Legal Sleaze: Are pop culture's unethical, incompetent, crooked lawyers examples of art imitating life?

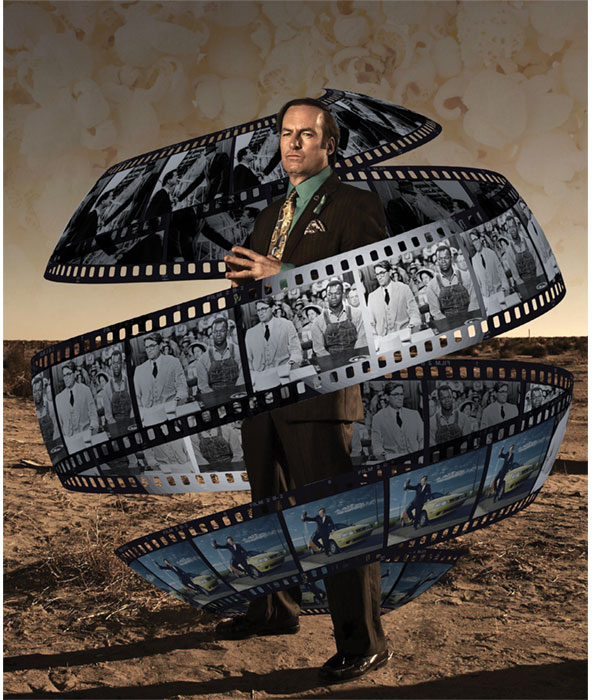

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford; photos by Mondadori via Getty Images; Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images; AMERICAN MOVIE CLASSICS (AMC) ABA

(V.O.)

Coming this fall: Justice is blind. Which is for the best, since it means she can’t see what the lawyers at Wynn, Bigg & Bragg are up to. There’s the criminal lawyer who only remembers the “criminal” part of his education. There’s the win-at-all-costs bare-knuckle brawler who considers ethics rules to be mere suggestions. There’s the incompetent ambulance chaser who runs faster than Usain Bolt whenever he hears that sweet siren. They believe that the best defense is a great offense—especially if that offense has the other team’s signals and plays and has paid off the refs. The Fixers—coming soon to a streaming platform near you. The road to justice has never been this crooked.

The above might not be for a real show, but it very well could be. When it comes to pop culture, it can be good to be bad. That’s especially true for lawyers in movies, television shows, books and plays. Pop culture is full of tropes, archetypes and caricatures that show lawyers in the worst possible light.

Not only are these characters entertaining, but they also can mean big business. Several films featuring characters who are less than competent and/or utilize underhanded or even illegal tactics have gone on to become box-office hits, most notably Liar Liar (1997), which grossed over $300 million worldwide.

Other hit films such as Presumed Innocent (1990), Legally Blonde (2001) and The Lincoln Lawyer (2011) have proved to be enduringly popular, so much so that they have been or are in the process of being remade for different forms of media. Meanwhile, TV shows such as L.A. Law, The Practice, Boston Legal, Better Call Saul and those in the Law & Order franchise not only have racked up ratings and awards but also have spawned legions of imitators. Even authors have made hay out of bad lawyers, with some, most notably John Grisham and Scott Turow—both of whom hold law degrees—writing and optioning numerous bestsellers.

Some of these bad lawyers are so popular and beloved, they end up becoming heroes. For instance, when the ABA Journal picked the “25 Greatest Fictional Lawyers (Who Are Not Atticus Finch)” in 2010, the list included characters such as shady fixer Michael Clayton (Michael Clayton), ruthless litigator Patty Hewes (Damages) and ethically challenged attorney Alan Shore (The Practice, Boston Legal).

Of course, there’s a reason why these and many other fictional bad lawyers resonate with the public: Plenty of people dislike and distrust lawyers.

In a January Gallup poll ranking professions by honesty and ethical standards, only 19% of respondents had a high or very high opinion of lawyers, putting them at a comparable level with journalists, business executives and local politicians.

Meanwhile, in a widely cited 2013 Pew Research study weighing public perceptions of the perceived contributions of 10 different industries, including the military, teaching and medicine, lawyers came in dead last.

