Letters: Weighing in on War Powers

WEIGHING IN ON WAR POWERS

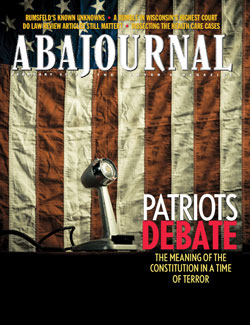

In “Patriots Debate,” February, about the power to “declare war,” professors John Yoo and Louis Fisher certainly examined the historical, practical and political issues thoroughly.

May I suggest that what is left of the congressional power to declare war is this: Unless a majority of each house of Congress declares specifically that the USA is “at war,” there can be no curtailment of domestic civil liberties. I acknowledge the need to curtail certain liberties in war time, as during World War II, but I think the curtailment was justified only because Congress authorized the status of war. To allow a president, on his own, to declare that a war is in progress and then use that declaration to justify curtailment would be intolerable.

Ann M. Lousin

Chicago

I cannot believe a respected trade journal would include Yoo in a debate about the war powers granted by the Constitution. You would be hard put to find a more discredited source, co-architect of the blatantly illegal torture and surveillance policies of George W. Bush’s criminal regime. While opting not to prosecute him, an internal Justice Department inquiry nonetheless sharply rebuked Yoo and his Office of Legal Counsel colleagues for gross abuses of their positions.

Yoo still faces a civil lawsuit in the Northern District of California filed by torture victim Jose Padilla, alleging Yoo egregiously abused his position. The complaint has survived a motion to dismiss.

I assume you invited Yoo because noted legal scholar Dick Cheney declined. Shame on you.

Mark Brodin

Newton, Mass.

I always find it remarkable how the proponents of expanded executive power, such as Yoo, are able to convert Alexander Hamilton’s praise of “energy in the executive” as sufficient basis to ignore the plain language of the Constitution itself granting to Congress the power to declare war.

It is utterly absurd to propose that the framers intended that “declare war” meant something entirely different than “make war,” and left entirely to the executive the affirmative power to start a war (other than a defensive war). As a side matter, it is usually those who promote the most extreme expansion of executive power in the context of war-making who argue most passionately that the Constitution must be “strictly” construed based on its language as used at the time of its adoption.

Apart from this citation to Hamilton, I have never seen anything that suggests the framers intended a narrow interpretation of “declare war” intended to be substantively different from “to make war.”

David B. Simpson

Tenafly, N.J.

I fundamentally disagree with Yoo, and this quote of his is at the heart of why he is so dangerous: “Time for congressional deliberation, which leads only to passivity and isolation and not smarter decisions, will come at the price of speed and secrecy.”

In other words, staying out of a conflict is bad (not smart). And killing in secret is somehow good.

Michael P. Jensen

The Woodlands, Texas

… AND ON LAW REVIEWS’ POWERS

“The High Bench vs. the Ivory Tower,” February, about the uselessness of law review articles, failed to mention one delicious irony: In 1960, no one interpreted the Second Amendment to guarantee an individual right to own firearms. Then a law review article was published taking that position. Then another, citing the first one. The process was underwritten, in large part, by the National Rifle Association. After five decades of law review articles all citing each other, this previously ridiculous proposition is now enshrined as constitutional law, thanks to decisions made by the U.S. Supreme Court headed by none other than John Roberts.

I guess “abstract and irrelevant” is in the eye of the beholder.

Andrew D. Thomas

Evansville, Ind.

MARRIAGE AND HISTORY

“A True Love Story,” February, discusses Nancy Buirski’s documentary film The Loving Story, which chronicles Loving v. Virginia, the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down Virginia’s statute prohibiting interracial marriage.

The article states: “Buirski … says the documentary has unusual relevance today with the debate over marriage equality.” She makes the common mistake of equating elimination of proscriptions against interracial marriage with changing the definition of marriage to include same-sex partners. These concepts are not, in fact, similar.

Under the common law, there was never any proscription against interracial marriage. Consequently, in Loving, the Supreme Court was not changing the historically recognized concept of marriage in any way, but instead simply restoring marriage to what it always had been under the common law—the union of one man and one woman without any racial restrictions. Advocates of same-sex “marriage” seek to change the historically recognized concept of marriage so as to encompass relationships that have never before been recognized as being within the bounds of marriage. Apples and oranges.

Bradley S. Abramson

Scottsdale, Ariz.

‘MIDNIGHT APPOINTMENT’ MIXUP

I started reading John Gibeaut’s “Co-equal Opportunity,” January, and was struck by what I believe is a significant misstatement on the first page. He writes that “the lame-duck Federalist Congress and outgoing President John Adams raised opponents’ ire with bills that allowed Adams to appoint dozens of their party faithful to judgeships, including Chief Justice John Marshall.”

Marshall was indeed appointed near the end of Adams’ term, after the 1800 election. However, his appointment was made possible by the resignation of Oliver Ellsworth on Sept. 30, due to poor health. No congressional bill was involved. He was not one of the so-called midnight appointments made possible by passage of the Judiciary Act of 1801, and to whom Gibeaut was really referring.

Stephen L. Sepinuck

Spokane, Wash.

ANOTHER TAKE ON DNA TESTING

“An Arresting Development,” January, misses the mark on several points. DNA was dragged into court rooms by prosecutors, often over the fevered objections of defense lawyers, and has turned into a magic bullet that most often proves guilt and in rare but spectacular cases has exonerated the wrongly accused. As DNA testing has become more common, it is increasingly likely that a person who did not commit an offense be cleared before formal charges are filed or before trial. But many of the same civil liberties lawyers who call for greater use of DNA apparently want to prevent the very samples that could exonerate (or convict) from being gathered.

Most disturbing was the graphic of a police officer hoisting an outsize syringe. No mention is made that most DNA samples are now taken by using a Q-tip-like swab from the mouth of the subject—something that is in fact less invasive than fingerprints.

The article fails to mention that the markers used for DNA identification are considered “junk DNA” for the purposes of genetic testing, which makes largely irrelevant claims that the government will be able to test a drunk driver’s likelihood of developing Tay-Sachs disease and presumably illegally selling it to an insurance company.

Joshua Marquis

Astoria, Ore.