Miranda in translation: ABA pilot project tests tools to help police deliver effective Miranda warnings in Spanish

Shutterstock.com

The Miranda warning is given in Spanish about 900,000 times every year, and a similar number of bilingual speakers would prefer being read their rights in Spanish, according to ABA findings.

Yet during preparations for the 50th anniversary of Miranda v. Arizona in 2016, members of the ABA Commission on Hispanic Rights & Responsibilities realized there was no universal Spanish translation of Miranda in the United States.

Richard Pena, chair of the ABA Commission on Hispanic Rights & Responsibilities. Photo courtesy of Richard Pena.

This realization was “like someone throwing a cold bucket of water over us,” said Richard Pena, chair of the commission, at the 2018 ABA Annual Meeting in Chicago. “It was startling.”

In response, the ABA House of Delegates passed Resolution 110 in 2016 calling for “federal, state, local and territorial law-enforcement authorities to provide a culturally, substantively and accurate translation of the Miranda warning in Spanish.”

It also led to the launch of a pilot program by the ABA, the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design and the New Orleans Police Department to develop a standardized Spanish-language Miranda warning that can be delivered by police officers in the field regardless of an officer’s language skills.

LOST IN TRANSLATION

Spanish translations vary because of the difference in dialects across Spanish-speaking communities in the United States and because of the confederated nature of America’s estimated 18,000 law enforcement agencies. In English, there are more than 800 versions of Miranda used in the United States, according to research by Richard Rogers, a psychology professor at the University of North Texas.

Finding a good translation of Miranda is not a new problem. Courts have been grappling with poor and incorrect translations since the 1970s.

Janet Jackson, director of the ABA Center for Innovation. Photo courtesy of Janet Jackson.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at San Francisco and the U.S. District Court for the District of Nebraska dealt with Miranda warnings that used the Spanish word puede, which means “could,” “may” or “can.” This changed the warning to “a lawyer may be appointed” as opposed to communicating the guaranteed right to a lawyer in a criminal trial.

In 1993, the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon confronted a version of Miranda that told a suspect they had the “right to interrupt the conversation at any moment.”

In other instances, an officer’s use of Spanglish—a nonofficial amalgamation of Spanish and English—led to Miranda warnings with words not found in Spanish dictionaries.

FORGING TOOLS

With the new set of tools developed by the ABA and its partners, there is a tempered hope that errors will be less common.

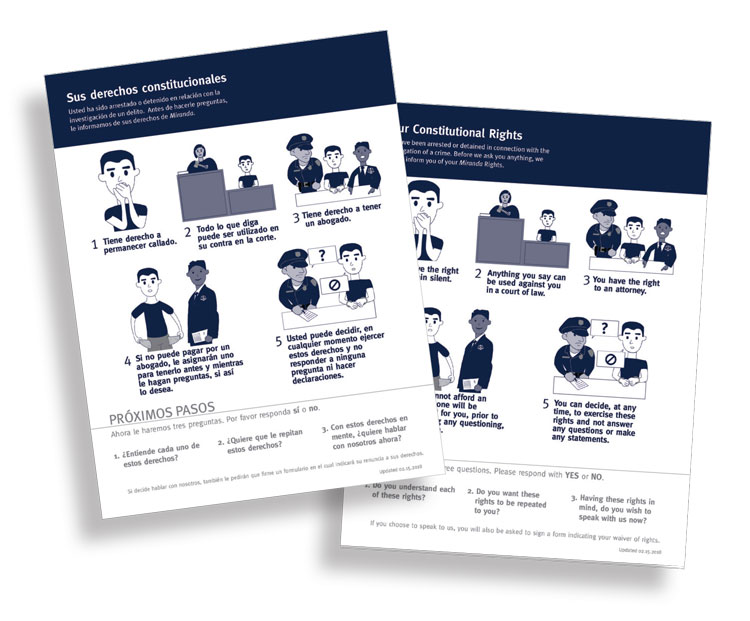

The Miranda Warnings Project team developed a laminated card with a small speaker—like a talking greeting card—and a web-based video called Sit & Watch Miranda that can be viewed on a squad car’s computer, said Moire Corcoran, a student at the IIT Institute of Design and project design team leader.

With audio icons and written text, the layered approach for both tools is “meant to reinforce comprehension,” she said during the Miranda Warnings Project panel at the 2018 ABA Annual Meeting in Chicago.

The low-tech, laminated cards also were built with recording in mind. The warning is written on both sides of the card, allowing the officer’s body camera to memorialize the event, said Jeremy Alexis during the meeting. Alexis is a senior lecturer at the IIT Institute of Design.

“They created something so innovative for our department,” said Cmdr. Otha Sandifer of the New Orleans Police Department. “For far too long, we gave the officers the card and a little bit of a training and hoped they would pronounce the words correctly when they were out in the field.”

Photo courtesy of IIT Institute of Design

Earlier this year, his department undertook a 45-day pilot with six of the new laminated cards, which cost a few dollars to make, spread out through the city. The results of the pilot are not yet public, but Janet Jackson, director of the ABA Center for Innovation, says the next phase is to test the cards and the video departmentwide. During this phase, she says, a way to measure suspects’ comprehension will be developed.

This project brought together a coalition of criminal justice stakeholders, leaving even the public defenders pleased, despite needing convincing.

“I was skeptical,” says Danny Engelberg, chief of trials at the Orleans Public Defenders. However, he came around to the project and says one way it improved current practice is “it slows down and clearly takes things step by step” through an audible and a visual presentation.

“This project gets us one step closer to someone having a chance of understanding and making an informed decision,” he says. Even with these improvements, “I still think there’s a lot of hurdles to get over to make sure someone is truly making an informed decision to waive their rights.”

CLEAR COMMUNICATION

Andrew Ferguson, a professor at the University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law, has written at length about digitizing Miranda. He met with the ABA team early on to talk about the project.

Photo of Andrew Ferguson by Andrew Ferguson

Ferguson is supportive of the ABA tools and is developing his own app that he hopes will overcome the root problems he sees with Miranda warnings.

“I don’t think that mere translation will do enough to really deal with contextual understanding problems that everyone faces,” he says. “Most suspects don’t understand their Fifth Amendment rights, and Miranda warnings do a poor job of explaining that.”

With many suspects chemically impaired or afflicted with a mental illness, he says there should be ways to make sure the warning is being understood and not just treated as a perfunctory constitutional requirement.

While Ferguson’s app is not developed yet, based on a paper he wrote in 2017 with Richard Leo, a professor at the University of San Francisco School of Law, it will likely ask questions of the suspect to gauge comprehension as the warning is given. If the app is on a device with a camera, the tool also can capture the person’s face, noting if a person seems impaired, for example.

While still new, the Miranda Warnings Project has been demonstrated for law enforcement from other jurisdictions with great interest, according to members of the panel. Even with that excitement, the chair of the ABA Commission on Hispanic Rights & Responsibilities offered a grain of salt. “To be honest, we don’t know where this is going to lead. We don’t know the ultimate impact,” Pena said. “We can say it has tremendous potential. It’s a no-brainer.”