May 20, 1863: The 10th Supreme Court Justice

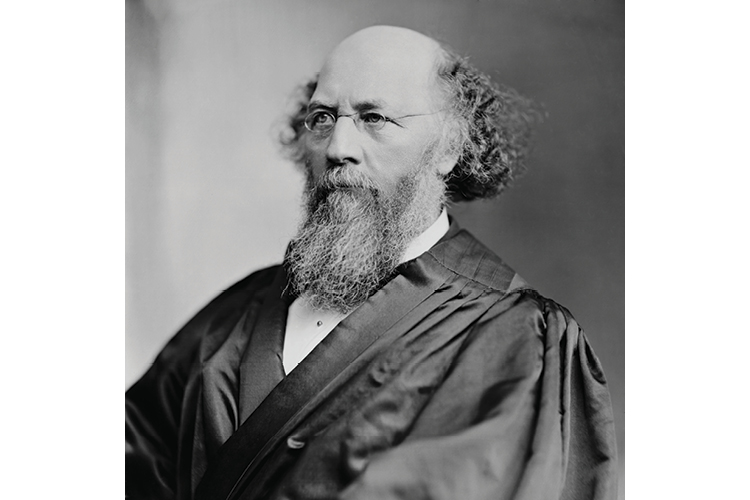

Stephen Johnson Field was nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court as its 10th justice by President Abraham Lincoln. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

By the time he was sworn in on May 20, 1863, after having been nominated by President Abraham Lincoln to a 10th seat on the U.S. Supreme Court two months earlier, 46-year-old Stephen Johnson Field presented a curious choice. Not only was he a Democrat who would need confirmation by a Republican-controlled Senate, but he also was a briefly disbarred jurist known as much for his hot-headed temperament as for his keen legal mind.

Born in Connecticut, the son of a Congregationalist minister, he was educated at Williams College and subsequently practiced law in New York City with his older brother. But his judicial resumé was built not in the refined salons of East Coast politics but in the rough-and-tumble of the California Gold Rush.

In January 1850, not two years after California was wrested from Mexico, Field arrived in what became Marysville, a boomtown near Coloma, where the Gold Rush began. Still operating under a rough-hewn version of Mexican law, Marysville was organizing itself, and just three days after his arrival, Field was elected alcalde, a kind of hybrid mayor/justice of the peace.

Without the benefit of jails or formal judicial institutions, the 33-year-old Field decided cases informally, pulled jurors off the streets and ordered the public whipping of thieves. He also made enemies, enough that he fashioned a sackcloth coat to conceal two loaded pistols in its pockets; and enough that he was party to at least three unconsummated duels.

Field was elected to California’s first legislature, where he helped create the state’s court system. But he was defeated for a second term, an outcome he blamed on political chicanery. In 1857, after establishing a lucrative private practice, he won a seat on the state supreme court. Two years later, Field replaced California Chief Justice David Terry when Terry resigned to pursue a duel with a state senator—whom he subsequently killed.

In 1863, Congress created a 10th federal judicial circuit to accommodate growth in the West. Since U.S. Supreme Court justices were required to “ride circuit” in each judicial region, the court was expanded from nine justices to 10. And Field, a steadfast unionist in the highest court of the nation’s westernmost state, was a rife political choice for the newly created seat.

Field served until his resignation in 1897, but his contentious reputation never deserted him. In 1888, Field presided over a case involving Terry. The prior chief justice was representing his wife, the former Sarah Althea Hill, who for years had pursued a divorce settlement from silver tycoon William Sharon for a marriage he said never existed. During raucous proceedings, Terry and his wife repeatedly threatened witnesses, lawyers and Field himself, who not only ruled against them, but also jailed both for contempt. A year later, Terry was shot dead by a federal marshal, David Neagle, after he physically attacked Field in a train depot.

Neagle was arrested and charged with murder by the county sheriff on grounds that he had no specific authority to protect Field. The justice recused himself in the resulting habeas case, In Re: Neagle, in which the Supreme Court ruled Neagle had acted within his official duties and that the shooting was justified.

Field served as the court’s only 10th justice until May 1865, when the death of Justice John Catron reduced the court to nine. Although Congress putatively reduced the size of the court to seven justices after Lincoln’s assassination, it reestablished the nine-seat court with the Judiciary Act of 1869.