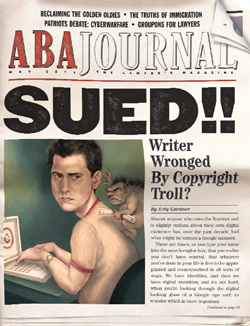

Letters: Copyright Conundrums

COPYRIGHT CONUNDRUMS

Regarding “The Righthaven Experiment,” May: A focus on actual harm and damages and how we actually create and consume content today would be worthwhile. Perhaps we need to re-examine a basic premise of copyright law—strict liability.

Should the autistic blogger who republishes a photograph deliberately posted on the Internet for public consumption really ever be sued, regardless of any fair use defense that may be available? Perhaps a copyright small claims court would be of assistance to provide a cheaper alternative to federal litigation when the harm is real.

The reality is that all litigation in the U.S. is expensive and time-consuming. If there are insufficient damages, there are always practical constraints to commencing a lawsuit (regardless of the nature of the claim), unless of course money is no object (which is rarely the case). As to the notion that there are not good copyright lawyers available nationally, that is just nonsense.

Carol Maue

Rochester, N.Y.

Good article. I think we need to sit down and have a hard discussion about copyright in this country. I was against the Stop Online Piracy Act and the recent attempts to crack down, and said so publicly. That does not mean that I think copyright should die.

I have represented a number of people accused of copyright infringement in BitTorrent cases. Usually it is a pornographer who makes a cheap movie, watches to see it gets downloaded by a few hundred people, and then he employs one of a handful of firms that go after the downloaders en masse. They typically want $3K to settle the case, using shame as a primary tool.

Some of these guys work with a website that efficiently settles the cases for $200 each, which is the statutory minimum for deliberate infringers. This minimal amount is fairly reasonable, I think.

If we set the law so that the $200 minimum is the legally preferred norm, rather than the $3K, we could get back to a reasonable balance between protection and legal extortion.

In the BitTorrent cases, the plaintiff asks the court for a subpoena to gather the names and contact information from a hapless ISP. Then the ISP sends a notice to the alleged infringers. All the notices that I have seen include a link to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which has a whole list of copyright defense attorneys.

Warren Norred

Arlington, Texas

Copyright trolls should be left out at night, so they can turn into the rocks in the morning.

To be serious, I don’t see any problem with copying. I am an author of a few popular books on various topics (not related to law)—pet care, cooking and so on. I saw pirate versions of my books quite often on various websites. Every time a new one was released, I’d go to a local bookstore to take a look. In a couple days, they would be sold out—despite there being a free pirate version. So much for copying.

I believe SOPA and the Protect IP Act were written by seriously mentally ill people whom nobody helped while there still was a chance.

Anna Gray

Alexandria, Va.

Patent, trademark and copyright litigation is not for the meek. The rights given by our various federal statutes do not guard against infringement but merely give the tools to go forward through the courts to protect the intellectual property. The real challenge is in enforcing those rights.

Clients are blissfully unaware of the cost of protection. Many cases are either abandoned in the early stages or never initiated. Mass litigation as described in this article is usually counterproductive. Good facts, and good cases, make good lawyers. Bad facts and bad cases make for bad outcomes.

Brice Recker

Columbus, Ohio

Eriq Gardner’s article highlights a fundamental flaw in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, namely its extensive ISP “safe harbor.” At the time of drafting the DMCA, some of us envisioned an easily usable system of micro-licensing that could be administered by the telecommunications companies and other access providers that were offering dial-up services and later broadband access. However, they did not want to be bothered at the time, and still don’t.

Now, as their traditional business models provide smaller profit margins, they are seeking ways to profit directly from content. Examples are Verizon’s FIOS and Comcast’s Xfinity services. Had these companies and the now nearly defunct AOL been more interested in cooperating in the development of easily usable, fairly priced, consumer-friendly licensing models at the outset of the Internet era, everyone would be better off today. However, it is probably too late for that.

An alternative that might still be possible and that would be much more helpful to content providers than a copyright small claims court would be some kind of statutory license, such as that in Section 111 of the Copyright Act, that addresses the problem of retransmission of cable television signals and generates more than a half-billion dollars a year for content owners.

Such a statutory license could cover ISPs—not only traditional telecoms and cable companies but also hybrid Internet service providers such as Google and YouTube. Clearly these companies generate sufficient revenue and profits to enable them to share some with the creators of copyrighted works while relieving both creators and users of content critical to their business of the unbearable burden and complexity of infringement litigation of the kind described in this article.

