March 9, 1916: Pancho Villa’s Battle of Columbus

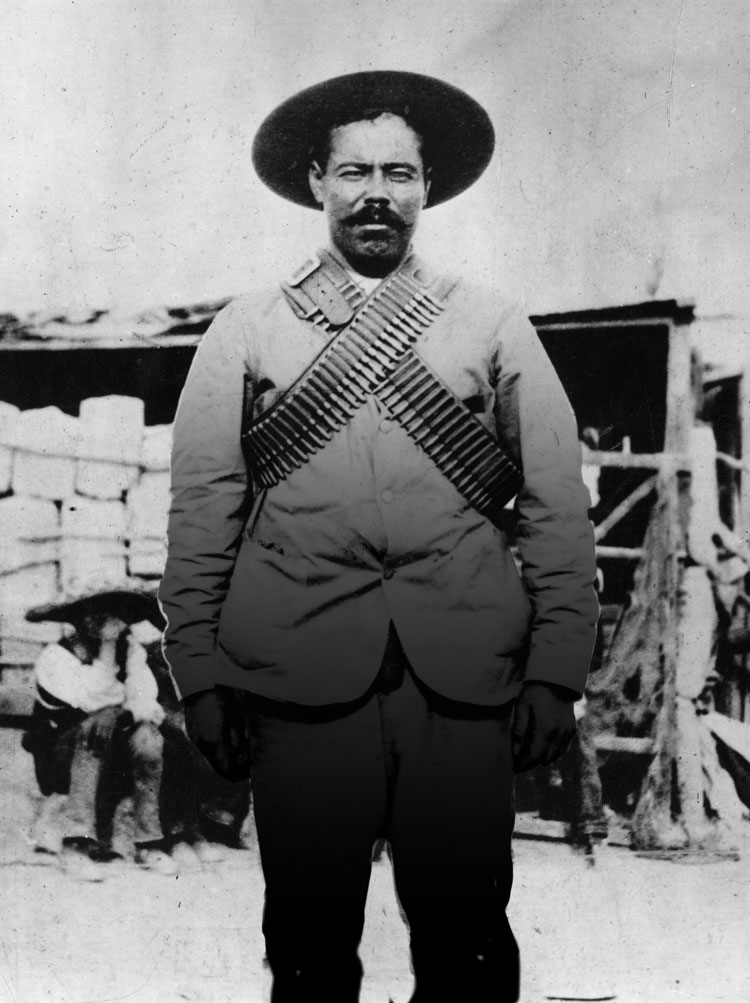

Photo of Francisco “Pancho” Villa by Topical Press Agency/Stringer/Hulton Archive/GettyImages

In the early morning hours of March 9, 1916, a small cavalry of nearly 500 rogue Mexican soldiers from across the U.S.-Mexico border stormed into the sleepy desert town of Columbus, New Mexico.

Sitting 80 miles west of El Paso, Texas, Columbus was little more than a railroad stop. Its population was only 1,300, including soldiers and their families stationed at Camp Furlong. But by the time the marauders fled the town—repelled by machine guns—at least 67 of them lay dead.

But 18 Columbus residents were also dead or dying, including 10 civilians. Four of the civilians had been dragged from the Commercial Hotel and executed. A broad swath of the town lay in ruin, leveled by fires and explosions. And Americans along the border were dumbfounded that revolutionary violence in Mexico had suddenly lurched north.

The soldiers were led by Francisco “Pancho” Villa, the ruthless paramilitary leader who had dominated Northern Mexico from the start of the Mexican Revolution. Born to Durango sharecroppers in 1878 as Doroteo Arango, Villa fled Durango after shooting a prominent rancher. Adopting the name Francisco Villa, he roamed the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains, developing a widespread reputation as a resourceful and evasive bandit.

In 1910, Francisco Madero recruited him to ride against the authoritarian regime of Porfirio Díaz. For the 32-year-old Villa, it was an easy sell. In Northern Mexico, Americans and other foreigners—abetted by Mexico’s richest families—owned most of the mines, oil fields and railroads, as well as 100 million acres of ranch and agricultural lands. The overwhelming population of Mexican peasants lived the feudal existence of sharecroppers and laborers.

For the next decade, Villa fought for, and often against, successive revolutionary regimes. He was even once slated for execution before he escaped to the U.S. But when Madero was murdered in a 1913 coup d’état, Villa returned to Mexico with great fanfare in support of Venustiano Carranza. His brilliant campaigns at Tierra Blanca, Chihuahua and Ojinaga were chronicled by American journalists and a Hollywood studio. His second siege of Ciudad Juárez was watched from rooftops in El Paso, where merchants routinely traded with the Villistas.

But by the time of the Columbus raid, Villa’s alliance with Carranza had soured along with his fortunes. With Carranza’s army trained against him, Villa’s attacks on Celaya resulted in devastating losses. Broken and defeated, Villa repaired to Chihuahua and the indiscriminate violence of his past.

In a train robbery two months before Columbus, Villistas murdered 18 mining engineers—all but one an American. And just days before the Battle of Columbus, in ranch raids around nearby Palomas, at least four American ranch hands had been killed.

Outraged by the Columbus raid, Woodrow Wilson ordered a “punitive expedition” of 5,000 U.S. soldiers to follow Villa into Mexico and kill or capture him. Although the foray was abandoned as a failure in February 1917, the offense to Mexico lingered for decades—coloring negotiations over American claims against Mexico for damages during the revolution.

Congressional hearings led by New Mexico Sen. Albert Fall deemed Mexico responsible for as many as 550 American deaths on both sides of the border during the revolution, more than a few at the hands of Mexican soldiers. Mexico disregarded many of the claims, particularly regarding Villa, arguing that the former bandit had no commission as a Mexican general. However, in 1920, Villa was granted both amnesty and a generous pension that allowed him to live on a hacienda in Chihuahua. He remained there until July 1923, when he was murdered in a roadside attack.

In September 1923, a formal commission began to negotiate claims against Mexico, including those of Columbus residents.

But it was not until 1938, 22 years after the Columbus raid, that Mexico finally agreed to pay off U.S. claims—at an agreed rate of less than 3 cents on the dollar.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.