“A good story always has to have a strong villain or antagonist,” says Michael Asimow, dean’s executive professor of law at Santa Clara University School of Law and co-author of Law and Popular Culture: A Course Book. “And as we know, the general public despises and distrusts lawyers. Representations of bad lawyers resonate with the audience because that’s what they think lawyers are really like.”

Holding out for a hero

But it wasn’t always that way. It used to be unthinkable for a studio to produce a lawyer-centric movie or television show in which the main character does anything but use his or her powers for noble purposes.

The primary paragons were Gregory Peck’s portrayal of Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and Raymond Burr’s performance as the titular character in the Perry Mason TV series (1957-1966). Both characters were heroic straight arrows revered for their greatness. Films such as Inherit the Wind (1960), 12 Angry Men (1957) and Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), and TV shows such as The Defenders (1961-1965) and Owen Marshall, Counselor at Law (1971-1974) reinforced the notion that lawyers, judges and jurors all operated in good faith.

“Up until the 1970s, about two-thirds of movies presented lawyers positively—Atticus Finch is the most famous. In many, many movies, lawyers were the good guys—competent, dedicated professionals,” Asimow says.

He argues that things started to change with the Watergate scandal, which ensnared many lawyers, including the president. And then the U.S. Supreme Court, in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona (1977), struck down bans on lawyer advertising, opening the floodgates for those commercials you see on television about getting money for you. (See “Ad it Up,” April 2017, page 34.)

“There was a change in the way lawyers were shown in the movies, and this change matches up with polling data about lawyers,” says Asimow, who co-authored the 2021 book Real to Reel: Truth and Trickery in Courtroom Movies with Paul Bergman.

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School and author of Storytelling for Lawyers, traces this change in perception back to the Vietnam War era.

“There was a deep cynicism of the law and that it didn’t apply fairly to people,” he says. “Even in movies like The Godfather and Dirty Harry, there’s this underlying notion that the law doesn’t achieve justice, and in order to get justice, you go outside the law. Lawyers are not effective in enforcing the rule of law, or worse, sometimes they’re hypocrites. They’re not achieving justice but actively subverting it.”

Meyer adds that even in movies where justice ultimately prevails, it’s often a nonlawyer who achieves it, such as Erin Brockovich, the 2000 film in which Julia Roberts portrays a legal assistant who took on an energy company.

Carrie Menkel-Meadow, distinguished and chancellor’s professor of law at the University of California at Irvine School of Law, has a more practical theory.

“I used to write about ethical issues that came from these shows, and a lot of writers were former lawyers,” Menkel-Meadow says. “I think many of these writers are people who didn’t like being lawyers, so they’re writing critiques of it.”

Dramatic license

Once lawyers are established in pop culture as sleazy, ill-intentioned or as objects of ridicule and scorn, it’s difficult to change those public perceptions. L.J. Shrum, a professor of marketing at HEC Paris, argues that most people don’t have much firsthand experience with the occupations portrayed on TV or in the movies.

“We base our knowledge on how things work based on what we see. If it seems plausible, if it seems right to you, then you accept it,” says Shrum, who studied this phenomenon in his 1995 paper Assessing the Social Influence of Television: A Social Cognition Perspective on Cultivation Effects.

Asimow, Meyer and others point to the 1982 film The Verdict as a turning point in how lawyers were portrayed on screen.

The film was based on an adapted screenplay by future Pulitzer Prize winner David Mamet and starred Paul Newman as Frank Galvin, a burned-out alcoholic who only takes on a medical malpractice case in hopes of pocketing one-third of the likely settlement and drinking it all away. But after visiting the victim, he decides to try to win the case and finds himself up against an unethical defense team willing to win at any cost and a judge who seems to be biased against him.

“Redemption stories are always interesting,” Asimow says. “That’s always a very satisfying story.”

Meanwhile, a similar phenomenon occurred on TV. Shows such as Night Court (1984-1992) and L.A. Law (1986-1994) broke with their predecessors and portrayed lawyers in a less-flattering light. In particular, L.A. Law, which was created by Steven Bochco and Terry Louise Fletcher and ran for eight seasons on NBC, was more concerned with dramatic license than a law license, and its soap-style storylines and glamorous setting made it more like Dallas or Dynasty than Perry Mason.

