The President's Court

Seated: Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy, Chief Justice John Roberts, Justices Clarence Thomas and Stephen Breyer. Standing: Justices Elena Kagan, Samuel Alito, Sonia Solomayor and Neil Gorsuch. AP Images

Religion and Gay Rights

Lakewood, Colorado, baker Jack Phillips describes himself as a cake artist who specializes in custom wedding cakes. But he is also a Christian who refused to create a cake for a same-sex couple’s wedding because he says it was contrary to his understanding of biblical teaching. (He also refuses to create cakes celebrating Halloween, atheism, racism or indecency.)

The Colorado Civil Rights Commission found that Phillips violated the state’s anti-discrimination law and ordered him to make custom wedding cakes for same-sex couples on the same basis as for straight couples. The Colorado Court of Appeals rejected Phillips’ First Amendment arguments that compelling him to create cakes for same-sex couples was a form of compelled speech that violated his rights of free speech and free exercise of religion.

The U.S. Supreme Court held on to Phillips’ appeal in Masterpiece Cakeshop Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission for a long time last spring and granted review only after Gorsuch had settled in as a justice. That has fueled speculation that the court’s conservatives are behind the grant.

“The underlying issue is enormously important,” says Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California at Berkeley and a contributor to the ABA Journal. “To what extent can people discriminate on the basis of their religious beliefs?”

Jack Phillips refuses to create cakes that celebrate same-sex weddings, Halloween, atheism or racism. Photo by AP Photo/Brennan Linsley, File.

Partisan Gerrymandering

The court confronts a seemingly never-ending supply of cases about racial gerrymandering. But in Gill v. Whitford, set for argument Oct. 3, the justices will consider whether there is a workable standard for outlawing excessively political gerrymandering—the drawing of legislative lines to the benefit of the majority party and to put the minority party at a disadvantage.

In this case, a federal district court struck down a plan for Wisconsin state legislative districts that has given Republicans a stranglehold on the state Assembly even though the state is evenly divided between the GOP and Democrats.

The Supreme Court last struggled with political gerrymandering in 2004 in Vieth v. Jubelirer, over redistricting in Pennsylvania. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy provided the fifth vote in a 5-4 judgment upholding the state’s plan but refused to go as far as a plurality that would have held courts should never review claims of political gerrymandering. He wrote a concurrence suggesting there might be times when such partisan line-drawing would violate the Constitution.

“The Supreme Court has struggled with this issue, to put it mildly,” says William S. Consovoy of Arlington, Virginia, the co-director of the Supreme Court Clinic at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University. “At one point, there was probably a bare majority to say that political gerrymandering is unconstitutional. A lot of those justices who joined those majorities have retired, so it’s only a prediction as to what others will hold on that.”

CellPhone Data

Twice in recent years, the court has issued rulings applying the Fourth Amendment in the context of digital communications. In 2012 in U.S. v. Jones, the court held that police attaching a GPS device to a suspect’s car and monitoring the vehicle’s movements constitutes a search. And in 2014, the court said in Riley v. California that police needed a warrant to search the contents of a cellphone seized incident to a lawful arrest.

In Carpenter v. U.S., the justices are being asked whether the Fourth Amendment permits a warrantless seizure of cellphone records that reveal the location of a suspect over an extended period of time.

“This case presents an important next step in the ongoing effort to reconcile enduring Fourth Amendment principles with the reality of a new digital world,” says the appeal, filed on behalf of a man for whom authorities used cell-tower data obtained from service providers without a warrant. The data tied the suspect to a series of armed robberies.

The information was obtained by court order under the federal Stored Communications Act, but privacy advocates say authorities sought large amounts of data without a finding of probable cause as to the suspect.

A federal appeals court ruled that the suspect had no reasonable expectation of privacy in cell location records maintained by service providers, saying they were akin to the dialed phone numbers conveyed to the phone company, which the Supreme Court held in a 1979 decision were not protected by the Fourth Amendment.

Chemerinsky says the case could be of wide importance in the digital age. “Our cellphones are constantly giving information about where we’re located,” he says. “Do police need to get a warrant to do that, or can they just go and get that information?”

