Psychedelic Rx: Legal battles aim to expand patients' access to psilocybin and other hallucinogens

Photo by Shutterstock.

In March 2020, as people around the world felt increasing fear and uncertainty over COVID-19, Erinn Baldeschwiler suffered a devastating blow. The 48-year-old mother of two teenagers from North Bend, Washington, felt a lump on her chest and soon discovered she had stage 4 metastatic breast cancer. Tumors had spread throughout her body, including to her lymph nodes, adrenal glands and bones, and she received sobering news that she might live for only two more years.

For the rest of her limited time, Baldeschwiler wanted the best possible quality of life. She chose immunotherapy over chemotherapy and its debilitating side effects. She also asked doctors at the Advanced Integrative Medical Science Institute, an oncology clinic in Seattle, for help with the severe anxiety and depression that came with knowing she wouldn’t watch her children grow up.

After consulting Dr. Sunil Aggarwal, her palliative care physician and the co-director of the AIMS Institute, Baldeschwiler began ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. In two separate sessions, a therapist brought her into a dimly lit treatment room. She put on eyeshades, listened to relaxing music and received an intramuscular injection of ketamine, an anesthetic drug that can facilitate therapeutic trances and help ease existential distress.

After each session, Baldeschwiler met again with the therapist to process her experience, which she describes as helping her develop an inner sense of peace.

“I am not against modern medicine, because it has kept me alive for the last couple of years. But we’re multifaceted, multidimensional beings,” Baldeschwiler says. “This is really diving into the whole emotional side and finding mental clarity and spiritual ease around everything, because life will throw you a lot of things that you have to manage, like a death diagnosis.”

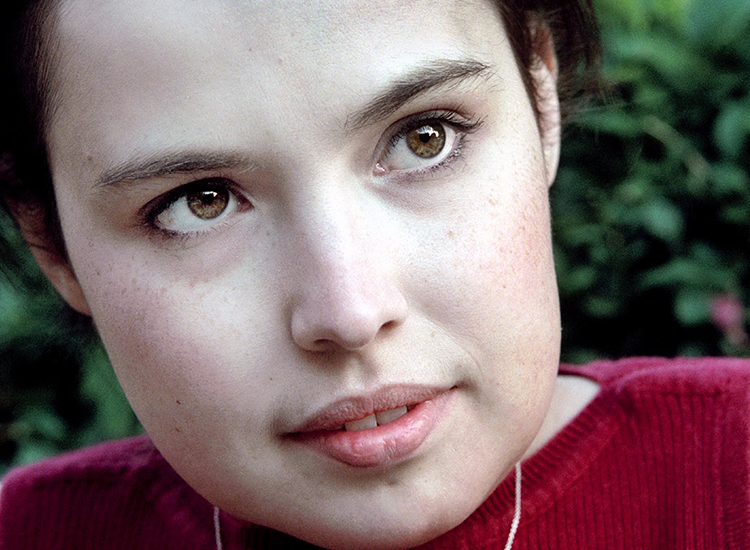

Erinn Baldeschwiler wants to incorporate psilocybin, the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms, into her medical treatment. (Photo by Yosef Kalinko/ABA Journal)

Erinn Baldeschwiler wants to incorporate psilocybin, the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms, into her medical treatment. (Photo by Yosef Kalinko/ABA Journal)

While Indigenous communities have long integrated plant-based psychedelics such as peyote and ayahuasca into their spiritual practices, interest in using both natural and synthetic hallucinogenic substances to alleviate depression and anxiety as well as anorexia, substance use disorder and other mental health conditions has increased in recent decades.

Scientific studies pointing to psychedelics’ benefits, which include euphoria and profound shifts in perception, as well as journalist Michael Pollan’s 2018 bestseller, How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression and Transcendence, helped fuel this enthusiasm. The legal landscape is also changing as more jurisdictions aim to decriminalize or even regulate the use of psychedelics.

Baldeschwiler and other patients have been particularly drawn to the idea of incorporating psilocybin, the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms, into their medical treatment.

In 2018 and 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration designated psilocybin therapy, which is currently being studied in clinical trials, as a “breakthrough therapy” for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder.

“I have always been very much interested in other avenues of treating whatever pain and suffering we might have as opposed to just taking a pill,” says Baldeschwiler, who talked to Aggarwal about using psilocybin in her own therapy. “I don’t want to take an antidepressant drug if there is an alternative, and especially if there is a natural alternative.”

While federal and Washington state “Right to Try” laws allow terminally ill patients to access certain investigational treatments, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in February 2021 prevented Aggarwal from obtaining psilocybin for his patients. This led to a legal battle that Baldeschwiler says is wasting her and her peers’ precious time.