Bruce Lehman

Washington, D.C.

The Righthaven episode demonstrates the same issue of perversion of a legal framework that patent trolls exploit with patents and the financial markets have done with derivatives.

In all three cases, legal vehicles (copyrights, patents and derivatives) that provide fundamental protections for originators of value are commoditized and utilized as vehicles for speculation, providing neither the original benefits to society that the copyrights, patents and derivatives did to the facets of society for which they were originally created, nor the stability to society that was the other purpose of the creation of copyrights, patents and derivatives. In the case of patents, the situation is exacerbated by the plethora of patents granted that fail to meet even the minimum standards required by patent law.

This has gotten so ridiculous that there’s even a patent application (No. 20080270152 by Halliburton), titled “Patent Acquisition and Assertion by a (Non-Inventor) First Party Against a Second Party,” that attempts to patent the business model of patent trolling. If the past incompetence of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is any guide, it will be granted.

Tyrone Jackson

Boston

Attempting to turn this into a political position issue is incorrect. Many of those that Righthaven sued (including me) are actually on the right end of the spectrum. The core problem is that the actual damages that the Las Vegas Review-Journal suffered from the one article that my co-blogger copied too much from probably amounted to a few pennies, if even that. Indeed, it is possible that additional traffic they received because of our links might have actually made them a beneficiary of what we did. News stories are not in the same category as music or video in terms of economic damages. Not even close.

The second problem is that a polite (or even rude) request to reduce the amount copied would have, in nearly all cases, resulted in immediate compliance. Copyright violations (as opposed to fair use) are almost always inadvertent. Even a request for a modest payment (say $250) as compensation would likely have been paid without needing lawyers. Steven Gibson’s delusion that there were quadrillions of dollars in revenue available for him to grab onto was the big error here.

Clayton E. Cramer

Horseshoe Bend, Idaho

Perhaps we should recognize that most content is not worth much and that broad dissemination is worthwhile. Perhaps we should recognize that the difficulty of suing for most infringements is a good thing in order to provide breathing space and for distribution of content of limited value. Perhaps we should recognize that for significant instances of infringement, equitable remedies like injunctions and exclusions and takedowns are the way to go.

The question is really about payment to authors or copyright holders, not about rights per se. Rights are a means to encourage the creation and dissemination of works. How many times must an author be paid for a news article? Photograph? Story? Most authors are paid employees anyway and don’t get royalties. Who sued for people making Xerox copies? Who knew it was happening? Now we know because we can track it.

This is sound and fury signifying very little for nearly all works.

There are real problems in the copyright system. But the cost of litigation to enforce rights is way, way, way down the list. The broad derivative-works right is one of the major problems. The seeking of ever more aggressive ways to tie up not only copyright expression but ideas is another. The collateral damage from overly aggressive assertion of rights is another. The exclusion and ripping off of works of creators by big companies is another—the artists/authors don’t get paid; the companies make the money.

Steve Jamar

Washington, D.C.

RAINMAKING VS. DIGNITY

Regarding “Coupon, You’re On,” May: I’m all in favor of thinking outside the box, but I must ask: What’s next? Attorneys standing on street corners at busy intersections holding signs that say “Half-price—Going out of business sale”? Do we have to become like furniture stores and game shows?

The questions do not stop with whether it is ethical; they end with the question “Should we?” I think not. There are innumerable ways to market oneself with a degree of dignity that reflects how we practice as a profession, and most attorneys know (or can learn) these ways whether they are with big law firms or solo practitioners. If one cannot get business by marketing oneself or one’s law firm in a dignified manner reflecting that we are professionals, maybe one should go into another line of work.

If you were sick, would you really go see a doctor because the doc offered a “deal of the day” or a “half-price coupon”? I would not.

Barry V. Frederick

Hoover, Ala.

I have not looked at the rules for a long time but thought that discounts were not permitted because there is no clear indication what the list price was.

We price out work on a flat-fee basis, but that is after an evaluation of what the work is worth. I personally would not want to waste a day explaining to the grievance committee how I arrived at the fee to which I applied a Groupon discount.

Again, ladies and gentlemen, we are attorneys and as members of the bar occupy an office of trust and responsibility. Let us comport ourselves with the dignity that the office requires.

David G. Parent

Wallingford, Conn.