Legal community meets relief challenges after hurricanes Harvey and Irma

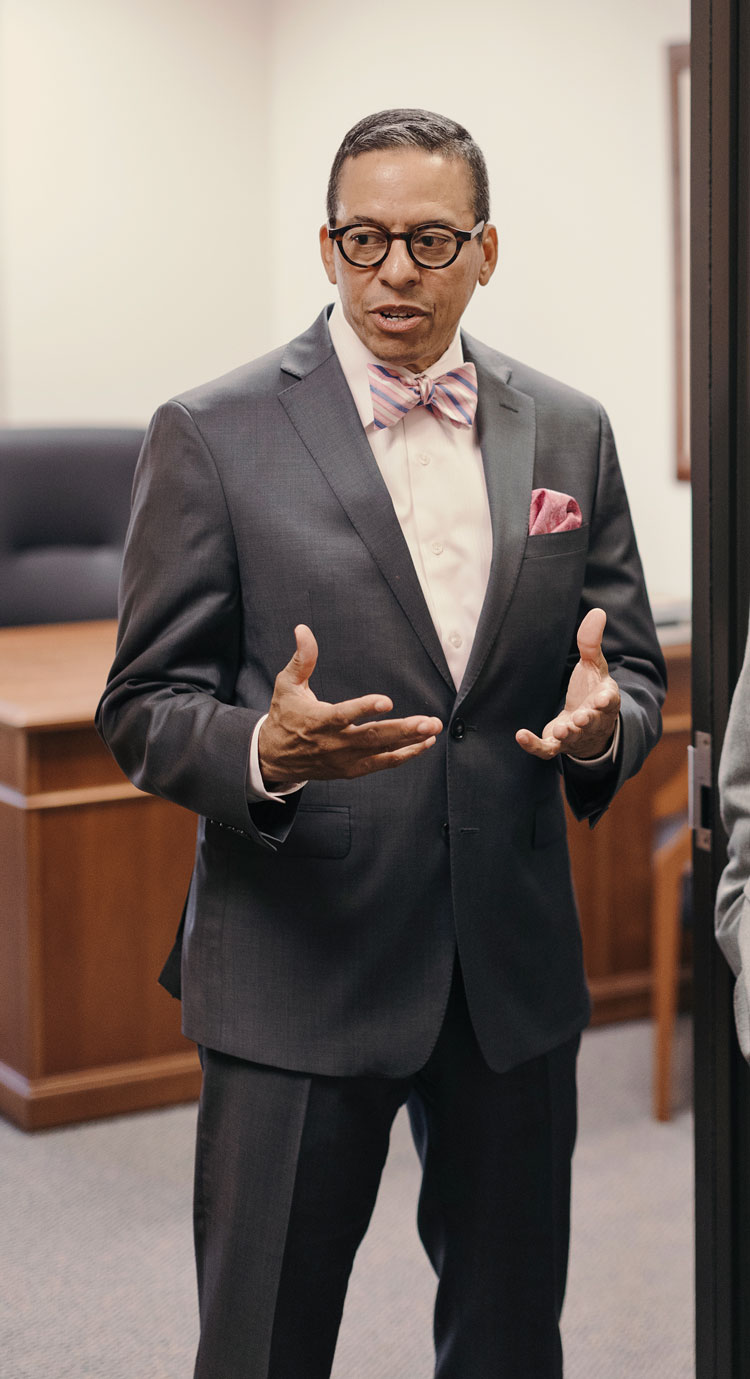

Judge Marc Carter. Photo by Todd Spoth.

Judges say defense attorneys have been understanding about the situation. Tucker Graves, president of the Harris County Criminal Lawyers Association, said in the months after the storm he’s heard complaints from some lawyers about the slow speed of trials. But Graves credits judges for recognizing the problem by setting the oldest jail cases for trial first.

Carter and Wallace have a lot of time to compare notes because they’re sharing a courtroom. When the Criminal Justice Center was destroyed, judicial authorities moved all 36 criminal judges into courtrooms designed for their civil colleagues, sitting two to a courtroom. To make room, the civil judges also doubled up. Wallace and Carter ended up sharing a courtroom at the Civil Justice Center.