“Law is based on conflict. People usually go to lawyers because they have a problem or conflict with someone else that needs to be addressed,” says Marshall Goldberg, former counsel for the U.S. Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights, who went to Hollywood and wrote for shows such as Diff’rent Strokes, L.A. Law and Life Goes On. “Conflict is natural for good drama. As such, the nature of the legal profession lends itself to drama.”

Prior to joining the writing staff at L.A. Law, Goldberg wrote for the The Paper Chase, a television adaptation of the famous 1973 film about law school life that was accurate but not a hit.

On the other hand, L.A. Law was wildly successful, winning 15 Emmys, including taking outstanding drama series honors four times and landing in the Nielsen top 30 during its first six seasons. However, any resemblance to real-life lawyering was strictly coincidental.

“My perspective on legal shows, in general, is that authenticity is not really valued within the entertainment industry. It’s about ratings—what’s commercial and what’s dramatic,” says Goldberg, adding that Bochco would tell writers to focus more on the story and less on realism. “You have to get into a completely different mindset. Make it seem just authentic enough so viewers think ‘I’m entering into a fascinating world.’”

Goldberg notes that he and his father were both lawyers, and the canons of legal ethics mattered deeply to him. Yet he also knew plenty of lawyers who weren’t as ethical and provided excellent fodder for characters like Arnie Becker, the womanizing divorce lawyer played by Corbin Bernsen.

“Arnie Becker wasn’t hard to write because there are people who are like that,” says Goldberg, who is currently working on a docuseries about the criminal justice system for the Oprah Winfrey Network and Discovery+. “So much of the justice you receive depends on the quality of the lawyers involved. There’s a whole range of lawyers in terms of competence and ethical sensibilities. And that was also present on L.A. Law.”

Good vs. evil

Then again, maybe the rise of “bad lawyers” isn’t such a recent phenomenon after all. Maybe they were always there to begin with—a byproduct of the adversarial system.

As novelist Turow points out, Perry Mason may have portrayed its titular character as a hero, but that wasn’t the case for all lawyers on the show. Most notably, Mason’s usual courtroom opponent, Hamilton Burger, was certainly no hero. He wasn’t very sympathetic, nor was he very competent.

It’s not a stretch to take that to its logical extreme and portray a lawyer in much worse light—especially against the backdrop of the courtroom, which amplifies conflict and drama inherent to our legal system.

“I think the moral and ethical failings that are common to lawyers are common to all human beings,” says Turow, whose 1987 novel, Presumed Innocent, was made into a 1990 Hollywood blockbuster starring Harrison Ford. “The difference, of course, is that as lawyers, you have enormous power to do bad things. Good things as well. But the law degree and the machinery of the law often magnifies significantly the moral failings that are broadly shared: lust for power, money, the narcissism that drives the hunger to win.”

With that in mind, Turow says he uses shades of gray in his books and creates characters who have good and bad qualities. “I grew up with the Perry Mason and Atticus Finch model,” he says. “I don’t know if I believed them completely. In terms of my own writing, I really didn’t want the black-and-white world. I think I reacted against that.”

In Presumed Innocent, for instance, the main character, prosecutor Rusty Sabich, is on trial for murdering his former lover. However, he is arguably the most ethical character in the book, at least from a legal standpoint. The characters around him—from his colleagues at the district attorney’s office who are now trying to put him in prison, to the police officer who’s investigating the crime, to Sabich’s defense lawyer, to the presiding judge—are the ones doing legally questionable things throughout the course of the book. Turow says this was deliberate: He wanted to portray Sabich as someone so convinced of his own goodness that he didn’t or couldn’t see he was no better than anyone else.

“His most cockeyed moment is when he criticizes [his defense attorney, Sandy Stern] for holding up the trial judge to threaten to reveal his secrets,” Turow says. “He literally seems to be saying, ‘I really didn’t want to win that way,’—that’s a hell of a thing for a guy on trial for murder to be saying. But that reads a lot on Rusty.”

On the flip side, Fletcher Reede, the lead character in Liar Liar (played by Jim Carrey), may not have been convinced of his own goodness but was perfectly willing to lie to anyone and everyone else to convince them.

