Political unrest, violence have forced millions to migrate and seek protection of the rule of law

Photo Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

Raquel Aldana’s interest in the cause and effect of international migration is both personal and professional.

She was born to a Guatemalan father and a Salvadoran mother and raised in El Salvador. They fled the country in 1980, at the start of the 12-year civil war between leftist revolutionaries and government forces that left more than 75,000 Salvadorans dead.

Aldana was a child, but she remembers seeing bodies on the streets when her family walked to the market. She heard later that her father was questioned about his literacy work, during a time when students and community activists were shot as a warning to others.

“My father felt unsafe in El Salvador, and because he was from Guatemala, I know that we moved fairly quickly to Guatemala, escaping El Salvador,” she says.

But Guatemala was embroiled in its own civil war—one that would last 36 years and kill more than 200,000 Guatemalans. Aldana and her family stayed only two years, leaving for the United States in 1982 in a wave of Central American migration.

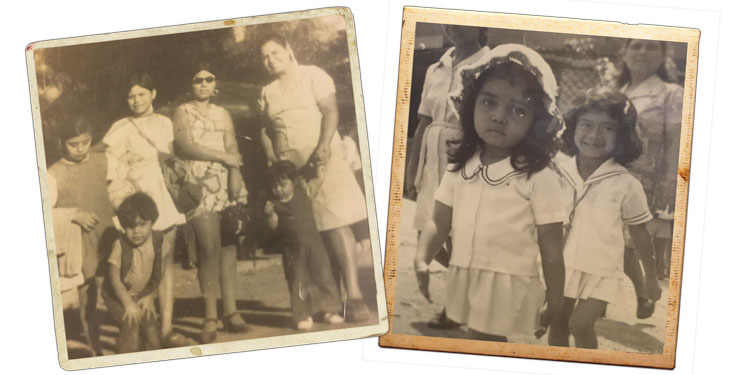

Early photos show Raquel Aldana (in foreground at right), who fled El Salvador with her family (at left) at the start of its civil war. Courtesy of Raquel Aldana.

Her mother considered crossing the U.S. border with her three children without authorization when Aldana’s brother was conscripted at age 12 for military service. Her father was a pastor, so her parents succeeded instead in securing a religious worker visa.

“In all honesty, had asylum or refugee status been available to us, we might have qualified,” says Aldana, who was 10 at the time. “We probably had enough to establish a case; but of course, then and now, the protections under law were not being given to this population.”

They went first to Florida, where her father worked in a church, but they then moved to Los Angeles to be near family. Her parents worked in clothing factories until her father got a job as a pastor in Phoenix.

Aldana graduated from Arizona State University and Harvard Law School, and worked for the Center for Justice and International Law, a nongovernmental organization in Washington, D.C., that works to improve human rights situations in the Americas.

She litigated cases involving Latin America before the Inter-American Commission and Inter-American Court of Human Rights until carrying her calling to academia, where she focused her research on transitional justice, criminal justice reforms and sustainable development in Latin America and immigrant rights in the United States.

Raquel Aldana: “The problem is not weak states; they are corrupt states, or they are failed nations.” Photo by Tony Avelar/ABA Journal

While on the faculty at the McGeorge School of Law in Sacramento, California, she founded and directed its Inter-American Program in Guatemala. The study abroad program prepares law students from the United States and Guatemala to work with the Latino population in the United States or on Latin American matters.

“It was an interesting model because it was fully bilingual, and it was really focused on understanding the issues that lead to migration,” says Aldana, who is now the associate vice chancellor for academic diversity at the University of California at Davis and a professor at its law school. “It was really taking migration and forced migration specifically to understand the much deeper story that provoked displacement from the region to the U.S.”

Driving displacement

While there isn’t a formal legal definition of “migrant,” the United Nations says most experts agree it is someone who leaves his or her home country regardless of the reason.

The number of people who were displaced as a result of persecution, conflict or violence around the world increased from 43.3 million in 2009 to 70.8 million in 2018, according to the latest Global Trends Report by the UNHCR, the U.N. Refugee Agency.

Of those, 25.9 million were recognized as refugees and 3.5 million people were seeking asylum in a country other than their own. Under the 1951 Refugee Convention, a refugee is defined as a “person who, owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

Regional treaties and declarations in Africa and Latin America expanded this definition to include generalized violence, internal conflicts and external aggression, among other circumstances.

