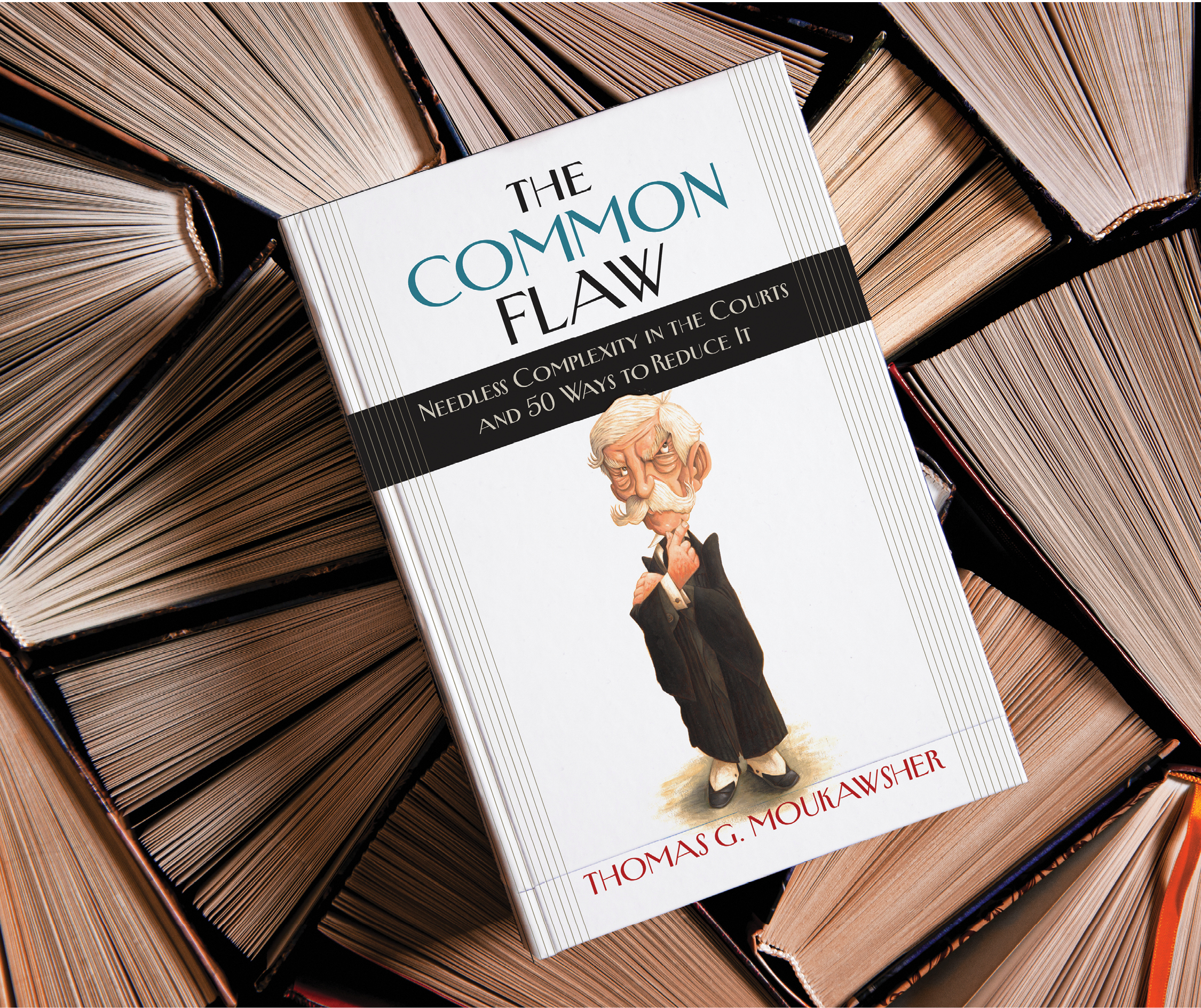

Needless complexity in the courts and 50 ways to reduce it

Shutterstock

Thomas G. Moukawsher had a folder on his computer labeled “stuff to fix.” But it didn’t include the loose step in the attic or the squeak in the screen door.

His tasks were more ambitious: dramatically change how complaints are drafted; question the number of motions in limine; rethink using experts for matters of common sense; and countless other projects designed to address deficiencies in civil litigation.

