Municipal ordinances can banish low-level offenders for petty offenses

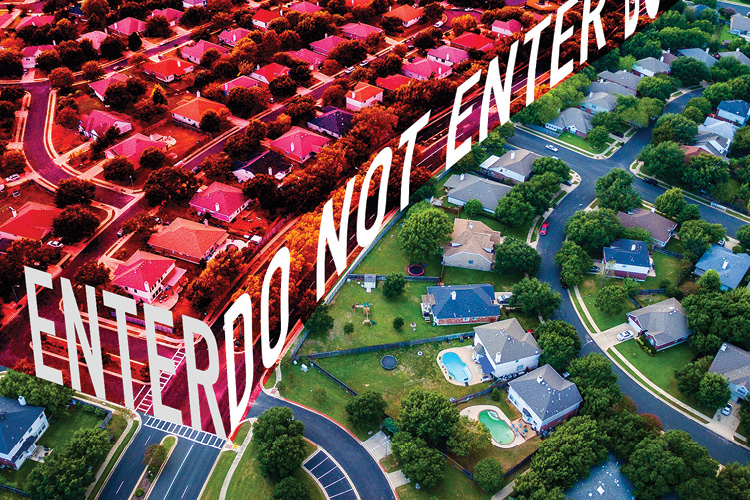

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, civil litigation attorney Maureen Hanlon waded into St. Louis Municipal Court on behalf of a jail inmate.

He was a homeless man who originally fell afoul of the law for trespassing on private property. Because he broke a court agreement to stay out of the downtown area, Matthew Maufas found himself serving a 120-day jail sentence.

Hanlon’s legal advocacy organization, ArchCity Defenders Inc., got wind of Maufas’ case in early 2020 as COVID-19 was beginning to hit incarcerated populations. It had due process concerns about the way he had been treated. Hanlon says Maufas was without legal counsel when city attorneys offered him a “Neighborhood Order of Protection” as part of a probation agreement.

“My client didn’t really remember signing it, he wasn’t aware of the provisions of it, he didn’t understand the implications of it,” Hanlon says.

In response to her motion, a city judge set aside her client’s guilty plea and sentence, and her organization found social services for Maufas, who has schizoaffective disorder.

St. Louis began implementing “NOPs” in 2003 as a way to scatter drug offenders, but elected leaders amended and expanded the ordinance in 2005.

According to the revised code: “A Neighborhood Protection Order is any court order that prohibits a person from being in any specified area as a condition of release from custody, a condition of probation, parole or other supervision or any court order in any criminal matter.”

Although St. Louis is not the only U.S. city with an exclusion law for low-level offenders, critics say these types of measures raise constitutional concerns and result in sending troubled people elsewhere—often within the same municipality—while acute social problems are ignored. Proponents of the laws say they help deter illegal activity.

“There’s going to be some aspect of ‘whack-a-mole,’ where they leave one area and they move to another part of the city,” concedes Hil Kaman, an assistant city attorney in Everett, Washington, speaking about his city’s ordinance banning drug offenders from certain areas.

But law-abiding citizens should not have to tolerate repeated criminal activity, Kaman says, and in Everett, addicts are seen smoking fentanyl in plain view.

“We get a lot of feedback from local businesses and residents when it gets out of control in a particular area,” he adds.

Ordinance efficacy

Legal observers say under exclusion measures, punishments can balloon dramatically for low-level offenders within opaque municipal court systems.

“These ordinances raise a host of equity and justice issues and may not even achieve their intended purposes of preventing crime,” says Sarah Adams- Schoen, an assistant professor at the University of Oregon School of Law and a council member of the ABA State and Local Government Law Section.

“The exclusion ordinances can be and are used to target certain people—including unhoused people, people of color and other historically marginalized people—for harsh treatment,” she adds. “There are few procedural protections and also the potential that the initial civil violation order will ratchet up to a criminal violation.”

The American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois made similar objections in 2018 when the Chicago suburb of Elgin was revisiting an ordinance creating “Public Nuisance-Free Zones” within the city’s central business district and public parks.

Under Elgin’s ordinance, a person can be deemed a “public nuisance offender” if they commit three offenses—ranging from low-level felonies like theft to city infractions such as public intoxication, disorderly conduct or vandalism—within a 12-month period. The “civil exclusion” period for first-time offenders can last up to 90 days.

