Millennial lawyers are forging their own paths—and it's wrong to call them lazy

MYTH NO. 3: THEY ARE DISLOYAL AND JOB HUNTERS

Beyond solving long-standing problems through technology, millennials are also deeply committed to finding work that aligns with their values. Rikleen points to a 2012 study conducted at Rutgers University in which nearly 60 percent of young adults said they’d give up 15 percent of their salary to work for an organization whose values they share. Across the country, many young lawyers are rearranging their careers to accommodate more pro bono work.

This millennial tendency to pursue work that aligns with their values dovetails with another persistent myth, Blank says: That millennials are less loyal than other generations. “The reality is that we’re not—it’s conditional loyalty. There’s certain things we’re looking for, and one of those things is purpose. If we don’t see a company that really aligns with our values, we’re not going to stick around.”

Michelle Stilwell (left): “We care so much, and we’re totally dedicated to figuring out how to help out clients.” Photograph courtesy of Stilwell & Slatton Immigration.

Michelle Stilwell and Victoria Slatton, who became friends at Pepperdine University School of Law, know that feeling well. When President Donald Trump signed an executive order barring immigrants from seven largely Muslim countries, Slatton knew her job as an asylum officer at the Department of Homeland Security didn’t align with her values any longer. So even though they were less than two years out of school, she and Stilwell decided to launch their own Washington, D.C., firm, helping noncitizens tackle legal issues related to the immigration ban. Trump’s election and immigration policies were wake-up calls, Slatton says. And though they’ve confronted plenty of skepticism about how two 20-something lawyers can handle such thorny, politically charged cases, the pair say their passion—combined with social media savviness—has made up for inexperience. “We care so much, and we’re totally dedicated to figuring out how to help out clients,” Stilwell says.

Jessie Kornberg: “People like to complain that millennials don’t stick around in one spot long enough. I’m trying to reshape that idea.” Photograph courtesy of Bet Tzedek.

Jessie Kornberg felt a similar call to action. After graduating from the UCLA School of Law, the San Francisco Bay Area native worked at Bird Marella, a Los Angeles boutique litigation firm. In 2014, she was appointed the first female CEO of Bet Tzedek, a 60-employee nonprofit that has provided free legal service to people in Los Angeles for more than four decades. Under Kornberg’s leadership, the agency has created the county’s first transgender medical-legal partnership, a small-business startup clinic and a program to respond to growing concerns around the deportation of undocumented immigrants.

Although she studied ballet seriously as a child and worked for a New York City nonprofit that provided after-school programming following graduation from Columbia University, Kornberg has known she wanted to be an attorney since fifth grade, when she learned that Thomas Jefferson was a lawyer. At Bet Tzedek, Kornberg oversees $15 million worth of annual legal services to low-income, disabled and elderly people in an increasingly challenging environment. While she acknowledges rising anxiety about new threats and deportation surges that affect her clients, “I’m constantly inspired by the energy with which my staff is responding to it,” she says. “We’re on track to serve four times as many people this year as last, and that is a direct result of the terror being created in our immigrant community. It is both maddening and motivating.”

Kornberg gives credit to mentors who helped her immensely in her early days as Bet Tzedek’s youngest chief. “There’s no way to talk about my career without focusing on key relationships,” she says. “People like to complain that millennials don’t stick around in one spot long enough. I’m trying to reshape that idea, because I think it’s amazing that we hop around like fleas. It means that so many different entities can be connected through colleagues.”

MYTH NO. 4: THEY’RE TOO DIFFERENT FROM PREVIOUS GENERATIONS

Nicole Abboud: “The whole point of my podcast was to make it inspirational and show lawyers that you don’t have to feel stuck. I feel lucky every day to reach people.” Photograph courtesy of The Gen Why Lawyer.

