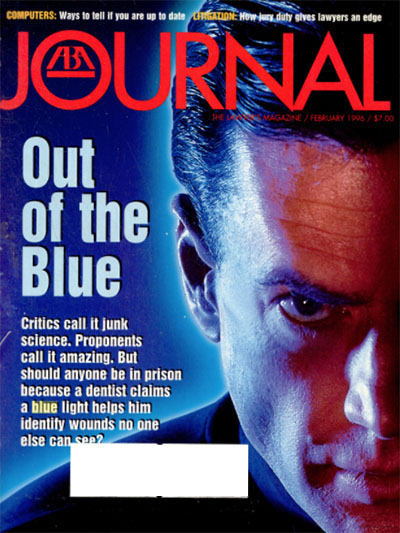

Out of the Blue

Even after the Supreme Court tried to rein in expert witnesses willing to testify at the drop of a theory, embattled dentist Michael West and his shining light prove that ‘science’ can be stranger than fiction.

If Michael H. West had stuck to what he presumably does best, he might not today be regarded by much of the scientific community as the dental equivalent of now discredited footprint expert Louise Robbins.

Robbins, who died in 1987, was a college anthropology professor whose chief claim to fame was her apparent ability to match a footprint on any surface to the person who made it.

The trouble with Robbins, who appeared as an expert witness in more than 20 criminal cases in 11 states and Canada during a 10-year period, is that her claims have since been thoroughly debunked.

And the trouble with West, a 43-year-old forensic dentist from Hattiesburg, Miss., who has made a name for himself in legal circles since the mid-1980s for his seeming ability to match bite marks with the teeth that made them, is that he reminds so many people of Robbins.

Robbins’ claims were hotly contested from the moment she first stepped foot in a courtroom. Yet she continued to testify with virtual impunity until failing health forced her off the witness stand.

West’s self-proclaimed forensic abilities also have long been questioned by many of his peers. Indeed, he resigned from one professional association in 1994 after it had taken steps to have him expelled. He was suspended for a year from another professional association, to which he was automatically reinstated this past May.

Like Robbins, though, such criticism appears to have had little or no effect on West’s legal career, which he says is going strong.

“I’m as active now as I’ve ever been,” he says.

It took years to undo the damage done by Robbins, whose testimony helped put more than a dozen people behind bars, including an Ohio man who spent six years on death row before his conviction was overturned on appeal in 1990.

The consequences of West’s testimony are just now starting to be sorted out. And compared to his track record, Robbins was small potatoes.

By his own estimate, West has appeared as an expert about 55 times in nine states over the past dozen or so years, at least a third to a half of which were capital murder cases. He says he lost his first bite mark case, in 1983, but that he has not lost one at trial since (excluding any convictions reversed on appeal).

But West’s proclaimed expertise is not limited to bite marks. In fact, he has created a comfy niche, mostly as a prosecution expert, matching not only bite marks with teeth, but also wounds with weapons, shoes with footprints and fingernails with scratches, even spills with stains.

West’s testimony has helped put dozens of defendants in prison, some for life, and at least two on death row, where they remain today.

West is perhaps best known for his controversial use of a special blue light to study wound patterns on a body. With a pair of yellow-lensed goggles and a long-wave ultraviolet light, West claims he can see things that are otherwise invisible to the unaided eye.

Criminologists have long used such a blue light to look for trace evidence at the scene of a crime. A few other forensic dentists have experimented with the use of such a light for research purposes. But West is the only one presenting himself as an expert on the subject in court.

The problem with the blue light, according to his scientific counterparts, is that West sees things under it that he cannot document and that nobody else can see. While they say there is legitimate scientific basis for suggesting that such a light can enhance features on the surface of skin that otherwise would be difficult to see, there is no evidence that such a light can make a mark that is invisible under natural light suddenly appear. Normal skin fluoresces under a blue light; damaged skin does not, they point out.

