Letters: Rebel-Rousers

Rebel-Rousers

What I liked about this year’s crop of Legal Rebels (September): Two were not lawyers. Too often we forget how important paralegals and other nonlawyer legal workers are. Glad to see some get some recognition.

What I didn’t like: Not one of them was doing anything remotely close to public interest law. And none were fighting back against the corporate takeover of our society. In dark days like we are in now, we need some real rebels, not just corporate shills who are inventing new ways to make more money making rich people richer. Why not feature a lawyer or two working on poverty issues or some of the lawyers fighting against the likely unconstitutional state immigration laws?

James M. Branum

Oklahoma City

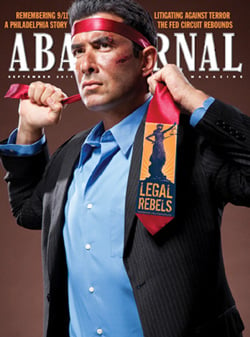

Your Legal Rebel campaign has gone too far. No lawyer should be glorified for going Rambo with a tie, or any other accessory, on his or her head. Does the guy on the cover have a brief in his pocket or some kind of weapon?

Worse, the practitioners you highlight would, apparently, never reach the white-knuckled and blood-secreting state of anger or desperation that you portray on the cover. The lawyers you profile clearly respect our profession, its decorum and its rules of professional responsibility. Why trivialize their achievements with such an insulting cover?

Worse, as I am sure you are aware, our profession has a very high rate of suicide and depression. Lawyers are not immune to our economic downturn. Does this cover pour salt in the wounds of struggling lawyers across America? Please clean up our image.

Noah M. Hoagland

Salt Lake City

I find it hard to applaud the efforts of David Perla, who outsourced legal research responsibilities to India, or Francis Burch’s effort to create an even bigger megafirm.

While I appreciate the need of all people for a living wage and clean environment in which to do business, the need for jobs in America is at an all-time high. Entrepreneurship and the private sector are being touted as the best way to turn the economy around. What may be more uncertain is how democracy ultimately will fare when yoked to capitalistic activities.

Helen Nowlin

Vancouver, Wash.

INSIDER INFO ON PHILLY CASE

The provocative point of “Reliving the Philadelphia Story” September, was that by upholding the prisoner release order in Brown v. Plata in disregard of the crime wave that engulfed Philadelphia two decades ago as a result of a similar federal prisoner release order, the U.S. Supreme Court has exposed Californians to the risk of a similar calamity. As the lawyer who negotiated and enforced the consent decrees on behalf of the inmate class in Harris v. City of Philadelphia more than two decades ago, I have a different perspective.

By my reckoning, the Brown majority served the republic well by refusing to gut the Eighth Amendment on the strength of alarming tales of crime spawned by the Harris decrees. They did not “force the city to release thousands of inmates” as your article has it, and Philadelphia did not experience a crime wave in 1993-94. And attributing the killing or wounding of six police officers to the decrees is as groundless and garishly irresponsible today as it was when the charge was first uttered.

According to the police department, Philadelphia was and remained the safest of the nation’s 10 largest cities throughout much if not all of the period spanned by the Harris population control mechanisms. After the district court dismantled the controls in November 1995, the rate of violent crime reported by police rose to levels never seen under Harris—as did, of course, the jail population. The decrees achieved a moderate degree of population control by disallowing admission into the city’s overcrowded jails of defendants charged solely with nonviolent crimes, including nonmajor drug offenses. Harris did not compel nor bring about the release of a single inmate serving time on a conviction. To an overwhelming extent, the defendants “released” from incarceration were those awaiting trial who would have been freed on their own recognizance or on bail at their preliminary arraignment under the system existing both before and after Harris.

Doubtlessly, crimes were committed by people awaiting trial under the Harris regime just as occurs under any system that does not detain all defendants. But a rearrest is not tantamount to a finding of guilt, and the 1993-94 rearrest statistics you quoted are silent as to the percentage of rearrested defendants who were convicted on their new charges. The distinction is important in a system like Philadelphia’s in the 1990s in which overcharging was rampant and the conviction rate well below 100 percent. That consideration aside, was the rearrest rate among the pretrial population any higher under Harris than it was before or after it? Without that comparison, the public safety indictment of the Harris decrees loses all validity.

Writing for the majority in Brown, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy did me the honor and history the favor of footnoting my 1995 written submission to the Senate Judiciary Committee that pointed out the lack of documentation for the Philadelphia district attorney’s inflammatory attribution of murders and other crimes to the Harris consent decrees. To be clear, although participating in the Harris litigation, the DA never attempted to prove in any judicial proceeding any of the “facts” published in your article and before that in the prosecutors’ Brown amicus brief and in repeated submissions to federal lawmakers.

Bad, i.e., inaccurate and misleading, facts make bad history, which is then handy for making bad law. Congress never sought verification of the district attorney’s statistics and emotion-laden anecdotes before citing them as justification for curtailing federal judicial power to remedy inhumane prison conditions through the Prison Litigation Reform Act of 1996. It is too late to prevent passage of the PLRA, but it is not too late to correct the historical record.

David Richman

Philadelphia

OBJECTION DIRECTIONS

I enjoyed Jim McElhaney’s article on the proper way to make objections, “Play by the Rules,” September. I agree with the notion that specificity is key to proper objections. However, I do recall a time when my frustration with opposing counsel’s repeatedly asking improper questions led me to offer a “generic” objection—and the court’s frustration with the questioning led to sustaining it. This is the exact colloquy:

Question: And isn’t it a fact that in that report that was requested it was almost accidental that one of your men, Mr. Trettle, had gone to a conference in New York and while there he related this and gave them the few papers that he had, and they were returning those papers?

Mr. Hunt: Objection for every possible reason I could think of, your honor.

The court: Objection sustained.

Counsel for a co-defendant in this case had this colloquy framed and gave it to me.

Gary Hunt

Pittsburgh