Nicole Abboud also owes her career to the relationships she forged early in her law practice. After graduating from Southwestern Law School, she tried her hand at several different kinds of law, from family to intellectual property. But after planning to be a lawyer her entire life, “when I started practicing, I realized I didn’t love it,” she remembers. In an effort to define her future and break out from the disillusionment and isolation that came with professional dissatisfaction, Abboud began asking other young lawyers about their own stories. She eventually created the Gen Why Lawyer podcast, which focuses on millennial attorneys who either redefined their law career in a way that increased their satisfaction or left law altogether. “I had no experience whatsoever—I looked up free YouTube videos about what podcasting equipment to buy and how to record and upload to iTunes,” says Abboud of Culver City, California. Her initiative paid off, and Gen Why’s success led her to leave her law job to launch a video and podcasting business, Abboud Media, to help lawyers develop their personal brands.

“To be honest, I struggled a lot with an identity crisis when I left the law,” Abboud says. “The fact that I’m so vocal about my journey gives other people permission to speak up too. The whole point of my podcast was to make it inspirational and show lawyers that you don’t have to feel stuck. I feel lucky every day to reach people.”

Many of these young attorneys are also redefining how and when they work. “We take meetings all over the city, we meet at each other’s houses, and we meet over brunch,” says Morris-Andrews of Chicago. “We’re not chained to the office”—even though they have an impressive one in the Willis (formerly Sears) Tower, and they work around the clock.

Rikleen believes this flexibility is a positive that leads to more sustained and focused work, not less. Older lawyers, she says, need to come around to the new way of working.

“I hear a lot of grumbling from my contemporaries. The quote would be: ‘Oh, the younger generation won’t put in the hours that we put in; they want to go away on the weekends,’ ” she says. “I don’t think that’s true. Yes, there is a desire to lead a whole life, but that doesn’t translate into a lack of commitment. It’s just in a technologically driven world, millennials understand there are a lot of ways they can accomplish what needs to be done.”

In the end, millennials’ confidence, tech savvy and willingness to establish new work patterns will play an important role in establishing the future of law. As boomers retire in large numbers, there won’t be enough Generation Xers to take their place.

As a result, Rikleen says, millennials’ increasing role offers an “unprecedented chance to reconsider how and where we work.”

This is crucial as millennial strengths are increasingly becoming client preferences, Blank says. “So it behooves an organization—a law firm—to think about what millennials do, what drives them and what their preferences are. Because the reality is that that’s what more and more of their clients want.” n

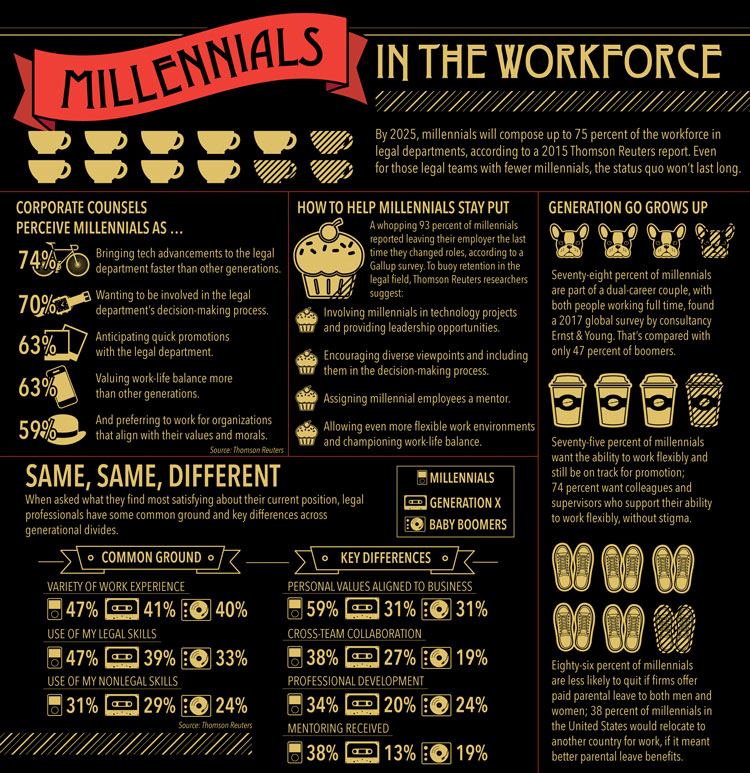

Infographic by Sara Wadford

This article was published in the January 2018 issue of the

Kate Rockwood is a freelance writer living in Chicago. She was born at the tail end of the Gen X generation.