But the blue light is just part of the problem his peers have with West. Even when he was not using such a light, they say, West has claimed to see things that he has not been able to document, failed to follow generally accepted scientific techniques, and testified about his findings with an unheard of degree of scientific certainty —“indeed and without a doubt” is his standard operating opinion.

The controversy over West’s self-proclaimed expertise illustrates, at a state level, the types of issues that courts confront in deciding who qualifies as an expert witness and what constitutes scientific evidence.

The U.S. Supreme Court set the standard in 1993 for federal trials when it held that such evidence must be validated scientifically. Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 113 S. Ct. 2786. It was no longer sufficient for evidence to be based merely on generally accepted scientific principles, which had been the federal standard for 70 years and is still the rule in some states. Daubert was supposed to help keep unproven science out of the courtroom.

Despite all the questions that have been raised about his work, though, West remains in demand as an expert. This past March he testified in separate cases against two Mississippi capital murder defendants who subsequently were convicted and sentenced to death: one for the murder of a 3-year-old girl; the other for the murder of three people. West currently has other cases pending.

West is not alone either, according to his peers, who say there are more than a few others out there like him: self-proclaimed experts whose so-called expertise is dubious at best, but who regard themselves as being equal to any task.

“He is clearly a sore on the body of forensic science,” says James Starrs, a professor of law and forensic science at George Washington University and publisher of Scientific Sleuthing Review, an industry newsletter. “He is forever going beyond what other scientists are willing or able to say.”

Robert Kirschner, former deputy chief medical examiner for Cook County, Ill., which includes Chicago, says what West purports to do is closer to voodoo or alchemy than science.

“History is full of people who claimed they could see things, from ghosts to UFOs,” Kirschner says. “But claiming it and proving it are two different things.”

Kirschner, who has squared off against West in court on two occasions, says the forensic dentist’s work violates every known rule of scientific inquiry and investigation. Nor has West ever been able to document anything he claims to have done, Kirschner adds.

“The results shouldn’t be admitted in any court,” he says.

But they have been, with troubling regularity, according to Kirschner and other experts, who say some prosecutors are too willing to turn to somebody like West when they lack the evidence they believe they need to tie a suspect to a crime.

Armstrong Walters, a Columbus, Miss., lawyer who has twice crossed paths with West in court, says no district attorney in the Deep South stands a chance of re-election if a murder occurs in his or her jurisdiction and somebody does not wind up in prison for it. “West confirms whatever suspicions the police have,” he adds.

West, however, remains defiant, saying he is not doing anything that is not being done by his peers—who, he notes, just happen to be his competitors.

“These personal attacks on me are motivated by professional jealousy.”

In defending his own objectivity, West says he does not see himself as either a prosecution or a defense expert, but as an “expert for the truth.” All told, he says, he has eliminated many more people as suspects than he has implicated.

West is dedicated, if nothing else. He once had himself bitten on the arm, had the bite mark biopsied and then photographed the wound under different lights over a period of several months, all in the name of science.

He also justifies his choice of terminology, describing the “indeed and without a doubt” opinions he favors as being synonymous with the dictionary definition of certainty and less confusing to a jury than the “reasonable degree of medical/dental certainty” language preferred by his peers.

And West, who still enjoys the support of some prosecutors, shows no signs of backing down. In a rambling, three-hour telephone interview, he at times sounded bowed, but unbroken. Time and science, he insists, will someday prove him right. “I keep losing in committee and in the media,” he says. “But I keep winning in court, where it counts.”

Asked about the consequences of constantly having to defend himself, he says it has left him “embarrassed, ashamed, financially strapped, humiliated, paranoid and extremely anxious,” but otherwise has had “no effect whatsoever.”

But he is not taking it lying down. West is suing the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, from which he resigned in 1994, after its ethics committee recommended that he be expelled for allegedly failing to meet professional standards of research, misrepresenting data to support a general acceptance of his techniques, and offering opinions that exceed a reasonable degree of scientific certainty.

His suit, filed last year in U.S. District Court at Hattiesburg, Miss., contends, among other things, that the academy’s attempt to expel him violated his due process rights and caused him emotional distress. (As of mid-December, a motion by the academy for summary judgment was pending.)

