A new book looks at how a law firm stint revived Nixon's political and presidential prospects

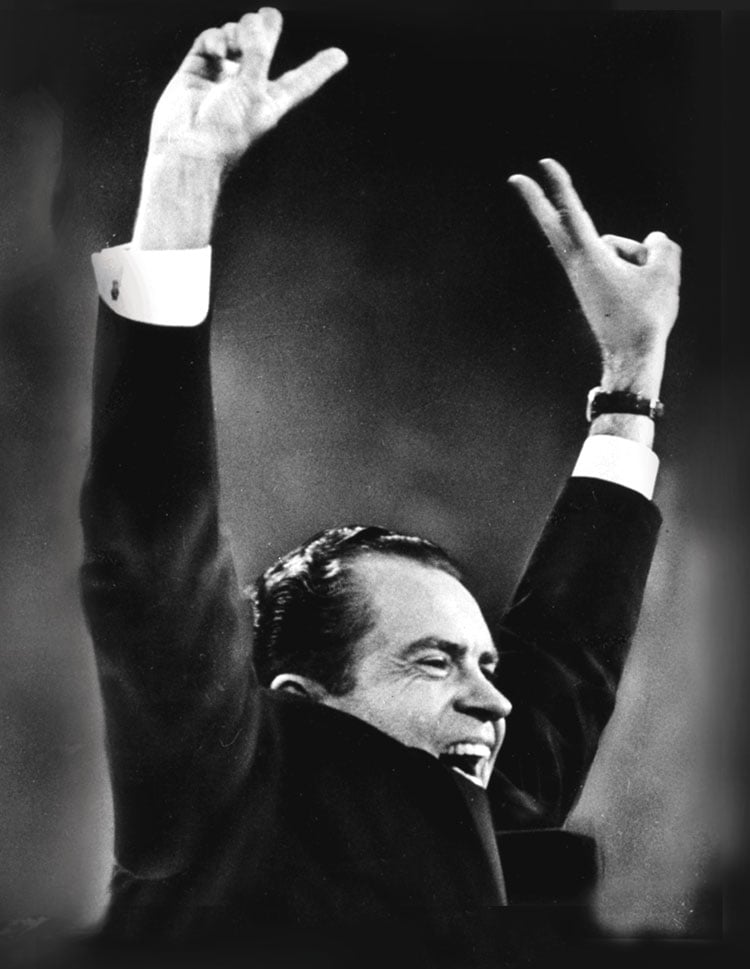

Photograph of Richard Nixon by Associated Press.

The inspiration for Nixon in New York: How Wall Street Helped Richard Nixon Win the White House came out of a story idea I had to interview people who worked with Nixon at his New York City-based law firm, Nixon, Mudge, Rose, Guthrie & Alexander, on the 50th anniversary of his joining in 1963. That article didn’t go forward, but the idea for the book remained stuck in my head. This edited excerpt looks at how Nixon’s role as public partner at the firm was the ideal platform as he looked to reinvent himself after election losses in 1960 and ’62. Having his own firm gave Nixon access to deep-pocketed clients, allowed him to travel internationally and burnish his foreign policy credentials and, most importantly, helped build a formidable staff of top-notch lawyers, researchers and writers—a staff that did just about everything for him when it came time to ramp up for the 1968 campaign.

During his first meeting with Richard Nixon, Leonard Garment recalled, his senior partner was pretty clear about his vision for the firm. “He thought that what was right for him would also be good for the firm,” Garment said.

The latter part of that statement came true almost immediately: Nixon proved to be every bit the client magnet he had promised to be. Business boomed at Nixon Mudge almost from the moment he joined.

According to an accounting report prepared by Arthur Young & Co., the firm collected $2.6 million in fees in 1963 (Nixon joined in August of that year and became partner in January 1964). That number shot up to nearly $3.5 million the following year before creeping up toward $3.8 million in 1965. (The $2.6 million in fees from 1963 translates to over $21 million in 2018 dollars based on the CPI Inflation Calculator from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Likewise, the $3.5 million from 1964 is roughly equivalent to $28 million in 2018, while $3.8 million becomes more than $30 million.)

See our gallery: Nixon in New York

A lot of work came into the firm during that time, as Price Waterhouse & Co. found when it conducted a survey of various law firms in the country. In 1963, firm partners billed an average of 857 hours each, a decrease from 1962, when partners billed 929 hours each. In 1964, however, average partner billable hours shot up to 1,119 hours and hit 1,251 the following year. Nixon Mudge associates were likewise busy, seeing their average hours shoot up during that three-year span from approximately 1,500 hours a year to over 1,700.