“If there is something out there that can safely help us move through this transition to death and find a sense of peace and calm in making that transition, then by all means we should have that option,” Baldeschwiler says.

Fight to try

In 2012, Aggarwal became involved with the New York University Psilocybin Cancer Project and its research into how psilocybin affects anxiety and psychosocial distress in advanced cancer patients.

Dr. Sunil Aggarwal challenged the DEA in court, asking to use psilocybin to treat his patients.

Dr. Sunil Aggarwal challenged the DEA in court, asking to use psilocybin to treat his patients.An NYU study was published four years later, showing not only substantial improvements in anxiety and depression among participants but also decreases in their feelings of hopelessness and increases in their spiritual well-being. More than six months after receiving psilocybin, up to 80% reported lasting reductions in anxiety and depression.

After co-founding the AIMS Institute in 2018, Aggarwal wanted to try psilocybin-assisted therapy with Baldeschwiler and Michal Bloom, a retired Department of Justice attorney with advanced ovarian cancer.

“These are patients who are having a significant psychospiritual burden of illness and depression and anxiety associated with that,” Aggarwal says. “They both utilize ketamine therapy, but we wanted to try psilocybin therapy and hope it can have a powerful effect to help palliate some of their emotional and spiritual distress.”

Because the Controlled Substances Act placed psilocybin in Schedule I in 1970, no distributor would provide the drug to Aggarwal without the DEA’s permission. Schedule I drugs, which also include heroin and marijuana, are thought to have no FDA-approved medical use and a high potential for abuse.

Some in the medical field also worry that most studies of psychedelics have been conducted with small groups of people who were prescreened for certain underlying conditions. Dr. Michael Bogenschutz, a psychiatry professor who directs the NYU Langone Center for Psychedelic Medicine, told the New York Times last year that this makes it difficult to determine whether those who take the drugs without supervision will have adverse reactions.

Aggarwal began working with Kathryn Tucker, special counsel and co-chair of the Psychedelic Practice Group at Emerge Law Group in Seattle. In January 2021, Tucker asked the DEA to give Aggarwal guidance on how to order psilocybin for therapeutic treatment.

Despite Tucker’s argument that psilocybin met the requirements under the federal and Washington state Right to Try laws, the DEA said in its response a month later that it could not fulfill Aggarwal’s request. The DEA told Tucker that “absent an explicit statutory exemption to the Controlled Substances Act,” it had no authority to waive the law’s requirements. The federal agency suggested instead that Aggarwal apply to be a Schedule I researcher.

The DEA did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Tucker and her co-counsel took the matter to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at San Francisco in March 2021. They attracted amicus support from multiple groups, including a coalition of attorneys general from eight states and Washington, D.C., who said they had “an interest in avoiding undue federal regulation, particularly criminalization, of the practice of medicine.”

“My goal with this case is to compel acknowledgment by the DEA that Right to Try is the law of the land, and the DEA must find a way to accommodate it,” Tucker says.

The 9th Circuit heard arguments in September 2021 and dismissed the case Jan. 31. The court said it lacked jurisdiction to review the DEA’s response, which was an informal letter and not a final agency action.

“I’m a bit disheartened that we waited nearly five months, and after five months, it feels like they took a legal technicality approach to dismiss us,” Aggarwal says. “They didn’t even want to consider the heart of the issue—that these people are dying, need a solution, and Right to Try seemed like the right one.”

Forward movement

Abigail Burroughs died in 2001 at the age of 21. (Photo by Bill O’Leary/The The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Abigail Burroughs died in 2001 at the age of 21. (Photo by Bill O’Leary/The The Washington Post via Getty Images)The case of Abigail Burroughs, a Virginia teenager who battled head and neck cancer, was influential in the Right to Try movement.

After a year of treatment, Burroughs’ condition hadn’t improved. Her oncologist suggested she take an experimental drug, but the FDA denied her request to access it through a “compassionate use” program. She became too ill to participate in a different clinical trial and died at age 21 in June 2001.

Her father created the Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs and sued the FDA, arguing that terminally ill patients without treatment options have a constitutional right to try drugs that are shown to be sufficiently safe in clinical trials.

The district court dismissed the suit. But in May 2006, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit reversed the dismissal and remanded the case to the district court.

The FDA successfully petitioned for an en banc hearing, and the full D.C. Circuit vacated the earlier panel’s decision, finding there was “no fundamental right ‘deeply rooted in this nation’s history and tradition’ of access to experimental drugs for the terminally ill.”

