as well.

“The old way was dedicated to the process of moving cases. The system needed to be made client-oriented,” says LeBoeuf.

It is a system that made—and still makes—the pressure to seek a plea bargain overwhelming. Too often, defenders were forced to cut plea deals based on the information in police reports. Actual guilt, innocence or extenuating circumstances simply fell by the wayside, critics say.

And that would be troubling enough, Lehmann says, but when coupled with Louisiana’s harsh multiple-offender statutes, such pleas to time served often meant that by the time someone was arrested for the second or third time, that person was facing a mandatory sentence of 10 years or more in state prison.

Often, young men, mostly black, were sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola with a record consisting of nothing more serious than assault or drug possession, LeBoeuf says.

“At least some of these guys are probably guilty of little more than not running faster when the police showed up” in some of the city’s most crime-infested neighborhoods, says LeBoeuf.

Underlying all this has been an attitude toward criminal defendants in general—and New Orleans in particular—that permeates the system.

“In Louisiana, providing lawyers for defendants is considered a perk. There’s an assumption that if someone is arrested, he must be guilty,” says LeBoeuf. “So why should the state pay a lawyer to try to ‘get him off?’ ”

The answer, of course, is because the Constitution says so. In 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court said that criminal defendants whose liberty is at stake have a right to qualified defense counsel. Those who cannot afford to hire an attorney are entitled to have one provided free of charge by the state, said the court. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335.

Moreover, in Louisiana there is a great divide between New Orleans and the rest of the state. To many from rural areas and smaller towns, the idea of sharing state tax dollars with the City of New Orleans is so galling as to seem almost sinful.

SMALL CHANGE, BIG CHANGE

Still, attitudes are changing—at least in the state legislature. Taking to heart many of the recommendations by NLADA, the indigent defense system is undergoing, many hope, a post-Katrina restructuring that will include a transformation of public defenders from part time to full time, acceptable caseload standards and the development of a professional budget.

Much of this would be overseen by a centralized agency that would initiate binding standards for attorney workloads, qualifications and performance. The agency would be supported by a statewide funding system to make up any shortfall between projected revenues and actual collected funds in any given year.

The New Orleans Bar Association lobbied heavily for the bill, and its supporters are confident that a full and adequately funded system will be approved.

Meanwhile, the New Orleans Indigent Defense Board hasn’t been idle. After Katrina, advocates for reform, including LeBoeuf, saw a chance to fix a few of the system’s obvious flaws. After widespread resignations, LeBoeuf and four other new members were nominated by the New Orleans Bar Association and the Greater New Orleans Louis A. Martinet Legal Society, whose membership is primarily black.

LeBoeuf was elected chairwoman of the new eight-member board, which began service in April 2006.

One of the board’s first moves was to rent office space for the public defender staff and hire full-time lawyers. It also assigned each case to a particular lawyer, creating a link between the client and the lawyer.

Now, because lawyers get case files ahead of time, they can visit clients at the jail or have family members come to the office with documents or other evidence to help the client’s case.

JUDGES REBEL

The new system is not without its flaws, LeBoeuf admits. Many judges complain that their dockets move much more slowly. Before, when each judge had one or two part-time defenders assigned to his or her court, lawyers on both sides knew the judge’s preferred way of doing things, and cases moved quickly.

Now, a new lawyer appears for each new defendant, bogging things down. The slowdown not only made the courts more sluggish, the judges told the board, but worked to the detriment of defendants as well.

“I had judges saying, ‘My old P.D. would have known what motion to make to get the guy released. The new lawyer doesn’t know how things work in my courtroom and the case gets continued for further investigation, and the guy goes back to jail to wait it out,’ ” says LeBoeuf.

Moreover, some of the attorneys preferred the older system of compensation, which allowed them to keep their private practice. When long-term part-time defenders were given the option of jettisoning their private practices to work full time for the public defender’s office, some howled. Some had become comfortable balancing part-time public defense work with private practice, LeBoeuf says.

There is also the continuing problem of staffing. Where national caseload standards suggest a minimum of 75 public defenders for the New Orleans office, the staff is currently about half that, says Lehmann. And as always, money for the new office has been tight.

In defending the state’s status quo, some judges felt it was a waste of the defense system’s fragile resources to pay for office space, training, salaries and benefits for full-time lawyers. And tensions between those judges and public defenders came to a head in March and April.

The public defender’s office notified some judges that it would not accept new clients from their courts because a surge in new clients exposed the office to potential charges of ineffective counsel.

While a few of his peers set forth to fire LeBoeuf and her colleagues on the Indigent Defense Board, Hunter threatened to hold the public defender in contempt and actually released some defendants from custody when the defender’s office failed to send lawyers to his courtroom. The judge said he was just trying to get the state legislature’s attention. “The legislature has a constitutional responsibility to provide funding for indigent defense in Louisiana,” he notes.

