Nov. 25, 1933: 'Ulysses' goes on trial

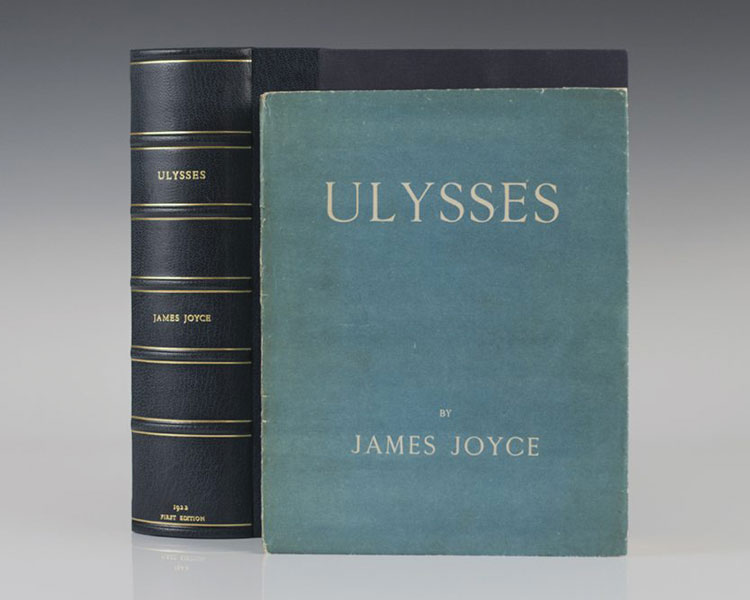

A first edition of "Ulysses" from 1922. Photos by Bettman/Getty Images.

Among the guardians of public morals at the start of the 20th century, none rivaled Anthony Comstock. As founder of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice in 1873, he spent his life rooting out anything and everything that smacked of sex.

Comstock was authorized as a U.S. postal inspector and a deputy sheriff. Armed with a federal law that bore his name, he seized pornographic pictures, closed brothels, patrolled saloons, boarded up bookstores and, by the time of his death in 1915, convicted more than 3,000 for violations of state and federal morals laws.

The Comstock Act was grounded in Great Britain’s Hicklin rule, a mid-19th-century declaration that obscenity should be defined by its potential to deprave the young or vulnerable. But as American society became more urban and modern, the moral regime behind the Comstock and Hicklin laws began to chafe against social reality and the imaginings of art.

At the epicenter of the modernist debate on both continents was Irish author James Joyce, whose growing body of short stories and novels refracted the grit and grace of working-class Dublin in a vernacular that rambled between lyric and crass. The boldness of his language, nested within interwoven interior narratives—a style dubbed “stream of consciousness”—gained regard as unmistakable genius and unrepentant smut.

Joyce’s artistic arc was marked by pursuit of a masterpiece, a novel that sought to replicate a specific day—June 16, 1904—in the lives of three characters, narrated through a vapor trail of unreliable memories and half-imagined intimacies. The novel, which became known as Ulysses, was epic in its sprawl and poetic in its purpose.

Behind Ulysses lurked a bohemian drama. Plagued by persistent poverty, virulent headaches and recurring blindness, Joyce spent more than 10 years producing, editing and reshaping chapters that were published individually in magazines in Europe and the United States. Each issue was considered a literary event—as well as a violation of the Comstock and Hicklin measures—precipitating an agonizing game of censor and mouse.

From their base in Paris, Joyce’s agents employed elaborate smuggling schemes to place Ulysses in the hands of readers. Censors on both sides of the Atlantic seized and burned thousands of copies of each iteration of Joyce’s master work.

This strange dance ended in May 1932, when civil liberties lawyer Morris Ernst dropped off a copy of Ulysses at a U.S. customs office, demanding that reluctant officials seize it. Ernst and Joyce’s American publisher, Bennett Cerf, had decided to confront the continuing censorship by creating a federal challenge under customs regulations in which the book would be prosecuted without criminal consequences.

Before U.S. v. One Book Called Ulysses, arguments regarding the First Amendment revolved around political speech. But postwar labor turbulence and the Great Depression had fused art and politics in ways courts were just beginning to address.

On Nov. 25, 1933, the case went before Judge John Woolsey, who had spent his summer reading Ulysses. He was perplexed and intrigued by a narrative style unlikely to attract the young and vulnerable souls protected by Comstock and Hicklin. When Ernst argued that Joyce’s intent was to replicate the meandering consciousness of everyday life—however mundane or obscene—Woolsey took his point.

He said to Ernst in open court that while listening to him, Woolsey was thinking about a Hepplewhite chair behind him.

In an extraordinarily revealing opinion about two weeks later, Woolsey wrote that he found the book to be more tragic than pornographic, “a sincere and serious attempt to devise a new literary method for the observation and description of mankind.” It did not “stir the sex impulses,” he said.

Endorsing the book’s legal entry into the United States, Woolsey wrote: “It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.”

Paris publisher and bookseller Syvia Beach and “Ulysses” author James Joyce.