But the en banc panel noted that “the alliance’s arguments about morality, quality of life and acceptable levels of medical risk are certainly ones that can be aired in the democratic branches.”

Christina Sandefur, the executive vice president at the Goldwater Institute, a free-market public policy organization in Phoenix, developed an interest in advancing health care freedom and took the appellate court up on its offer: She began working on a model Right to Try bill to share with state lawmakers and patient advocates.

“There had been no movement at the federal level for decades,” Sandefur says. “We thought what we needed to do was get reform in a place that was closer to the people and show this is truly something that patients want and need all over the country.”

Colorado became the first state to adopt a Right to Try law in 2014, and according to the Goldwater Institute, 40 other states enacted similar statutes within the next four years. In May 2018, Congress passed federal legislation that recognizes the right of terminally ill patients to access investigational treatments.

“It’s something that literally touches everyone,” says Sandefur, who also helped draft an amicus brief in the AIMS Institute’s case. “Everyone knows someone they’ve had to say goodbye to early because they faced a terminal illness, and there is this innate sense of anger and frustration with a system that is outdated.”

Matthew Zorn, a partner in Yetter Coleman’s Houston office, also found the AIMS Institute’s case raises profound policy questions, including whether the medical system benefits individuals with terminal illnesses.

Zorn began focusing on regulatory and constitutional issues involving controlled substances in 2019, and he later joined Tucker in representing Aggarwal and his patients.

“There is a perception—and, frankly, it is very hard to battle against it—that drugs are bad,” Zorn says. “Anytime you’re dealing with that in a case, and you’re walking into federal court, you’re running uphill on an incline.”

Zorn hoped to help draw attention to the more complicated narrative, one in which dying patients are in a different place than most when evaluating the risks and benefits of treatments. Despite the case’s outcome, he doesn’t regret raising the profile of the issue.

“What brought me into this space and what keeps me here is the very people who need this most are not being served by their government right now,” Zorn says.