Sharing a bench isn’t that much of a hassle, but being in a civil courthouse has been a major problem for criminal cases. The civil courthouse has no direct physical connection to the county jail and no cells for holding in-custody defendants. Thus, it initially was used only for hearings involving defendants out on bond.

For jailed defendants, hearings were being conducted in a makeshift courtroom at the jail—actually a series of long folding tables in a large open room. It’s loud, and privileged attorney-client conversations are conducted within everyone’s earshot. And because the public is not admitted inside, families must watch via closed-circuit television at the civil courthouse. Judges presiding over these hearings take turns visiting the jails.

People are doing their best, the judges say—but all the same, they’re concerned about how this will play out in the long run. They’d like to move back into the Criminal Justice Center as soon as they can, even if that means walking around construction.

“Yeah, we’re going to be inconvenienced,” Carter says with a laugh, “but … we would prefer to be inconvenienced in our old building because it would just serve the criminal justice system and the citizens of Harris County better.”

THE AFTERMATH: Proof of Hurricane Harvey is everywhere. Photo by Todd Spoth.

For public defender Robert Lockwood of Florida’s 16th Judicial District, the problem was not a lack of courthouses—it was getting there. His district encompasses the Florida Keys, a series of islands south of Miami, strung like beads along 110 miles of U.S. Route 1. It’s the only way to drive through the Keys, and after Hurricane Irma, it was lined with downed trees, washing machines and other detritus thrown around by winds as high as 130 mph. There was also a shortage of fuel—and Lockwood had sheltered in a hotel ballroom in Key West, 50 miles from where a makeshift court had been set up in Marathon. He had to call on favors to get the necessary gasoline.

Though new arrests were minimal after the storm, he says, a bigger problem was the inmates already in jail, who had all been evacuated to Palm Beach County. That’s a five-hour drive away, and the evacuation dragged on for two weeks. Although the Florida Supreme Court had suspended legal deadlines for the hurricane, Lockwood didn’t like holding people for so long without charges—or in some cases, past their release dates.

So Lockwood convinced the high court to authorize his district to hear cases in Palm Beach County, and he enlisted the local public defender’s office to help his staff connect the Keys inmates with their families on the outside. It wasn’t necessary; jail authorities moved the inmates back shortly after everything was ready. But the cross-circuit cooperation broke new ground in which lawyers committed to helping one another for the clients and their families. “That’s why we all tried to get together,” Lockwood says.

James McDonald. Photo by Todd Spoth.

LEGAL AID IN ACTION

Texas resident James McDonald has been eligible for disability benefits since 1995—for PTSD and depression stemming from Navy service in the Middle East and Somalia—but he never made the claim. He didn’t want to think of himself as disabled. But his emotional equilibrium suffered after Hurricane Harvey, when his landlords started demanding that his family vacate their house in the Houston suburb of Baytown.

There was little money to make the move; McDonald’s hours at his catering job had dropped to nearly zero following the storm, and his girlfriend hadn’t worked at all for a few weeks. Nevertheless, the landlords threatened to throw their things into the street if they didn’t leave within five days. Then they started a campaign of harassment, banging on the doors and sending a barrage of text messages. McDonald’s daughter, a senior in high school, was too anxious to sleep. And McDonald, who was driving for Uber at night to make ends meet, was finding the situation difficult himself.

McDonald got connected to the veterans unit at Lone Star Legal Aid. Attorney Justin Wilson got McDonald a temporary restraining order preventing the eviction and then brought him downstairs to Combined Arms, a Houston veterans’ organization that had donated office space to Lone Star. Combined Arms connected McDonald to federal disability benefits and treatment, then put him in touch with Main Street Ministries. The Christian nonprofit not only found him a new place to live but also funded the move.

He was grateful and humbled. “I’ve never accepted help in anything,” McDonald says. “And suddenly I put it out there, and not only do I find help, but it’s like they’re just falling over themselves to try to help me even more.”

Disaster Response Resources

ABA Resources

• ABA Committee on Disaster Response and Preparedness

Volunteering Opportunities

Florida attorneys can visit the Florida Bar Foundation to find post-storm volunteer opportunities for legal aid and pro bono attorneys, or visit Florida Pro Bono Matters.

