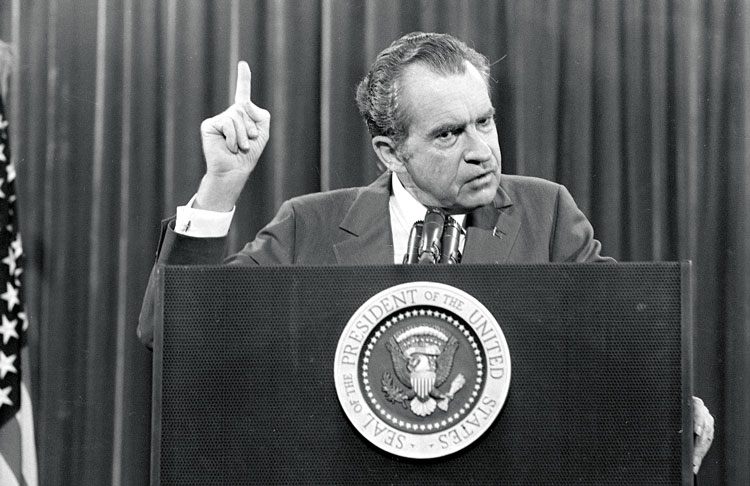

A new book looks at how a law firm stint revived Nixon's political and presidential prospects

Photo of Richard Nixon by AP Images

Pepsi’s photographer got numerous shots of Khrushchev drinking Pepsi-Cola. Obviously, the Soviet leader preferred the one with Russian water—and touted its superiority over the American version—calling it “quite refreshing.”

It may not have had the same cultural impact of Joanie Sommers singing “It’s Pepsi, for Those Who Think Young,” but it was no less effective. After all, in a totalitarian state like the Soviet Union, if the leader drank something, then everyone drank it. As such, Kendall was able to negotiate a 15-year exclusive deal with the USSR shortly after the expo ended—a deal that, effectively, shut Coke out of the Communist stronghold.

Kendall was grateful to Nixon for his role in making it happen. “We got front-page publicity all over the world: ‘Khrushchev learns to be sociable,’ ” he recalled. “The publicity was unbelievable. It saved my job.”

So when Nixon started job hunting in 1962, Kendall paid him back by giving him a very important chit to play with potential employers. He made it known that whichever firm hired Nixon would also get Pepsi, with its annual legal billings in excess of $3 million, as a client.

Pepsi wasn’t the only client Nixon brought with him. Several from a previous stint at Adams, Duque & Hazeltine in California after the 1960 election followed him to the Big Apple, including Jessop Steel, Dreyfus Corp., Richfield Oil, Precision Valve Corp. and Virginia Industries. Nixon also proved adept at signing up new clients, including shipping magnate Daniel Ludwig, one of the richest men in the world, and banknote manufacturers Thomas De La Rue Inc. The latter also gave him a seat on its board, and chairman Francis Sorg recalled that Nixon “did no legal work at all. … With us, he was not going to be a lawyer; he was going to be a salesman.”

EL JEFE

AP Images.

On several politically sensitive matters that his firm was involved with, including a potential representation of controversial Vietnamese political figure Tran Le Xuân, better known as Madame Nhu, Nixon was content to keep a low profile. On one matter, however, he was more than happy to be out in front, even if his actual involvement was somewhat limited.

On May 30, 1961, longtime Dominican Republic strongman Rafael Trujillo’s car was ambushed by several gunmen while the “First Teacher, First Doctor, First Journalist of the Republic” was executed gangland style as he was being chauffeured home. The assassins wielded American-style M1 carbines, leading to the conclusion that the CIA had Trujillo killed.

That theory didn’t hold much water—especially coming on the heels of the Bay of Pigs debacle. The last thing the Kennedy administration wanted was to take out an anti-Communist leader like Trujillo and leave a power vacuum for a Dominican Fidel Castro to fill. Indeed, declassified CIA documents indicate the agency wasn’t directly involved but almost certainly had foreknowledge of it and had provided the guns used by the assassins.