Shifting psychedelics policy

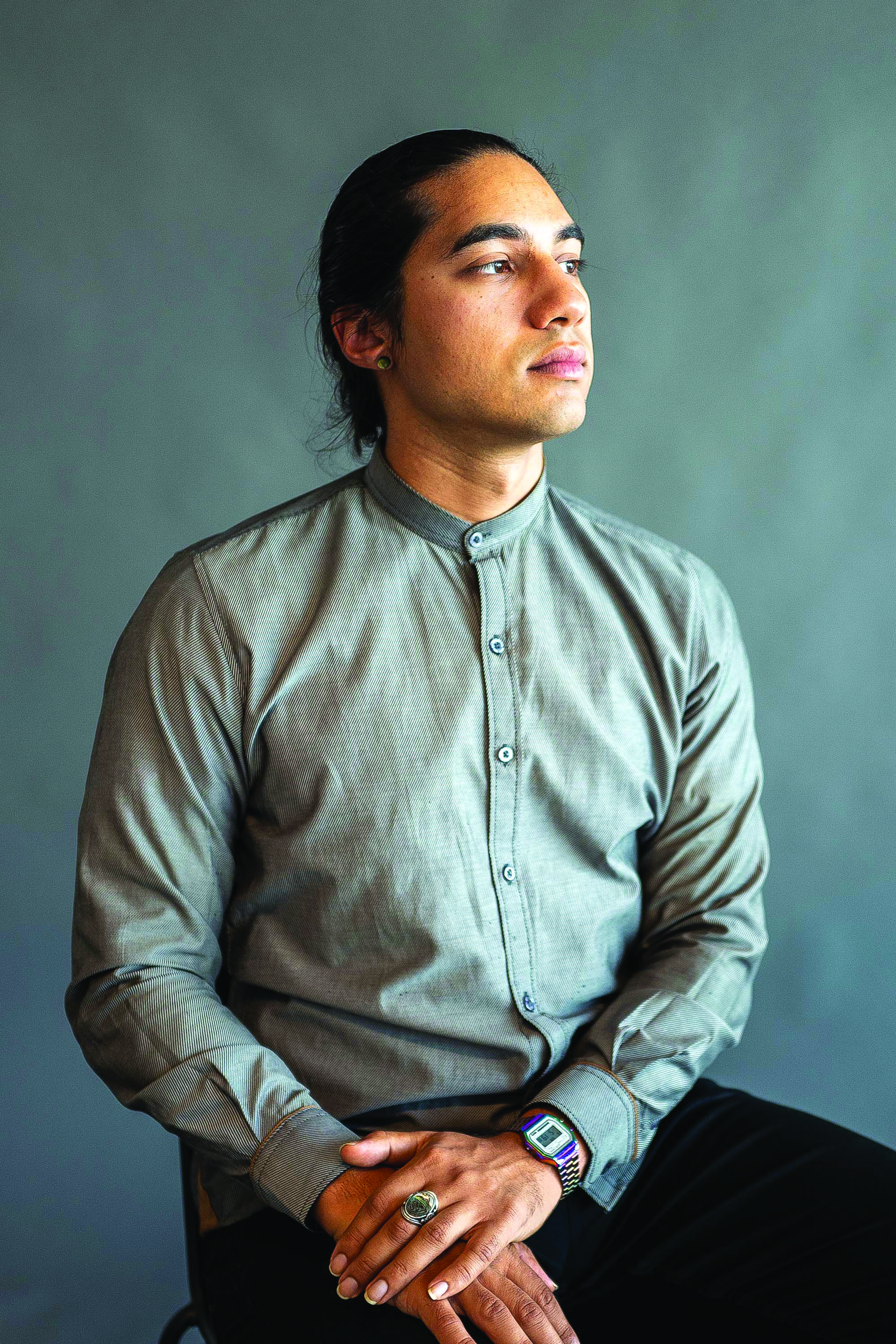

Ismail Ali is MAPS’ director of policy and advocacy. (Photo by Maximillian Rainey)

Ismail Ali is MAPS’ director of policy and advocacy. (Photo by Maximillian Rainey)Ismail Ali’s work with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies includes promoting reforms that permit the safe use of psychedelics.

He explains that the San Jose, California-based nonprofit research organization opened after the DEA added MDMA, the active ingredient in ecstasy, to Schedule I in 1985. The drug joined LSD and other psychedelics, which were studied extensively by scientists and psychotherapists through the 1960s but deemed dangerous by the federal government after the counterculture embraced them for recreational purposes.

Despite reports of their adverse effects, which included “bad trips” and suicide, advocates called for more research into psychedelics for medical treatment.

After studying the use of MDMA with therapy for PTSD, MAPS in 2016 released Phase II clinical trial results showing two to three sessions improved participants’ conditions. It could receive FDA approval for the first psychedelic-assisted therapy as early as 2023.

“There was a sense that if we could get the science right, we could prove that the policy as it currently operates is not working the way we want it to, not only because it doesn’t deter drug use, but it doesn’t keep people safer,” says Ali, MAPS’ director of policy and advocacy.

Those plans have come to fruition as cities and states are expanding access to psychedelics. In May 2019, Denver became the first city to decriminalize the personal use and possession of hallucinogenic mushrooms. Oakland and Santa Cruz in California; Somerville and Cambridge in Massachusetts; and Washington, D.C., followed with measures making arrests for the use or possession of natural psychedelics the lowest priority for law enforcement.

In November 2020, Oregon voters approved a ballot initiative that would legalize the use of psilocybin for mental health treatment in supervised settings. The Oregon Psilocybin Services Section is now creating the country’s first regulatory framework for psilocybin services. It will begin accepting applications for licensure in January 2023.

“With psychedelic policy so far, it was 20 years or 30 years of just research, and now you have all these approaches happening simultaneously,” says Ali, who serves on the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board’s Equity Subcommittee. “There has been a huge increase in the size and the breadth of the movement to change policy.”

Researchers with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies have been conducting clinical trials of psychedelic-assisted therapy. (Photo courtesy of MAPS)

Researchers with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies have been conducting clinical trials of psychedelic-assisted therapy. (Photo courtesy of MAPS)

Advocates in other states are also working to shift their psychedelics policy. Lawmakers introduced a proposal in Washington in January that was based on Oregon’s legislation. It would have allowed the state’s health department to regulate psilocybin so adults could use it in controlled settings, but it failed to pass.

The California state Senate passed a bill last year to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of seven psychedelic substances, including psilocybin, LSD and MDMA. It awaits the Assembly’s consideration.

And in Colorado, voters could see a ballot initiative in November that would decriminalize the use of psilocybin and other natural psychedelics and create regulated access to these substances for mental health treatment for adults. A separate measure could allow adults to use or possess natural psychedelics.

Lessons from cannabis

(Photo from Shutterstock.

(Photo from Shutterstock.For lawyers looking to understand the evolving psychedelics environment, a lot can be learned from the growth of the cannabis industry, says Vincent Sliwoski, the managing partner of Harris Bricken Sliwoski and editor of its Canna Law Blog and Psychedelics Law Blog.

As a business lawyer in Portland, Oregon, he began advising cannabis clients in 2010, when there was only a state statute permitting people with certain medical conditions to grow marijuana or ask someone to do it for them.

