Devastated by office chemicals, an attorney helps others fight toxic torts

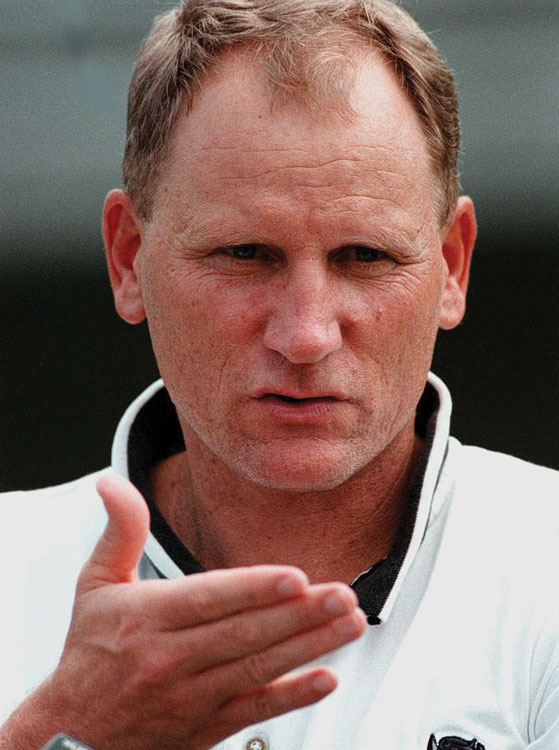

Photo of Dan Allen before the onset of ALS courtesy of Alan Bell.

I called Laura after Dr. Ratner had seen Dan. “Look, this is serious,” I said, after saying how sorry I was about her husband’s diagnosis. “Holy Cross College isn’t paying your husband anything, right?”

“Right,” she said. “Nothing.”

“Let me talk to your husband.”

When she put him on the phone, I said, “OK, Dan, here’s what we’re going to do. I’m going to get a lawyer for you, so you can sue Holy Cross College for terminating you without giving you workers’ compensation for injury on the job. Is that all right with you?”

“Yes,” Dan said.

“OK, great. Mind if I talk to your wife again?”

When Laura came back on the line, I told her I was going to arrange for a colleague to work up the workers’ compensation claim. “Can you find out what exact product was used on that floor?”

“Sure,” she said. “I’ll talk to the maintenance guy. He has the stuff in the shed.”

Once I knew what the resurfacing product was, I obtained its material safety data sheet—an itemized list of chemicals it contains. I was shocked to discover that these chemicals included benzene, toluene and isocyanates, all of which are classified as ultrahazardous substances in Massachusetts.

Slowly and meticulously, I proceeded to build two lawsuits on behalf of Dan Allen. The first was against his employer, Holy Cross, seeking workers’ compensation because he had been injured on the job. The second was a lawsuit against the manufacturer of the resurfacing compound.

I arranged for a workers’ compensation expert to file a claim. Next, I contacted a dosing expert I knew at Harvard University, who calculated the chemical dose Dan had been exposed to. Based on our data—including the square footage of the area, the cubic feet of air in the space where the compound was applied, the location of Dan’s office, the doors and windows, and so on—we calculated the exact chemical dose Dan inhaled as a result of the floor resurfacing. We now had the right pieces in place to prove that Dan’s injury was caused by his exposure to the chemicals used in resurfacing the floor.

We knew Dan was in the building when the floor was being refinished with chemicals known to be neurotoxic—in fact, the floor refinishers were required by their employer and Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulations to wear respirators. They had sealed off the area where they were doing the work, but somehow Dan’s office, adjacent to the gymnasium, became part of the sealed area instead of being sealed off. He was therefore working without a respirator in the same area as the toxic chemicals.

Dr. Ratner told me that Dan’s initial symptoms—nausea, headaches, dizziness—made a great deal of sense to her.

“We have an area of our brain called the area postrema that alerts us to something poisonous,” she said. When toxic chemicals penetrate the nervous system, this part of the brain signals the body to get rid of it by triggering the vomiting reflex. “That’s one of the reasons why people inhaling these chemicals inside buildings report feeling nausea and vomiting as well as dizziness, headaches and other symptoms.”

Dan Allen became a wheelchair user whose family had to feed and bathe him. Photo courtesy of Alan Bell.

PROVING THE CONNECTION

Once Dr. Ratner diagnosed Dan Allen with ALS, and the dosing expert from Harvard had calculated the exact dose of the isocyanates and toluene Dan was exposed to, I recruited Dr. Mohamed Bahie Abou-Donia of Duke University, a world expert on isocyanates, as a medical expert on Dan’s legal case.

Dr. Abou-Donia had conducted research studies exposing mice to the same chemicals used in the flooring compound that caused Dan to fall ill. Like humans, some mice are born with a gene that predisposes them to developing ALS after exposure to certain chemicals.

The result? Basically, his studies

proved that mice with the gene developed ALS after chemical exposure, while the animals without the gene stayed healthy. Dr. Abou-Donia concluded that it wasn’t the coach’s fate to develop his fatal disease. Like Dr. Ratner and me, he believed that Dan’s exposure to isocyanates and toluene triggered his onset of ALS.

Like all diseases, whether you get ALS depends on a combination of your genetic predisposition toward the condition combined with environmental triggers, including chemical exposure. ALS usually affects older people, he explained. “Although you can see it in younger people in their 40s and 50s, it’s rare.” Dan was only in his mid-40s.

From November’s ABA Journal: Why toxic torts are hard to litigate and win.

“We know chemical exposure can alter the DNA of a human being,” Dr. Abou-Donia said, “and make people more susceptible to disease, causing upregulation and downregulation of many genes that cause disease.”

What does this mean in layman’s terms? Each of us begins life with a particular set of genes—about 20,000 to 25,000 of them. Scientists are gathering evidence proving pollutants and chemicals are altering our genes—not by mutating them but by sending signals that switch them on when they otherwise might remain dormant, or even silence the genes altogether.

Sidebar

Attorney Alan Bell prosecuted organized crime cases for Florida before developing multiple chemical sensitivity. He founded the Environmental Health Foundation, which advocates for victims of environmental injury. Bell lives in Capistrano Beach, California, and he focuses on toxic tort cases. Bell can be contacted at alanbell.me, and his book, Poisoned: How a Crime-Busting Prosecutor Turned His Medical Mystery into a Crusade for Environmental Victims, (Skyhorse Publishing) is available through Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Indiebound.