Feb. 23, 1923: Justices hear a challenge to 'English-only' laws

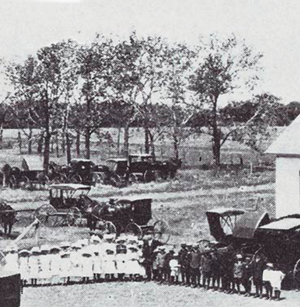

Zion Parochial School near Hampton, Nebraska, was the scene of the crime. Photographs courtesy of Nebraska State Historical Society.

On a May afternoon in 1920, a county prosecutor showed up at a one-room parochial school in rural Nebraska to watch a 10-year-old boy take part in a crime. He watched as young Raymond Parpart read aloud an Old Testament Bible story about Jacob’s ladder. The crime evolved from the fact that the boy was reading in German. Parpart’s teacher, Robert Meyer, was later charged with violating Nebraska’s Siman Act, for which he could face jail time and a fine.

During decades of upheaval in Europe, heartland America had absorbed unprecedented levels of European immigration. Even the armistice ending the Great War brought no end to lingering fears that this tide of immigrants would bring European chaos to Middle America.

In response, Nebraska legislators passed the Siman Act in 1919, forbidding foreign language instruction through eighth grade in all schools. Like the post-war “English-only” laws in many other states, the act appeared to have solid federal support. An omnibus education initiative, the Smith-Towner Bill of 1918, included a requirement for the “Americanization of immigrants” through mandatory English instruction. State legislatures were offended by federal interference in education but convinced by virulent xenophobic organizations like the American Protective League that the unfamiliar spoken word—particularly German—was disloyal and dangerous to American cultural norms. One legislator noted: “If these people are Americans, let them speak our language. If they don’t know it, let them learn it. If they don’t like it, let them move.”

Robert Meyer

The brunt of this vitriol was aimed at a growing population of Catholics and Lutherans, many Italian or German by birth or by culture. It was no coincidence that Meyer taught at a school operated by the Zion Evangelical Congregation, one of the nation’s most influential Lutheran ministries. Moreover, the Bible reading was a carefully staged act of civil disobedience designed to place before the courts a challenge to the Siman Act and other such laws.

Meyer was tried and convicted, but he refused to pay the $25 fine. On appeal, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled that enforcement of the Siman Act, like any mandatory education, was a legitimate exercise of state police power—this one directed at a potential public threat. But his lawyer Arthur Mullen—a naturalized citizen born in Canada and a former Nebraska attorney general—took a different approach before the U.S. Supreme Court. Instead of grounding his argument in a First Amendment right of religious expression, Mullen attacked the law as a violation of Meyer’s right to pursue his teaching profession, an abridgment of due process under the 14th Amendment.

By the time the nation’s highest court was to consider Meyer’s criminal case, Nebraska legislators had adopted a newer, harsher version of the act. And in February 1923, the court heard arguments that included the Siman Act, the newer Nebraska legislation and English-only cases from Iowa and Ohio.

But it was Meyer v. Nebraska that dealt the blow. In a blistering 7-2 decision delivered in June, Justice James C. McReynolds derided the laws as an affront to not only the rights of teachers but also parents who desired to have their children educated as they see fit. McReynolds also directed specific attention to the disproportionate, irrational treatment of German immigrants.

“Mere knowledge of the German language cannot reasonably be regarded as harmful. Heretofore it has been commonly looked upon as helpful and desirable,” McReynolds wrote. “The protection of the Constitution extends to all—to those who speak other languages as well as to those born with English on the tongue. Perhaps it would be highly advantageous if all had ready understanding of our ordinary speech, but this cannot be coerced by methods which conflict with the Constitution—a desirable end cannot be promoted by prohibited means.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.