The UNHCR reports that an additional 41.3 million people had been displaced within their own countries by the end of 2018.

Elizabeth Ferris is a research professor at Georgetown University’s Institute for the Study of International Migration who co-authored an issue paper that coincided with a 2018 ABA Rule of Law Initiative conference, both titled “When People Flee: Rule of Law and Forced Migration.” She contends that the absence of the rule of law contributes to state fragility, which often leads to forced migration.

Known drivers of displacement—persecution, conflict and violence—are often grounded in “unjust laws, weak governance structures and dysfunctional accountability mechanisms,” Ferris wrote then. Other factors, including extreme poverty, intensify the fragility of states.

In 2015, refugee families from Syria’s Kobani district lived in tents in Turkey’s Suruc district. Shutterstock

When countries lack the capacity to stop violence and corruption, and their legal and law enforcement systems lack the ability to hold perpetrators responsible, their people often have no other choice but to seek protection elsewhere.

The largest number of refugees came from Syria for the past four years, with 6.7 million fleeing the country by the end of 2018, according to the UNHCR. More than two-thirds of the world’s refugees came from Syria and just four other countries: Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar and Somalia.

“Putting in place solid laws and judicial systems and a security sector are all really key to finding solutions for people who are displaced and for preventing displacement,” Ferris says. “We are really trying to get legal experts working in this area, the rule of law, to start thinking about displacement in new ways.”

Corrupt states and failed nations

Aldana is one such expert. She was in Colombia last summer teaching a class that compared forced migration in Central America and Venezuela. Nearly 4 million people have fled the South American country since 2015 because of political unrest, violence and shortages of food and medicine.

She asked her students: How do we keep Venezuela from being Central America 30 years from now?

“If we make the same mistakes that we made in Central America post-conflict during the peace-building process, we’re going to have exactly the same problem in Venezuela,” Aldana says. “That is a sad statement, but you can’t separate state-sponsored violence from privatized violence.”

Aldana created a four-part framework to define the absence of the rule of law in Central America, starting with the absence of the state in basic social services. Guatemala has one of the lowest tax rates in Latin America and invests minimally in education, health and infrastructure.

In many rural areas, she says there are no schools, and children die of diarrhea from contaminated water.

There is also the indifference of the state, which often fails to implement laws intended to protect the most vulnerable. Many countries in Central America have modernized their criminal justice systems, but they continue to ignore crimes affecting people who are poor or marginalized.

“Those crimes, which range from domestic violence or gang violence to other types of common violence, aren’t a priority for the state,” Aldana says. “They essentially could care less that these individuals are being victimized.”

Another factor, which Aldana calls “licit corruption,” occurs when laws are effectively enforced but benefit few people. As one example, metal mining companies in Guatemala—that largely come from the United States and Canada—retain most royalties, but they do not answer for harms they bring to local communities.

Illicit corruption also contributes to the absence of the rule of law in Central America. In recent years, the presence of organized crime and drug traffickers has enhanced or replaced the influence of the military over states during their wars.

“It’s either underenforcement or manipulation of law, that’s what the absence of law looks like in the Americas,” Aldana says. “The problem is not weak states; they are corrupt states, or they are failed nations.”

Breaking free

Luis Mancheno grew up in an upper middle-class family in Ecuador. His parents made sure he and his two sisters attended good schools and went to Disney World in Orlando, Florida, but they also enforced strict rules.

Their children went to Bible study and to church on Sunday. They weren’t allowed to read Harry Potter, and they certainly weren’t allowed to show interest in members of the same sex.

Luis Mancheno feared for his life as a gay man in Ecuador and fled at 21. © Geoff Levy

Mancheno realized he was gay at 14. When his parents found out four years later, they beat him and took him to conversion therapy.

“I felt trapped because I was dependent on my parents to pay for my tuition, and at the same time, it’s uncommon for anyone to live on their own unless you are married in Ecuador,” says Mancheno, who was in law school at the time. “I had to be part of the cycle of domestic violence at home, and I tried to handle it as much as I could.”

He reached his breaking point one night when he and a friend were out at a secret gay bar. He remembers dancing and taking a drink from a stranger, and then waking up behind the steering wheel of his car. It had crashed into a light post on the edge of a cliff.