Richard Milhous Nixon bounced back from election defeats by parlaying his legal career in New York City into a platform for the 1968 election, which he won as the Republican candidate. Photograph by Getty Images.

As a result of this increase in business, Nixon’s partners at the firm saw their bank accounts swell. According to a Price Waterhouse study, average operating income per partner increased from $46,150 in 1963 to $68,110 in 1964. The study, which compared Nixon Mudge to a group of 49 large firms in the United States, ranked Nixon’s firm 42nd in 1963 when it came to average operating income per partner. A year later, they were up to 26th. After 1965, the average operating income per partner increased further, going up to $73,500. (The $73,500 in 1965 translates to over $586,000 in 2018 dollars.)

Nixon’s arrival also led to an expansion at the firm. In 1963, the same year Nixon came aboard, the firm acquired Dorr, Hand, Whittaker & Watson, a smaller firm on Wall Street that specialized in railroad law. With Nixon in tow, the firm anticipated an uptick in government-related work. As such, the following year, Nixon Mudge acquired a two-partner maritime law firm in Washington, D.C., named Becker & Greenwald. The main office, at 20 Broad St. in Manhattan, also expanded considerably, as the firm hired so many additional lawyers and employees that it went from three floors in 1962 to five by the start of 1967.

Nixon was hardly the only rainmaker at the firm, but he quickly established himself as one of the most effective. Almost immediately after his arrival, several of the firm’s existing clients, like automaker Studebaker and longtime Nixon friend Elmer Bobst’s Warner-Lambert Co., started sending most of their work to Nixon Mudge.

Nixon also proved highly adept at bringing in new clients. “For the young lawyers that wonder how business is gotten—it isn’t done always directly,” Nixon said. “It’s a matter of fact the most effective way is indirectly.”

For instance, he recounted that he would often go to dinner parties, meetings and other social events with prospective clients, and he would never bring up business or legal representation. “As time goes on—when they need representation or when they want to change their representation—they will think of you,” Nixon said. “In all the time I was with either [previous firm] Adams Duque or [Nixon Mudge], I have never asked anybody for business, never. And I think that’s the most effective way to do it.”

In private, Nixon was far less charitable. “I never realized how easy it is to make money,” he said. “I just got $25,000 for telling a bunch of stupid jerks something they could have learned from the newspapers.”

As one partner explained to legal journalist Paul Hoffman, corporate executives have “an almost childlike enthusiasm for celebrities,” and Nixon was one of the biggest. Some of them simply wanted to be able to brag: “You remember my lawyer, Dick Nixon, don’t you?”

‘IT SAVED MY JOB’

Photograph of Richard Nixon by Getty Images.

Long before Pepsi had the likes of Michael Jackson, Madonna or Shaq as a celebrity endorser, it had Nikita Khrushchev and Richard Milhous Nixon. Their commercial for Pepsi didn’t include pyrotechnics, choreographed dancing, catchy jingles or sex appeal—unless you consider a debate over the merits of capitalism versus communism between the vice president of the United States and the premier of the Soviet Union sexy.

In 1959, Nixon was visiting Moscow when he and Soviet leader Khrushchev made a joint appearance at the American National Exhibition at Sokolniki Park. The exhibition was held to promote cultural understanding between Russians and Americans, but the two leaders took the opportunity to engage in an impromptu debate that started inside the kitchen of an American-style display house and continued all over the showroom floor, with the two men gesticulating and jabbing fingers at each other while reporters and photographers recorded everything. When they got to the Pepsi-Cola stand (which featured two different Pepsi drinks: one made in the United States and one made with Russian water), that’s when it happened.

-

The company’s new slogan was “Be Sociable! Have a Pepsi!” What better ad than a picture of American’s foremost adversary (and the scourge of Coca-Cola, which the party in Europe equated with capitalist decadence) acting sociable over a Pepsi made in the USSR? [excerpt from As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s by Karal Ann Marling]

“Don’t worry about it, Don,” Nixon is said to have told Pepsi’s CEO, Donald Kendall. “I’ll bring Khrushchev by and we’ll get a Pepsi in his hand.”

Nixon in New York, published in April by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, is the first book written by Victor Li, an assistant managing editor at the ABA Journal. A former prosecutor in the Bronx, Li came to the Journal as a reporter in 2013 after stints with Law Technology News, The American Lawyer and Litigation Daily.

This article was published in the May 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Nixon in New York: A new book looks at how a law firm stint revived his political and presidential prospects."