With most long-term dictators, the safe assumption is that they have a fortune squirreled away in a country with secretive banking laws. Trujillo was no different, as he was rumored to have a personal wealth of nearly $500 million, with over $180 million stashed in a Swiss bank account. The sheer enormity of such a fortune guaranteed that it would serve as a battleground for the various Trujillo heirs, who all wanted a piece of the late strongman’s estate.

What made this battle even more complicated came down to the other dictatorial cliché that Trujillo had more than lived up to. “Lover of Dominican Women” had not been one of his extravagant titles, but it probably could have been. Trujillo had many, many mistresses and girlfriends, and as a result, he had many, many illegitimate children. (It’s never been definitely proven how many he had.) Given the reputed size of his fortune, it was inevitable that Trujillo’s death would trigger a veritable battle royale for his riches

In July 1964, the Los Angeles Times reported that a group of six illegitimate children had hired Nixon and his firm to represent them as they tried to collect their portion of the estate. Nixon’s clients were based in Miami and had named the Miami Beach First National Bank as their trustee.

Nixon got the publicity, but how much work he actually did on the case is in dispute. Raymond Steckel, an associate in the Paris office of Nixon Mudge, recalled that the case belonged to Nixon’s partner Randolph Guthrie, who had a relationship with the chairman of the Miami bank

“I have no recollection of Nixon working on the case,” said Steckel. In fact, a December 1965 message from Nixon secretary Rose Mary Woods to Nixon seemed to confirm this, as Woods relayed a message from John Davis Lodge, former ambassador to Spain, urgently requesting briefing materials for an expert Lodge wanted to weigh in on the matter.

“I explained that this was not your case—that this material would have to come from Mr. Guthrie since this was his case—NOT YOURS,” Woods wrote to Nixon.

The firm, on behalf of the Miami-based children, filed a criminal complaint in Geneva accusing Trujillo’s son Radames of misappropriating his late father’s millions. Radames, who was living in exile in France, was accused of stealing $150 million from his dad’s coffers and was extradited to Switzerland in November 1964 to face the charges. The Miami heirs claimed that, because of Radames’ theft, there was less than $6 million left in the account. Ultimately, Nixon Mudge reached a settlement with Radames (the terms were not disclosed), and he was released from Swiss custody.

However, there were other fish for the Miami heirs to fry. At one point the lawyers looked at whether or not to file a case in Santo Domingo, and Steckel recalled flying into the Dominican Republic’s capital to explore that possibility. The post-Trujillo years were highly unstable, with multiple revolutions and coups d’état taking place before the United States forcibly intervened in 1965. It was during one of these revolutionary periods when Steckel flew down to the country. “I could still hear guns going off in the background,” he recalled. “It was exciting but also scary.” He met with the newly appointed minister of justice and asked to copy some files relevant to the Trujillo matter.

“I show up, me in my little lawyer suit, and here’s this rather burly fellow in his early 40s wearing a short-sleeve white shirt,” Steckel said. “He asked me to sit down and then started explaining why I couldn’t actually copy the files. Before I could say anything, he pulled open his right desk drawer and pulled out a .45 and put it on his desk. He didn’t say another word.”

Ultimately, Steckel said, he was allowed to look at the files and copy what he could by hand. “So, when the Miami bank suggested filing an action in Santo Domingo, I told them that, based on what little I knew about civil law in the Dominican Republic, pursuing this claim in the middle of a revolution didn’t strike me as a very useful thing!”

Nixon in New York, published in April by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, is the first book written by Victor Li, an assistant managing editor at the ABA Journal. A former prosecutor in the Bronx, Li came to the Journal as a reporter in 2013 after stints with Law Technology News, The American Lawyer and Litigation Daily.

This article was published in the May 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Nixon in New York: A new book looks at how a law firm stint revived his political and presidential prospects."