Moukawsher’s ideas were the product of his more than 10 years of adjudicating as a judge on the Connecticut Superior Court—with the bulk of those cases being complex civil disputes. He retired in October.

It was a “cumulative process,” Moukawsher says of the development of his to-do list, starting with “little notes.” But when COVID-19 hit, he had more time to reflect and decided to expand it.

Just before stepping down, Moukawsher, 61, published The Common Flaw: Needless Complexity in the Courts and 50 Ways to Reduce It. He left behind a playbook for others to tackle his stuff to fix.

Moukawsher admits his guide “gets pretty far down in the weeds.” But there’s good reason. It is the weeds, he says, “that are choking the litigation-centered humanity out of courts—with snarled complaints, tangled motion practice, choking discovery, smothering trials and stultifying legal rulings.”

‘What is it you want?’

As all know, the vast number of civil cases end without a trial.

“Many are settled unsatisfactorily,” Moukawsher says, “because the parties would rather be unhappy than broke. They would rather be dissatisfied with the courts than pay the crushing cost of maneuvering around the procedural obstacles between them and trial.”

Moukawsher lays much of the blame for this failure of the civil justice system at the feet of “punishing discovery.”

It is a process he amusingly describes in his book as a cat laying out a maze to chase a mouse through the use of interrogatories and document production requests.

Months, or even a year or two later, “the cat will get the cheese—most of it, anyway.”

The former jurist’s solution to this Tom and Jerry routine was judicial involvement from the outset. At the first scheduling conference, he would ask the plaintiff: “What is it you want?” Oftentimes, he says, “it is a limited universe—to start with, anyway—of documents.”

Moukawsher would then set out the sought-after discovery in a court order. The impact was dramatic.

“Nobody is going to turn around when I put it in a court order, and say, ‘I don’t understand what ‘is’ is here. … I’m going to write back to you and object. I don’t know what you’re asking for.’”

“When a judge makes an order about discovery, you don’t get that,” he says. “They follow the order and actually turn over the documents.”

If problems arose, Moukawsher would jump into the scrum.

“Write to my clerk,” he would tell bickering lawyers, “and the next day you’ll be on the video screen with me, and I’ll get you another order.”

Moukawsher first witnessed this hands-on approach to discovery in his ERISA cases before California U.S. District Judge William Alsup back when he was a leading employee benefits lawyer.

“My god, this is wonderful,” Moukawsher recalls thinking of his time before the jurist. “He resolves it immediately.”

Streamline trials

Moukawsher’s time on the bench produced a host of fixes to streamline trials. He speaks enthusiastically about the time that can be saved by the use of admissions.

“Most trials today are about proving undisputed matters,” the former jurist opines. “Give me a list of stipulated facts.”

Moukawsher says admissions are particularly useful for dealing with the “pallets of exhibits” that a trial produces. For example, he describes the tedious process of a lawyer introducing reams of bank records when the parties could simply stipulate that “the bank account showed x dollars on a certain date and y dollars on another date.”

Moukawsher also favors the use of a time clock at trial. He points to Parkinson’s Law—work expands to fill the time allotted to it—for the need for the timer.

“If lawyers have no endpoint for a trial,” he says, “it drags.”

Each side is allocated a certain number of minutes. When a lawyer speaks, including to object, the clerk starts the clock. The process, Moukawsher says, can result in fewer frivolous objections, only necessary witnesses being called and counsel stipulating to facts and exhibits.

The bigger picture

While many of Moukawsher’s solutions are granular, he also has a wider message.

“When courts strain and expand basic questions”—such as standing, statute of limitations, jurisdiction, ripeness and staleness—they are “exalting form over substance.”

By focusing on “increasingly complex mechanics,” Moukawsher says, too many cases are resolved “without ever answering the actual questions the parties raised.” The result: “People walk out of the courtroom feeling that they and their problem have not been heard.”

Moukawsher advocates for what he calls a “humanist lawsuit,” one that is about the people involved and their conflict. It is resolved by a decision and not the parties’ exhaustion.

But the judicial veteran is not Pollyannaish. He is aware that he is swimming against the tide—trying to change a system that thrives on the principle that things are done a certain way because that’s the way they’ve always been done.

“The hope is that one person at a time will get some ideas from it. Maybe a few things catch on.”

This story was originally published in the December 2023-January 2024 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “The Common Flaw: Needless complexity in the courts and 50 ways to reduce it.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.