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie. Shutterstock

Sports Wagering

In a high-stakes case (as it were), the justices will consider whether a 2014 New Jersey law that repealed a prohibition on sports wagering at casinos and racetracks is pre-empted by a federal statute, the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act.

In Christie v. National Collegiate Athletic Association, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and other state officials and authorities (as well as the state’s racetrack interests), are pitted against the NCAA, the major professional sports leagues and the federal government.

The state repealed its longtime prohibition on sports gambling in 2014 and gave up efforts to regulate it, which were the basis for an earlier chapter of this long-running litigation. The leagues have long sought to keep state-sanctioned sports wagering in check, and they say the state is licensing and authorizing such gambling in violation of the federal statute.

The full 3rd Circuit, based in Philadelphia, agreed. And it rejected the state interests’ arguments that the federal statute infringed on the state’s 10th Amendment rights because it neither compels a state to regulate according to federal standards nor requires state officials to administer federal law.

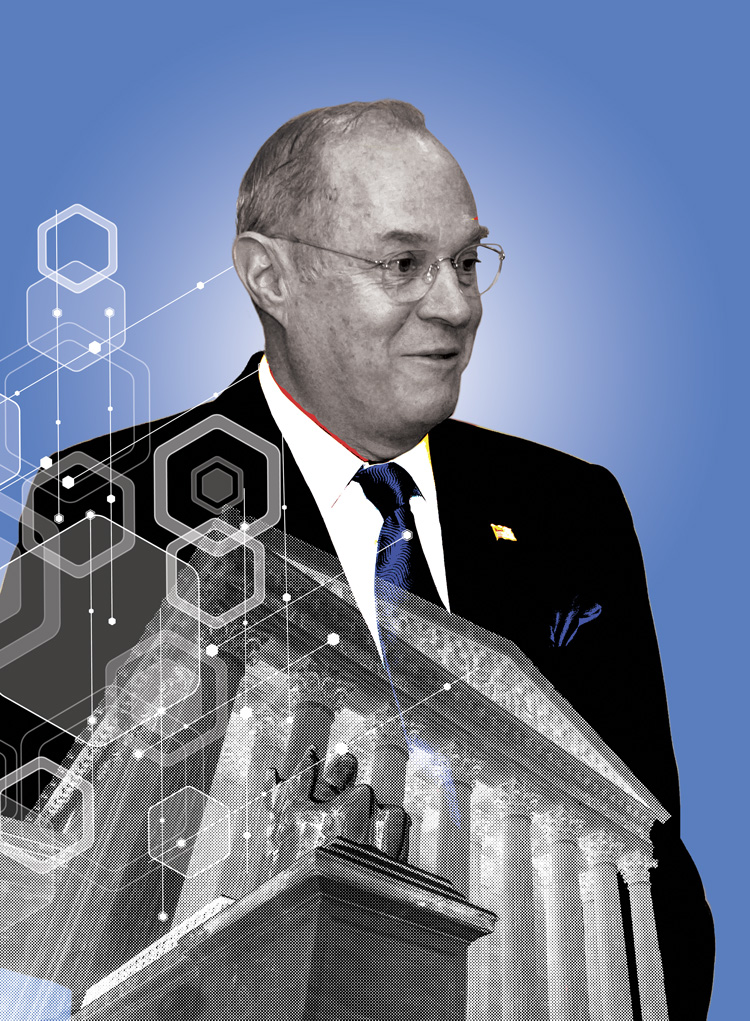

Last term, Justice Kennedy was in the majority most of the time. Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp.

The Kennedy Court

As the justices take the bench this month, it will be the first full term for Gorsuch, who asserted himself quickly during his partial tenure. Meanwhile, Kennedy didn’t fulfill retirement rumors (nor the hopes of the Trump administration) this past summer, but he has reportedly told applicants to be law clerks beyond this term that he is indeed considering retirement.

Noting that Kennedy was in the majority 97 percent of the time last term (ahead of Roberts and Justice Elena Kagan, who were tied at 93 percent), Chemerinsky of UC-Berkeley says: “It’s still the Anthony Kennedy court.”

For one more term, at least.

Mark Walsh is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C. This article appeared in the October 2017 issue of the

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.