Exceptions can be granted for people who need permission to go to particular locations, such as their residence, social service agency or an attorney’s office. Violators can be fined up to $1,000 or jailed for up to 30 days. According to the code, a judge or administrative hearing officer can extend the exclusion period for an additional six months for a trespasser.

Ten people were determined to be nuisance offenders in 2020, the Elgin Police Department reported.

Civil exclusion ordinances “provide police and government with too much power to move people from locations in the community, not because they have committed a crime but simply because they are poor or are experiencing homelessness,” says Ed Yohnka, director of communications for the ACLU of Illinois.

While police department stats indicate reductions in designated public nuisance offenders over the last three years, Yohnka says his organization was unable to get enough data from Elgin to assess the effects of the ordinance. Elected leaders and top city administrators did not respond to ABA Journal interview requests.

A lack of transparency can be a hallmark of municipal governments that use exclusionary tactics, says Katherine Beckett, a University of Washington professor of sociology and law, societies and justice, and co-author of Banished: The New Social Control In Urban America.

Beckett and her colleague Steve Herbert examined several exclusion- zone measures Seattle employed more than a decade ago, ostensibly to tamp down criminal activity.

Under one policy known as “trespass admonishment,” police officers ticketed and removed people from private properties such as businesses and parking lots.

“There was no city council vote on this,” says Beckett, who understands the policy was discontinued. “It must have derived from some interpretation of executive power.”

Exclusion ordinances have replaced the broader anti-vagrancy and anti- loitering laws that late-20th century courts declared unconstitutional. These ordinances effectively allowed police to roust anyone who looked out of place, according to Banished.

Sometimes, the newer ordinances have been used in hopes of breaking up illegal drug activity. Everett issues “Stay Out of Drug Areas” orders barring people accused of drug crimes from certain neighborhoods for up to two years as part of pretrial release or probation agreements.

Violations can result in jail sentences, but Kaman says the system has due process guardrails for suspects before they sign the agreements, including access to public defenders and the ability to request exceptions within the exclusion orders.

At least every two years, city council members review the list of neighborhood areas defined as having high levels of drug trafficking (currently eight). Last year, the Everett Municipal Court issued 103 orders under the law, according to city officials.

Legal challenges

The ordinance withstood a state-level legal challenge in 2008. In Everett v. Williams, a probationary drug offender claimed her Stay Out of Drug Areas order violated her constitutional “fundamental right to travel.”

The Snohomish County Superior Court disagreed, saying she had the ability to request exceptions to the order, and the restrictions contributed “toward the defendant’s rehabilitation and public safety.”

In contrast, the Cincinnati-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 2002 affirmed a lower court ruling against Cincinnati for the way that city issued 90-day exclusion orders for drug crimes. In Johnson v. City of Cincinnati, the ACLU of Ohio sued on behalf of a grandmother accused of a drug offense who could not visit her grandchildren, and on behalf of a homeless man who said he could not access social services in what had become an exclusion zone for him.

The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio had ruled against the city in 2000, citing the code as unconstitutional for violating fundamental rights of freedom of association and freedom of movement.

As for Everett’s approach to illegal drugs, it is not all punishment, says Kaman, who was the city’s public health and safety director from 2016 to 2018. The city also offers a variety of social services and diversion programs, but, he adds, “It’s very hard to get somebody to transition from the life of street drugs to a stable situation.”

Back in the Midwest, St. Louis has not issued any new Neighborhood Orders of Protection since in-person hearings were discontinued because of COVID-19 concerns in spring 2020, according to a spokesperson for Missouri’s 22nd Judicial Circuit (court officials did not provide data or records).

St. Louis Board of Aldermen President Megan Green said she planned to reintroduce legislation to keep homeless people from being impacted by the exclusion rules.

When she introduced the measure in 2017, some colleagues pushed back with concerns it would lead to neighborhood deterioration.

“Personally, I don’t think it’s an either/or,” Green says. “I think we can protect peoples’ rights and ensure that we have vibrant neighborhoods.”

This story was originally published in the June-July 2023 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Forbidden Zones: Municipal ordinances can banish low-level offenders for petty offenses.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.