West also was suspended two years ago from the American Board of Forensic Odontology. The board found that West had misrepresented evidence and testified outside his field of expertise. But he has not sued that organization, of which he is once again a member in good standing.

For a dentist, though, West seems to know a lot about feet. In 1990, for instance, he identified a footprint on a murdered girl’s face in Jefferson Parish, La., outside of New Orleans, as having been made by an athletic shoe found in the apartment of a neighbor.

That neighbor, Thomas Abadie, facing a possible death sentence, eventually entered a plea to manslaughter and was sentenced to 31 years in prison.

A year later, in the same parish, West matched a bruise on a murdered boy’s stomach to a hiking boot belonging to the boy’s mother, Patricia Van Winkle.

Although Van Winkle was convicted of manslaughter and received a 21-year sentence, her conviction was overturned on other grounds this past June by the Louisiana Supreme Court. State v. Van Winkle, 658 So.2d 198.

Robert Toale, the lawyer who represented both Abadie and Van Winkle, says there is no end to West’s arrogance. Toale says he once asked West on cross-examination about his margin of error. He says he will never forget the response.

“Something less than my savior, Jesus Christ,” he quoted West as saying.

But West’s apparent expertise goes beyond teeth or feet. In 1990, in the Gulf Coast city of Pascagoula, Miss., he matched the fingernails of a murder victim, which he had removed and mounted on sticks, to scratches on the forearms of the defendant, Mark Oppie. Oppie, who also was looking at a possible death sentence, agreed to a manslaughter plea that left him eligible for parole in about six years.

And, in what still may be the most unusual manifestation of his supposed forensic abilities, West showed up in Xenia, Ohio, near Dayton, in 1993, where, presented as a burn pattern specialist by prosecutors, he testified at the trial of a 17-year-old youth charged with involuntary manslaughter in the death of his disabled 6-year-old sister, who had been chemically burned by bleach.

The defendant, who maintained that his sister had spilled bleach on herself, was acquitted, despite testimony by West that the bleach had been poured deliberately on the girl.

“How he got qualified as an expert on bleach spills is between him and the judge,” says defense lawyer, John Rion, who sarcastically calls West “the world’s expert on everything. I thought [his testimony] was preposterous.”

But West says none of it is as preposterous as it may seem.

Teeth and feet are no different from fingernails, pliers, tire irons, bleach or, for that matter, anything else that can be used as a weapon, he says. And just like guns and knives, each has certain class and individual characteristics that can be identified and compared to the wound pattern it is believed to have made to determine whether they match, he adds.

Questions about West’s forensic abilities first were raised in connection with an investigation into the 1990 stabbing deaths of three elderly people near Meridian, Miss., in the central part of the state. Nearly two weeks after the killings, West was called in to examine a butcher knife believed to have been used in the crime, as well as the hands of the chief suspect, Larry Maxwell.

West not only identified the knife as the murder weapon, but in his first application of the blue light claimed he could see an impression made by the exposed rivets in the handle of the knife on Maxwell’s palm. West says he took photos of this phenomenon, which he then took the liberty of naming after himself, but accidentally overexposed the film, which reduced him to drawing on photocopies of the defendant’s palm what he says he saw.

Maxwell, who spent more than two years in jail awaiting trial, was freed in 1992 after a judge ruled that West’s blue light testimony was inadmissible.

“It may well be that Dr. West is a pioneer in the field of alternative light imaging for the purpose of detecting trace wound patterns on the human skin, and it may well be that the future will prove that his techniques are sound evidentiary tools that result in the presentation of inherently reliable expert opinions. But at this time I am not so convinced,” Kemper County, Miss., Circuit Judge Larry Roberts wrote.

Maxwell, who also alleges he was beaten by police, is suing West, along with several local law enforcement officials, in U.S. District Court at Jackson, Miss., on charges of false arrest and use of unreasonable force. Maxwell, whose suit is set for trial in April, is seeking damages of $10 million.