North Carolina attorneys can find info on volunteering on the North Carolina Bar's Hurricane Florence page.

South Carolina attorneys can volunteer for the South Carolina Bar's disaster relief legal service hotline by filling out this form.

Not licensed in those states but looking to donate your time or money? Check out ambar.org/DisasterRelief.

ABA Journal Coverage

Hurricane Heroes: From the February 2018 issue

Legal community meets relief challenges after hurricanes Harvey and Irma

ABA mobilizes aid to Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

Lessons from Katrina

Social media unites lawyers to help those in need

For our latest natural disaster coverage, click here.

Disaster Helplines

The Disaster Distress Helpline (DDH) is a national hotline dedicated to providing year-round disaster crisis counseling. This toll-free, multilingual, crisis support service is available 24/7 via telephone (1-800-985-5990) and SMS (text 'TalkWithUs' to 66746) to residents in the U.S. and its territories who are experiencing emotional distress related to natural or man-made disasters.

For low-income individuals with disaster-related legal needs, the following phone numbers are available:

North Carolina residents: 1-833-242-3549

South Carolina residents: 1-877-797-2227 ext. 120

Virginia residents:

1-804-775-0808 in the Richmond area, or 1-800-552-7977.

Florida residents: 1-866-550-2929.

The judge who granted the restraining order suggested that the landlords wanted to make a FEMA claim, based on the misrepresentation that they lived in the house themselves. According to Brown of Lone Star’s disaster response unit, this kind of fraud is not uncommon after a disaster. In other cases, she says, landlords might use the damage as an excuse to evict low-paying tenants to make room for market-rate renters or to sell the building.

For legal aid agencies, which confront needs that far outstrip their resources, there’s no such thing as a slow day. But after hurricanes Harvey and Irma, their clients’ needs were too immediate to ignore. At first, disaster victims need help with the basics of life—securing benefits so they can eat and dealing with destroyed homes or landlord-tenant problems. Poverty exacerbates it all.

“When you’re poor, everything’s harder,” says Brown. “They’re going to recover slower and worse.”

Legal aid agencies haven’t been handling these problems alone. In Houston, another major source of legal services to low-income communities is the Houston Volunteer Lawyer program, a project of the Houston Bar Association that connects private attorneys to pro bono opportunities. After the hurricane, the program kicked into high gear to help out, starting with staffing legal services tables in hurricane shelters, along with Lone Star.

“We had over 500 attorneys sign up in the first two or three weeks,” says Michael Hofrichter, director of operations and compliance at Houston Volunteer Lawyers. “To put that in perspective, we typically have somewhere between 1,000 to 1,300 attorneys doing work for us over the course of a year.”

Photo by Todd Spoth.

Volunteers across Texas—and Florida—also showed up online and via telephone. The Disaster Legal Services program, a project of the ABA’s Young Lawyers Division, teamed up with the state bars of Florida and Texas to recruit lawyers to staff a hotline offering legal advice to hurricane victims. In all, the DLS says 932 volunteers had participated by January (and more are welcome). Both state bars also recruited their attorneys to offer online legal advice through Free Legal Answers, a project of the ABA Standing Committee on Pro Bono and Public Service that’s partially sponsored by the sections on Litigation and Business Law.

Tracy Figueroa, team manager for disaster assistance at Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, says a major source of questions is landlord-tenant problems, which tend to persist months after the storm. In the fall, her agency—which serves 68 counties along the Gulf Coast, Rio Grande Valley and Central Texas—was handling lots of those, as well as foreclosures, clearing real estate titles, problems with contractors hired to fix the damage and appealing wrongful FEMA denials.

Brown says Lone Star client Herman Smallwood had a typical FEMA appeal. He and his two sisters inherited a house from their mother years ago; he lives there and pays the property taxes, but his name wasn’t on the title when the hurricane hit. On that basis, his application for FEMA benefits was denied. As a result, Smallwood—who’s lived on disability payments since 2012—was living in a house that actually broke in places when flooding knocked it off the blocks that had elevated it. The drywall was collapsing. “The house just looked like a broken-down old horse—a brokeback horse,” he says.

This article was published in the February 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Storm Troopers: When Harvey and Irma hit the US mainland, the legal community rose to the occasion."