Mancheno was injured and bleeding, and his friend was unconscious in the back seat. He knew someone had tried to kill him, but when he went to the police, they laughed and told him he shouldn’t go back to that bar.

“After that, I was feeling incredibly unsafe for my life, and I decided to flee Ecuador,” he says.

He applied for an exchange student program, and a few months later, he was at Willamette University in Oregon. He met a student attorney volunteer at a human rights clinic there who worked to get asylum for people fleeing persecution.

Mancheno discovered he could make his own case due to his suffering extreme violence in Ecuador. He was granted asylum in 2009, when he was 22.

After graduating from Roger Williams University School of Law in Rhode Island, he represented men and transgender women in removal proceedings with the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project in Arizona. Later, as part of the inaugural class of Immigration Justice Corps fellows in New York, he represented detainees in immigration and federal courts with the Bronx Defenders.

Now, as a supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society, Mancheno co-manages the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project, which provides free legal representation to low-income immigrants facing deportation.

He has represented dozens of asylum-seekers who were persecuted because of their sexual orientation and has heard many stories similar to his own, especially from those fleeing Central America.

“Impunity is incredibly high in those countries, especially when it comes to LGBT people,” he says. “They have laws against murder, assault and rape, but the issue is that enforcement of those laws, especially when the victims are vulnerable populations, is almost nonexistent.”

Meeting the challenges

Migrants face more rule of law challenges as they flee their home countries.

As controls on migration become tighter, they are often forced to rely on smugglers or traffickers to take them across borders. They pay significant amounts of money to traverse dangerous routes, which makes them more susceptible to abuse, exploitation and death.

Amnesty International uncovered human rights violations facing the thousands of migrants and refugees who trekked across Africa to Libya, hoping to make it to Europe. They have been tortured, detained, sold as slaves and killed by Libyan officials, militias and smugglers.

European Union member states, including Italy, have been criticized for restricting the flow of refugees and migrants across the Mediterranean, despite the dangers they face in Libya.

In the United States, the Trump administration said it would make many asylum-seekers entering at its southern border await decisions on their claims in Mexico. The administration also announced it would reject anyone who failed to apply for protection in at least one country on the way to the United States.

Migrants in Mexico are often targeted by gangs and organized crime while seeking protection from the violence in their own countries. Human Rights First reported that kidnappings in Ciudad Juárez, the city just south of El Paso, Texas, increased by 100% in the first six months of 2019.

Migrants also face rule of law challenges when they arrive at their intended destinations.

If they are seeking protection, they must first prove that they are a refugee. Ferris contends that the process is often lengthy and bureaucratic, and in many countries, it falls short of international standards.

“The whole system is set up with this binary distinction between refugees and migrants, yet in practice there are a lot of gray areas, like people who leave because they can’t get enough food—but they can’t get enough food because of government action or conflict,” she says.

She adds that under the 1951 Refugee Convention, those who enter a country illegally should not be punished.

“People fleeing a lot of really bad countries can’t get out of the country legally,” she says. “Think about Nazi Germany—without smugglers, many more millions of Jews would have perished.”

While one challenge is whether migrants have access to the asylum system, another is whether they have fair access.

Andrew Schoenholtz is the co-director of Georgetown Law’s Center for Applied Legal Studies, where he works with students in representing asylum-seekers. He says most Americans wouldn’t know what to do in those proceedings, let alone people from other countries who are unfamiliar with the U.S. legal system.

“Access to lawyers is absolutely critical, which is why many of us have been in favor of mandated representation for people who cannot afford their own lawyers in deportation hearings,” he says.

Migrants may also struggle to provide the documentation necessary to apply for asylum, receive humanitarian aid or register their children for school. They may also be unable to register the births of children in their new countries.

Those who want to work may be ineligible for a permit or encounter a burdensome process. For instance, many professions are closed to refugees in Jordan, while asylum-seekers in Germany must wait three months before they can work.

Countries that limit social services and employment opportunities have forced many migrants and refugees into the informal sector, where they often encounter unsafe and unfair working conditions, discrimination and exploitation.

Forging ahead

Growing up as a refugee in the United States wasn’t easy for Kuong Ly.

Born in Vietnam, he was the son of refugees from Cambodia who fled the Khmer Rouge regime after being forced into labor camps in the 1970s. Led by dictator Pol Pot, the brutal regime killed nearly 2 million people through execution or through starvation and disease.