“Essentially, [West’s testimony] was the only evidence they had,” says Jackson lawyer Karla Pierce, who represents Maxwell in the civil suit.

West, for his part, stands by his testimony. “It was a perfect match,” he says of the knife and the pattern he says he observed on Maxwell’s hand.

If the Maxwell case didn’t damage West’s credibility, word of what happened to Johnny Bourn might have destroyed it for good. In 1992, West positively identified a bite mark on an elderly rape and robbery victim in Jackson County, Miss., which includes Pascagoula, as having been made by Bourn.

Unfortunately for West, hair and fingerprint evidence from the crime scene did not match the defendant’s. And a DNA analysis of the assailant’s skin, obtained from fingernail scrapings of the victim, positively excluded Bourn.

The charges were dropped, but by then Bourn had spent about 1&farc12; years in jail awaiting trial.

“I know [Bourn] bit that woman,” West says today, first suggesting that the DNA results were faulty and then speculating on the possibility of multiple assailants. “The question [presented by the DNA] is whether he raped her. He may have had an accomplice.”

That kind of controversy has dogged West throughout his career. In 1990, for example, his testimony helped seal the fate of Henry Lee Harrison, a Jackson County man convicted and sentenced to death for the 1989 rape and murder of a 7-year-old girl.

West testified that he had identified more than 41 bite marks covering the victim’s body, all of which he said had been inflicted by Harrison, some while the girl was alive, some after she was dead.

“He had very unique teeth,” West says of the defendant. “And they all showed up in the wound pattern on the victim’s body.”

However, two other experts who since have examined the evidence scoff at West’s findings. One says the marks on the girl’s body cannot be identified. The other says they probably were ant bites.

“To say these are human bite marks is ludicrous,” says Richard Souviron, a forensic dentist from Miami who is widely regarded as one of the nation’s foremost bite mark experts. Souviron is perhaps best known as the expert who matched serial killer Ted Bundy’s teeth to bite marks on one of his victims. He also was chair of the ethics committee of the forensic dentists board, which recommended that West be suspended.

“Anytime you take a body and dump it in a swamp, you’re going to have insect activity. Anybody could you tell you that,” he says.

West replies that “I’m not saying there weren’t ants on the girl. But they’re not going to bite a pattern into the victim’s body that exactly matches the defendant’s teeth.”

Harrison’s conviction and sentence were overturned in 1994 by the Mississippi Supreme Court, but not because of West. The court ordered Harrison retried because it found that the state failed to disclose evidence supporting the rape charge and the judge refused to authorize funds to allow the defense to hire an expert to rebut it. Harrison v. State, 635 So.2d 894.

Two years ago, West’s testimony also was instrumental in helping convict Anthony Keko for the 1991 murder of his estranged wife, Louise, in Plaquemines Parish, La., near New Orleans.

West, who had Louise Keko’s body exhumed more than a year after her death, identified what he said was a bite mark on her shoulder as having been made by her estranged husband. West had the bite mark removed for safekeeping, but later said it had been erased after it was accidentally placed in embalming fluid.

Defense experts, on the other hand, said they could not be sure the mark was even a bite, let alone identify the person who might have made it.

Souviron, one of the defense’s experts, says the mark appears to be a post-mortem artifact, or an unexplained injury that occurred at some point after the victim’s death. “It could have been anything, really.”

Yet the jury chose to believe West, whose testimony provided the only direct evidence linking Keko to the crime, according to his lawyer, Eddie Castaing. After four hours of deliberation, Keko was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

In December 1994, however, the trial judge, voicing doubts about West’s forensic abilities in light of the previously undisclosed disciplinary proceedings against him, reversed Keko’s conviction and ordered a new trial.

Keko is free on bond while he awaits a new trial, which was tentatively set to begin early this year. But his lawyer is trying to prevent West from testifying again, because without him prosecutors concede they do not have much of a case.

“It’s either him or nothing,” says Plaquemines Parish assistant district attorney Charles Ballay, the prosecutor.