The idea for the 1997 film came to script co-writer Paul Guay one day in March 1990, when he jotted down a one-line note that read: “For one day, a guy who’s been a liar must tell the truth.” After flirting with making their lead character a politician, a used car salesman or a boxing promoter, Guay and writing partner Stephen Mazur decided to make him a lawyer—in part because they realized many people could relate to that.

“There are thousands of lawyer jokes for a reason,” Guay says.

They also felt the courtroom was an ideal setting for a clash of ideas, emotions and characters. In the movie, Reede, a compulsive liar and successful lawyer but horrible husband and father, is cursed to not tell a lie for 24 hours. The curse occurs during an important trial, so Reede must figure out how to win without being able to do what he does best.

Guay, who cites To Kill a Mockingbird and Inherit the Wind as two of his favorite movies, saw the courtroom as an ideal vehicle for Reede to realize the error of his ways.

“Our hero represents a woman who is divorcing her husband and demands child custody,” notes Guay, who says he and Mazur pitched a sequel for Liar Liar but were told Carrey didn’t do sequels. “She doesn’t care about them but wants to win. That’s a pretty emotional thing to put our hero in the middle of. But you can feel the way it changes him from someone who wouldn’t remotely think about others but is then forced to understand the harm he’s causing and become a better person.”

Like Goldberg, Guay says he and Mazur did not prioritize authenticity. “I very much want the average person to believe what it is that we’re saying, and I’m less interested in whether an expert would be able to find a minor flaw in something,” says Guay, who says he is currently working on a comedy based on a real-life story that made international headlines. “It sounds like I’m promoting lying, but I’m really promoting storytelling. Sometimes you need something that works as a metaphor or symbol or something that’s more powerful than whatever the literal facts might be.”

What’s old is new

When it comes to pop culture, themes, characters and tropes never go out of style—they just get reimagined, repackaged and remade for a new audience. In February, Apple+ announced a new limited series based on Turow’s Presumed Innocent with J.J. Abrams as a co-executive producer and David E. Kelley as showrunner. Around the same time, ABC produced a pilot for a proposed L.A. Law reboot starring original cast members Bernsen and Blair Underwood alongside several newcomers. In May, however, the network opted not to pick it up.

Nothing seems to be off-limits, as even venerated figures such as Mason and Finch have undergone a darker, grittier face-lift for a more cynical generation. In 2020, Perry Mason premiered on HBO, portraying its title character (played by Matthew Rhys) as a PTSD-scarred World War I veteran who drinks too much and makes a living in the sleazy world of private investigations prior to becoming a famed defense attorney.

And in December 2018, an Aaron Sorkin-penned adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird opened on Broadway that presented Finch as a more complex figure who seems comfortable with, or is at least indifferent to, the racism around him and only becomes the anti-racist icon we know and love at the end of the play.

The Harper Lee estate sued Scott Rudin, the producer of the Broadway adaptation, in March 2018, alleging that the play undermined the original spirit of the book and character. According to the New York Times, Tonja Carter, lawyer for the Lee estate, even said Sorkin’s Atticus was “more like an edgy sitcom dad in the 21st century than the iconic Atticus of the novel.” The lawsuit was settled two months later.

For Menkel-Meadow, bringing back characters such as Finch and making uplifting movies about lawyers like the 2019 film Just Mercy, an adaptation of the bestseller by Bryan Stevenson about his work helping death row inmates, show that some people are getting sick of all the bad lawyers.

“I think there’s a real need to have heroes again, to want to believe there are good people,” Menkel-Meadow says, pointing out that in December 2021, New York Times readers picked To Kill a Mockingbird as the best book of the last 125 years. “Good lawyers can make the world and the country better. And right now, we’re in one of those cultural moments where people want to believe in something good.”

Meyer, however, sees it as a product of our modern-day society, where divisiveness and cynicism are rife.

“When you reinvent things, like songs, the listener has the model of the old song in their mind and you play against that,” Meyer says. “I think that’s exactly what happens when someone like Aaron Sorkin reinvents Atticus Finch. He plays against the original to fit our times.”

Or maybe it just boils down to the simple fact that there are more sources of content available than ever, and that has been a boon for longer, more complex storytelling. Shrum argues that studios, desperate for content, will care more about quality than whether they’re promoting good lawyers or bad ones.

“We need more stories, and it’s a question of whether you can find a good story,” he says.