His parents moved their five children from Vietnam to the United States in hopes of rebuilding lives free of war and persecution, arriving in Boston in 1990. They sought asylum and were sponsored and resettled in a nearby suburb by a coalition of individuals from varying religious backgrounds who assisted Southeast Asian refugees.

Ly, who was the youngest in his family, recalls that they became dependent on social welfare programs. His parents were low-wage workers and later ran a small business, and they struggled to achieve financial stability.

“There were barriers in the United States that prevented us from escaping the cycle of poverty and the challenges facing immigrant and refugee communities,” he says. “Not understanding the language and the culture were two main things we faced.”

Despite the challenges, Ly focused on his education. He went to Boston College and was awarded the Truman Scholarship, a prestigious fellowship for those pursuing public service careers. He continued on that track, receiving the Marshall Scholarship and earning master’s degrees in international human rights law from the University of Essex and in international relations from the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

A skull display at the Choeung Ek museum in Cambodia memorializes the 2 million people killed by the Khmer Rouge regime. Photo by Tang Chhin Sothy/AFP/Getty Images

He graduated from the UCLA School of Law and received a fellowship to work with a public interest law firm in Boston. He also worked with Northeast Legal Aid in Massachusetts, providing legal representation to the second- and third-largest Cambodian American communities in the country.

Ly, who is currently a law clerk for the land court department of the Massachusetts Trial Court, says that his experiences as a refugee and growing up in the margins of society strengthened his commitment to helping create a more just society.

“At the core of who I am is an unwavering belief that the law has the capacity to not only be fair, but it has the capacity to protect, rather than hurt, those most vulnerable when the law is wielded correctly,” he says.

Managing migration

Raquel Aldana encouraged her summer students in Colombia to think of solutions to rule of law challenges.

She showed them examples of agencies working directly with communities to create alternative models for addressing sustainable development, such as the United Nations Development Programme’s contributions to programs that support young entrepreneurs around the world.

Aldana has also looked at failed drug policies in the United States and how they contributed to drug trafficking from more vulnerable regions of Latin America. She contends that the United States should follow European countries in considering legalization of certain drugs.

“They will take time, but if we do those two things, it would be huge toward addressing this problem,” she says.

The U.N. General Assembly hosted the first high-level summit on large movements of refugees and migrants in September 2016. It resulted in the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, which was signed by 193 member states to reaffirm their commitment to protecting people on the move.

The declaration also paved the way for the Global Compact on Refugees and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

Kuong Ly’s parents fled the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia after being forced into labor camps in the 1970s. Photo courtesy of Kuong Ly

The U.N. General Assembly affirmed the Global Compact on Refugees in December 2018. It calls on governments, nongovernmental organizations, private sector, international financial institutions and civil society to work together to ease pressure on countries that welcome refugees, build their self-reliance and expand access to resettlement.

The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration is the first U.N. global agreement related to international migration. Also adopted in December 2018, it outlines 23 objectives for better managing migration at local, national, regional and global levels.

An expert working group that met at the 2018 ROLI conference provided rule of law approaches to help address ongoing flows of refugees and migrants. In January 2019, the ABA House of Delegates adopted a resolution that urged states and entities working to implement the two global compacts to take additional steps to address the causes of displacement and forced migration.

It also asked them to develop policies that discourage the criminal prosecution of migrants and refugees, encourage the accountable use of prosecutorial discretion and protect migrants and refugees from discrimination.

Aldana remains hopeful that the progress made so far and other innovative solutions will help countries reach a level of stability that allows their people to stay home.

“In the end, that’s really what you want,” she says. “In my mind, the dream of Central Americans should not be migration to the United States. It should be a choice that could happen because that’s a good thing, but it should not be a forced phenomenon.”

This article ran in the Winter 2019-2020 issue of the ABA Journal with the headline “Desperately Seeking Sanctuary: Political unrest, violence and food instability have forced millions to flee their countries and seek the protection of the rule of law.”

Correction

Due to an editing error, the print version of “Desperately Seeking Sanctuary,” Winter 2019-2020, did not correctly refer to one of Raquel Aldana’s four parts of her framework to define the absence of the rule of law in Central America as “licit corruption.”The Journal regrets the error.