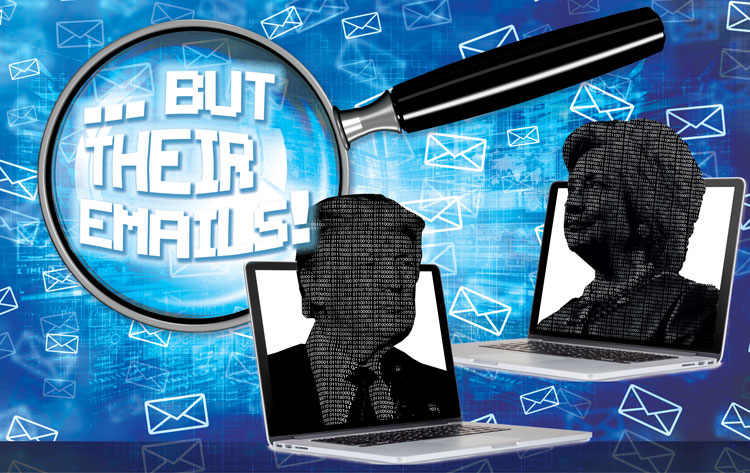

But their emails! Some of the most contentious political issues are e-discovery disputes

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp/Shutterstock

Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign stump speeches were predictable in that they were completely unpredictable. The freewheeling real estate tycoon-turned-reality-television-star loved speaking off the cuff. When he took the stage on July 27, 2016, in Doral, Florida, he was no different. Trump fired off his thoughts about a variety of topics, including what to do about ISIS, whether the U.S. should honor its commitment to NATO, his refusal to release his tax returns, his relationship with Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin, and many other things.

Most of his time on stage, however, was dedicated to addressing his main opponent in the upcoming general election, Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. The former first lady and U.S. senator from New York had become embroiled in scandal ever since it was revealed that as secretary of state, she used a private email server rather than relying on an official State Department email address. Clinton’s conduct raised ethical and legal questions—primarily relating to compliance with the Freedom of Information Act and preservation of records pursuant to the National Archives and Records Administration’s regulations, to say nothing of potential civil or criminal liability for possibly mishandling classified information. Clinton had deleted just over 30,000 emails that she claimed to be of a personal nature—an act Trump and others seized upon as the presidential race intensified.

“Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing. I think you will probably be rewarded mightily by our press,” Trump said from the Doral dais. He was apparently referencing allegations that Russian hackers had attacked the Democratic National Committee’s servers and breached Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta’s private email account and leaked a treasure trove of emails to WikiLeaks. In fact, this summer the Justice Depart- ment announced indictments against 12 Russian na- tionals as part of special counsel Robert Mueller’s probe into Russian interference in the 2016 election.

In this one apparently off-the-cuff statement, Trump illustrated the ways politics have hijacked otherwise opaque and technical e-discovery disputes. That Clinton’s legal team deleted thousands of emails during the course of an investigation is normally an obscure matter for courts to hash out. In some cases, parties have been sanctioned or suffered an adverse inference when electronic evidence goes missing.

But because the subject of this investigation was running for president of the United States, a dispute over email retention policies is now of geopolitical importance.

Indeed, a larger debate over preserving electronic evidence continues to hang over national politics. Donald Trump Jr.’s meetings with Russians, Michael Cohen’s plea bargain, Brett Kavanaugh’s contentious confirmation to the U.S. Supreme Court, Paul Manafort’s fraud convictions and an attempt at impeaching Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein all involve, at their core, electronic evidence. The near-daily headlines relating to what had once been a fairly obscure set of federal laws has helped breathe new life into the field of e-discovery.

The fact that electronic evidence drives investigation and inflames the news cycle is not new. In 1986, Oliver North and John Poindexter thought they deleted thousands of emails from their computers at the National Security Council relating to what would become known as the Iran-Contra affair. Instead, the emails were recovered and became part of the criminal case against the men, both of whom were convicted but saw their verdicts reversed on appeal.

Photo by Cynthia Johnson/The Life Images Collection/Getty Images

nothing really disappears

In the years since Iran-Contra, the technology has become more sophisticated while producing exponentially more data. Conversely, the naivete displayed by North and Poindexter in relation to how technology and data work seems to remain. The fact is that nothing ever really disappears. If electronic evidence is involved, chances are the information in those communications will surface, regardless of whether it is deleted or hidden.

Unlike paper records, deleting or destroying electronic evidence is not a practical way to cover up a crime. In fact, FBI specialists managed to recover about 15,000 deleted emails from Clinton’s supposedly scrubbed server. Of those, about 5,600 were deemed work-related, though many were duplicates of emails Clinton had already turned over.

More recently, investigators seized two BlackBerrys and recovered several hundred megabytes of data in the Cohen prosecution. The government was even able to recover approximately 731 pages of encrypted information from apps like WhatsApp and Signal.

E-discovery provides irrefutable evidence in many matters. But even with this capability to uncover data from the digital scrapheap, the practice can be messy, uncertain and prone to failure. In the 2010 high-profile e-discovery matter Pension Committee of the University of Montreal Pension Plan v. Banc of America Securities, Judge Shira Scheindlin of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled that attorneys need to take reasonable steps to preserve evidence, but that courts cannot expect a standard of perfection.

“The standard remains,” says Scheindlin, now retired from the bench. “For Clinton’s team, the question is whether she made an effort to preserve those emails once it became obvious it could be relevant for litigation or a congressional inquiry.”

Email and electronic records must not be destroyed if litigation is imminent. A technician with Platte River Networks deleted an archive of Clinton’s emails in March 2015 using a program called BleachBit. Weeks earlier, a House committee had ordered that all emails be preserved. The technician told the FBI that he had been instructed to delete the emails in December 2014 and had forgotten to do so before having what he called an “ ‘oh shit’ moment.”

The technician, Paul Combetta, however, later admitted to the FBI that he had been aware of the order and used BleachBit anyway. However, in May, then-FBI Director James Comey gave him immunity in exchange for his testimony. Two months later, Comey cleared Clinton of criminal wrongdoing, saying that while he could not “find a case that would support bringing criminal charges on these facts,” he nonetheless concluded that Clinton had been “extremely careless.”

E-discovery specialists point out that the law takes a much more nuanced view of when a failure to preserve electronic evidence is a punishable offense. In 2015, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure were amended to offer defendants an opportunity to produce evidence from alternate sources if electronic evidence is deleted or destroyed.

Specifically, under the amended Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 37(e), if electronically stored information that should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation is lost because a party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve it, and it cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery, the court can only impose sanctions if it finds the party acted in bad faith. And even if Clinton’s actions did lead to evidence disap- pearing forever, a crime was still not likely committed.

“First of all, you have to apply the proper standards, regardless of political agenda,” says Craig Ball, a Texas-based attorney who has served as a court-appointed special master in e-discovery disputes. “If you are considering the issue for a civil matter, then discovery must be proportional to the matter; if it is criminal, then a higher level of proof is required.”

Jason Krause is a freelance writer based in Madison, Wisconsin.