Nov. 5, 1831: Nat Turner tried for slave rebellion

Photograph courtesy of Flickr creative commons

Moreover, vague reports of slave uprisings elsewhere in the hemisphere rattled slave states and their legislatures, already anxious about a rise in the rhetoric of Northern abolitionists. In a flurry of draconian legislation, Southern lawmakers passed laws forbidding most interaction between slaves and the free blacks or sympathetic whites who might excite them. Church meetings drew suspicion. Teaching slaves to read became punishable. And anything that presented itself as resistance to white authority, no matter how trivial, was dealt with harshly under color of law.

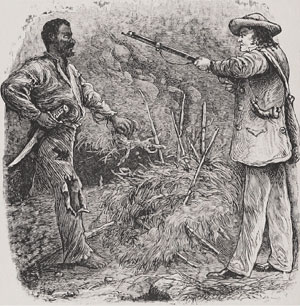

On the evening of Aug. 21, 1831, white fears were realized in Southampton County, Virginia, when scores of blacks, mostly slaves, began to storm in rebellion through white farms and plantations, wreaking mayhem in Tidewater towns. Over the next 40 hours, the slave revolt left at least 55 white people dead—men, women and children.

The slaughter ended with the capture of more than 48 slaves and freedmen. Dozens more of the rebels had been slain, many simply executed on the spot. Among those who eluded capture was Turner, the slave who had been their acknowledged leader. As army detachments searched for him, mobs and vigilantes joined in, exacting revenge against blacks—among them many innocents. Though a number of actual trials took place for those captured, reports of lynching and beheadings became commonplace across the Tidewater. By the time Turner was taken into custody on Oct. 30, an estimated 100 blacks in excess of those first captured had been killed.

Once in custody, Turner never denied his involvement. When Thomas Gray, a wealthy white lawyer and slave owner, interviewed him two days after his arrest, Turner was eloquent and unrepentant. He described the killings to Gray in as much detail as he could, saying his goal had been nothing more complicated than liberation. Given to spiritual revelations since childhood, Turner said he had been moved by a vision of “white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun was darkened.” The vision had been confirmed, he said, by a solar eclipse on Feb. 12. Unbowed, Turner declared: “I am here, loaded with chains, and willing to suffer the fate that awaits me.”

On Nov. 5, Turner stood trial in Jerusalem, a town he had hoped his small force would conquer. The trial lasted six hours, the centerpiece of which was his confession to Gray. The outcome was foregone. On Nov. 11, Turner was hanged. By all accounts, he met death calmly and quietly, his body barely moving when it reached the end of the rope.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.