The executive director of the New Orleans Bar Association, Helena Henderson, is hopeful that the reforms developed by the state legislature will make moot the board’s federal lawsuit and the tensions behind it.

“I hope that relationships can begin to be healed, and the discord between the public defenders and the courts will finally be quieted,” says Henderson. “It’s not too late for justice in New Orleans.”

LINKS

Studies of Louisiana’s criminal courts.

Legislation that creates the Louisiana Public Defender Board and provides with respect to the delivery of public defender services in the state of Louisiana.

Sidebar

Dysfunctional Defense

When the New Orleans Bar Association asked for civil lawyers to take on some criminal clients to help ease the caseload, Carmelite Bertaut stepped up. She was, after all, the president of the New Orleans bar at that time, in early 2006. She wanted to lead by example, and she wanted to help her beloved hometown recover from Hurricane Katrina.

She is a partner at one of the Crescent City’s most prestigious law firms, Stone Pigman Walther Wittmann, and is known as a tough litigator who handles class actions, complex commercial litigation and products liability cases.

She is, in short, no wallflower. She thought she was ready for anything. So she volunteered to take on an indigent criminal case.

It was in April 2006, weeks after her client’s first court appearance, that Bertaut recalls being handed the thin case file of a young man who was arrested on New Year’s Day, more than three months earlier, for allegedly hitting another reveler with a beer bottle in a Bourbon Street bar.

The Orleans Parish district attorney’s office declined to discuss the evidence specifically, but according to Bertaut, police reports alleged that the victim received a single stitch on the back of his scalp and was released from the hospital. And though the victim did not see his attacker, he fingered Bertaut’s client based on an argument with the client earlier that evening. The client—for whom she requested anonymity—denied having hit the victim. Few other witness statements were recorded, and none of the witnesses could be found.

By the time Bertaut met the client in court, he had already been behind bars for nearly four months. He was charged with aggravated assault, simple assault and shoplifting. It was unclear exactly what the client was alleged to have stolen,

Bertaut says, but it may have been the beer he was drinking at the time of his arrest. His bail, according to court records, was set at $50,000.

The client was a 19-year-old laborer from Atlanta who had come to New Orleans just a month or two earlier to work construction on post-Katrina rebuilding sites. He had no prior arrest history in New Orleans or his hometown, says Bertaut.

Neither he nor his parents—a mother in Atlanta, a father in Baltimore—could afford the bail bond.

When Bertaut got the case, the police officers who made the arrest on New Year’s Day no longer worked for the New Orleans Police Department, and Bertaut could not locate them. She was told by their former colleagues that both might have left New Orleans, and no one seemed to know where to find them.

Shortly after meeting with her client, according to court records, Bertaut filed motions for a reduction in bond and a speedy trial. But because the courts were in chaos due to the destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina, her motions were repeatedly rescheduled.

Meanwhile, her client remained in jail.

By the end of May, she was still filing motions—this time to modify his bail and to conduct a preliminary examination.

These, too, were postponed by the court for one reason or another.

In June—five months after the original arrest—Bertaut filed a motion to show cause as to why the charges should not be dismissed for lack of evidence.

At a hearing on the motion, the judge listened to Bertaut’s plea on behalf of her client: The charges were unclear, with nothing to support the victim’s statement; the injury was minor; her client had no prior run-ins with the law; if he hadn’t paid for his beer, it was only because the police took him away before he had the chance.

The judge congratulated Bertaut on how well she represented her client. He acknowledged her pro bono service and said he respected her firm for donating so much time and so many resources to the case.

He dismissed the shoplifting charge, but refused to dismiss the assault charges. The assistant district attorney offered a deal: Plead guilty to one felony count of assault and accept a sentence of three-and-a-half years, with credit for time served.

Bertaut was incredulous.

“Three-and-a-half years and a lifelong felony record for a bar fight where there were no real injuries and they couldn’t even prove my client was the bad guy? I thought, ‘No way. This isn’t right.’ ”

By this time, Bertaut’s client had been in jail for five months. He was gaunt and tired, she says. He was desperate for some certainty about when he would be released. If he lost at trial, he was facing 10 years in state prison.

Bertaut took the client to an empty room in the courthouse and let him use her cell phone to call his parents.

“He was crying, the parents were crying, I was crying, my associate was crying, my assistant was crying. It was a mess. I can’t remember ever feeling so helpless,” Bertaut says.

Bertaut called a colleague with experience in criminal law. “Take the deal,” he told her. “It’s a good deal—as good as you’re going to get.”

The client took the deal. He is now serving time in a Louisiana state prison.

It’s an experience, Bertaut says, that she is not eager to repeat.

But the district attorney’s office sees no problem with the outcome of the case.

“If she believed her client was not guilty, she had an ethical obligation to go to trial,” says First Assistant District Attorney Gaynell Williams.

“It sounds to me like the client made an informed decision and decided to plead guilty,” Williams says.