However, Sliwoski says, as companies began to interpret the statute liberally and create their own retail market for medical cannabis, the Oregon legislature moved to implement regulations. State lawmakers approved a medical marijuana dispensary registry system in 2012, and voters decided to legalize recreational marijuana in 2014.

Sliwoski says other states followed a similar model. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 37 states and Washington, D.C., permit the medical use of cannabis. Nineteen states and the nation’s capital have legalized its recreational use.

“I think because people saw cannabis roll out without all of these ill effects and ill societal effects that prohibitionists have been predicting, it makes it a little easier for psychedelics, other Schedule I drugs, to follow along,” Sliwoski says. “There is a model for states now regulating something that is a Schedule I substance under federal law.”

Sliwoski points to differences between the drugs that could make the path easier for psychedelics. While the cannabis industry evolved in stages, people in states like Oregon have shown a desire to move directly into regulating the use of psychedelics. He adds that several law firms have created psychedelics practices despite questions around whether lawyers can advise clients on activities that are illegal under federal law.

“There is a sea change, like in the zeitgeist, at a really fast pace that we didn’t see with cannabis,” he says.

A national Psychedelic Bar Association launched in 2021 to connect attorneys who want to explore novel legal and policy issues involving psychedelics. Ali and Tucker were involved in its creation, and Zorn became an early member.

Graham Pechenik, a patent attorney and the founder of Calyx Law in San Francisco, is also a member of the PBA. He initially worked with cannabis entrepreneurs but began assisting startups and venture capital firms that showed increasing interest in psychedelics in late 2019.

There are now several companies trading on U.S. stock exchanges and dozens of private companies that focus on the drugs. Pechenik anticipates an uptick in legal work within these companies, which mostly concentrate on medical research and development since little else is legal.

Photo by Shutterstock.

Photo by Shutterstock.“As the space starts to develop in Oregon, and as other states start to have legalized psychedelic services, there will be more and more opportunities to have a specialty as a lawyer working with companies that provide psychedelic therapy,” Pechenik says.

“Potentially—and this may be more than a decade down the road—there could also be an adult use or recreational psychedelics market.”

What comes next for AIMS’ patients?

As psychedelics gain momentum, Tucker continues to push the federal government to provide a pathway to psilocybin-assisted therapy for patients with advanced cancer.

On Feb. 2, two days after the 9th Circuit’s decision in the AIMS Institute’s case, Tucker and her co-counsel filed a petition asking the DEA to reschedule psilocybin to Schedule II.

They have also asked the DEA to authorize their clients’ access to psilocybin for therapeutic use under federal and state Right to Try laws. The DEA said on June 28 that it would not reconsider their request, and the next day, Tucker asked the agency to confirm that its response is a final agency action.

Tucker says they plan to return to court and seek expedited review of their case.

Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., the chair of the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, played an influential role in the passage of the federal Right to Try law. In a statement provided to the ABA Journal, she said she has asked the DEA about the issues raised by patients from her state.

“I understand how personal this issue is and how hard it can be to talk about, and I appreciate the patients speaking up about the unimaginably challenging experience they are going through, sharing their stories and advocating for support to help them deal with end-of-life anxiety and depression,” Murray said.

In the meantime, Aggarwal is exploring the relationship between psychedelics and religious use. In the early 1980s, the federal government issued an exemption for peyote, a Schedule I hallucinogen, when used in the Native American Church’s religious ceremonies.

In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with a religious organization that used hoasca, a sacramental tea made from a plant containing the Schedule I drug dimethyltryptamine, in the decision Gonzales v. O Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal.

“I’m kind of leaning on religious freedom and the rights that are inherent in that framework,” Aggarwal says. “There are churches that are here in the country that my patients could potentially access, so I’m trying to align with those churches and see if I can refer my patients to them.”

Erinn Baldeschwiler started a different type of immunotherapy in June. (Photo by Yosef Kalinko/ABA Journal)

Erinn Baldeschwiler started a different type of immunotherapy in June. (Photo by Yosef Kalinko/ABA Journal)

Baldeschwiler learned in October that her cancer had stopped responding to treatment, and she received a six-month prognosis. She started a different type of immunotherapy in June. When asked about her wishes for the future, she says she wants the DEA to see the humanity in patients with terminal illnesses.

“I would love to see the stigmas overcome and for people to realize that the whole purpose of Right to Try laws is to provide relief from extreme pain and suffering,” Baldeschwiler says. “If you’re anybody who would want to deny or restrict that, I just don’t know how you can live with yourself.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.