Ballay says he thinks too much importance has been placed on West’s role in the case. West only spent about a day on the witness stand in a trial that lasted 23 days, he says. And the circumstantial evidence against Keko, in and of itself, was very persuasive, he adds.

“It wasn’t like the jury was being asked to believe West and only West,” he says. “There was a lot of other evidence that pointed to Keko being the murderer.”

That evidence alone, though, probably is not strong enough to convict, Ballay concedes. West’s testimony is the only evidence, he says, placing Keko at the crime scene, which may explain why he and other prosecutors still vouch for West.

Ballay says there is nothing new or mysterious about West’s techniques. The only thing that is new, he says, is that these techniques are now being applied to the field of forensic science for the first time.

James Maxwell, the Jefferson Parish, La., assistant district attorney who prosecuted Abadie and Van Winkle, says flatly that he thinks West is ahead of his time.

“I’m quite confident in the guy,” he says. “I have a lot of faith in him. And I think he makes one heck of a witness.”

Maxwell says he could not say whether he would use West again, only that he has not had another opportunity to do so.

West, though, is still at it. This past March, while he remained under suspension from the board of forensic dentists, in separate trials only days apart, West helped Mississippi prosecutors obtain first-degree murder convictions against two men who are now on death row.

One of them is Kennedy Brewer of Brooksville, Miss., who was sentenced to die for the 1992 rape and murder of his girlfriend’s 3-year-old daughter.

West identified 19 bite marks on the girl’s body that he said had been made by Brewer, all of which he claimed to have matched to Brewer’s upper teeth. The defense, once again, called on Souviron, who said the marks appeared to have been made by insects.

But even if they were not insect bites, Souviron says, the marks could not have been made the way West had claimed. It would be impossible, Souviron says, to bite someone that many times without leaving a single bite mark from the lower teeth.

“You could not make bites the way [West] says these bites were made,” Souviron notes. “It’s crazy.”

Crazy or not, the jury believed it, a result which troubles Brewer’s defense lawyer, Thomas Kesler, more than any other case he has tried in 16 years of practice.

Kesler, of Columbus, Miss., is no bleeding heart: He has represented two other defendants in capital murder cases; as a prosecutor, he once tried a murder case in which the defendant received the death penalty. And he concedes that a reasonable person might look at the evidence against Brewer and conclude that he was guilty.

But Kesler still has his doubts. Without West’s testimony, he says, the case against Brewer was not only circumstantial but paper-thin. And the defendant, who had refused to even consider a plea bargain, has always maintained his innocence, Kesler adds. “It’s the kind of case that gives a lawyer heartburn.”

John Kenney, chief forensic odontologist for the Cook County, Ill., medical examiner’s office, and the current president of the board of forensic odontology, says that even though West is back in the good graces of the organization, he is not home-free. From now on, every time West goes into court, Kenney says, he will have to acknowledge having once been suspended by his peers.

“As forensic scientists, the only thing we have is our reputation,” he says. “This blemish on his record is something he’ll have to contend with for the rest of his professional life.”

But John Holdridge, a New Orleans lawyer whose complaints about West prompted the two professional groups to take disciplinary action against him, says the fact that West is still testifying at all shows that some courts, nearly three years after Daubert, remain unwilling or unable to distinguish science from science fiction.

“I think it shows that judges aren’t willing to exercise the discretion that’s been given them in any meaningful way,” Holdridge says. “They just leave it up to the jury, which is obviously in no position to make these kinds of decisions.”

The forensic science community has done its job with respect to West, he says. Now it is up to the courts to do theirs.

Sidebar

Real science

To admit scientific evidence, a judge following Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmacetuicals, 113 S.Ct. 2786 (1993), must determine that:

Proposed testimony is based on “good grounds” of what is known in a particular field.

The theory or technique can and has been tested.

Testing involved peer review and publication.

Error rates and control techniques will affect admissibility.

While a judge must consider these factors, there is no checklist for determining admissibility in every instance. Publication of a theory does not imply reliability, and some novel theories may not have been published.