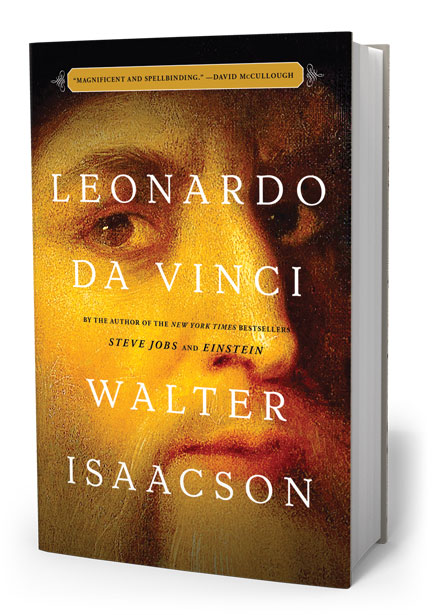

Da Vinci’s code: Lawyers can draw valuable lessons from the master in Walter Isaacson’s 'Leonardo da Vinci'

Looking at ‘lady with an ermine’

As I surf through the reproductions in the book, I stumble onto one of Leonardo’s earlier Milan portraits—“Lady with an Ermine.” This portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, mistress of the de facto Duke of Milan, is not as famous as the “Mona Lisa,” although Cecilia shares the Mona Lisa’s inscrutable smile. She is a remarkable lady, nevertheless. To me, Leonardo’s portrait of this young woman conveys and predicts the mystery, allure and beauty characteristic of modern iconic movie stars (e.g., Audrey Hepburn). Leonardo’s composition also purposely suggests the motion of Cecilia’s thoughts; animating a complex narrative in which the viewer becomes complicit and an active participant. It is, for me, a theatrical or cinematic storyline: I follow Cecilia’s dramatic attention, intentionally directed offstage. Who is she looking at? A lover, perhaps? She strokes the pet ermine in her lap with sensually elongated fingers. Her profoundly intelligent eyes mirror her attention—and so do the ermine’s!

There is precision in the lighting, in the theatrical posing and posture of Cecilia’s body, in the meticulous attention to details of her costume; and in her expression and her focus and her physicality all emphasized by the dramatic staging. Leonardo’s Cecilia becomes truly a life force; a modern character—alluring and unrepentant and ironic, too.

Her picture tells a story that intimates her thoughts and simultaneously reveals the complexity of her character. Leonardo’s painting suggests a frame in the movement of a complex visual and cinematic story. More than anything else, Leonardo is a visual storyteller whose images inevitably point to something beyond themselves, conveying meanings that move viewers emotionally in ways that could not possibly be anticipated. I wonder whether lawyers can attempt similar work with images, just as they often try to do with words.

Lessons from Leonardo

In his last chapter, Isaacson’s exploration of Leonardo’s biography and art and science becomes, curiously, a self-help book of sorts. Isaacson formulates a list of lessons of what the artist teaches us today, including: Be curious, relentlessly curious. Think visually. Retain a childlike sense of wonder. Observe. Start with the details. See things unseen. Respect facts. Indulge fantasy. Take notes on paper. It is as if he is attempting to make his open-ended exploration of Leonardo’s genius specifically relevant for his general readers, to provide a list of convenient “takeaways.”

So what are my storytelling lessons for lawyers? Trust your perceptions and intuitions, just as Leonardo did. Always keep your storyline in mind and employ analytical skills and artistic talents in service of it, just like Leonardo. Supplement intuitive perceptions with meticulous investigation and research, and be ready to give up upon ideas that are not working. Fit your observations into narrative frames without manipulation or distortion. Think like an artist; creativity and inspiration are important in legal storytelling as in Leonardo’s paintings, and so is revision and endless modification. Learn how to read and interpret surfaces and images, and trust your assessments of “character.” And understand how images strategically convey unfolding stories that ineffably pull an audience toward meanings that are often more powerful than words.

Warm reflections

The book remains open in my lap. My lessons are trivial compared to the genius and majesty of Leonardo’s paintings and work, and the eloquence of his own codex reflections and observations. I urge lawyers interested in the now-crucial subject of visual storytelling to read Isaacson’s book, relish Leonardo’s art and share his principles of visual storytelling practice embodied in his art and science. Some new appreciation of Leonardo’s genius may rub off on you, as it did for me. Also, enjoy Isaacson’s rendering of Leonardo’s remarkable biography; Leonardo as an outsider, an illegitimate son who trusted his creativity and genius and led a fearless life of professional collaborations and personal engagement with the events and characters of his time. The fullness of his life informed his art and contributed to his scientific and aesthetic discoveries, too.

I recall that August day as the sun set and it was too dark to read. I packed my folding beach chair and returned to the car. My cellphone was vibrating. After sharing the afternoon with Isaacson’s Leonardo, I returned to the world of screens and surfaces and shards of endless spinning images. We still have much to learn from Leonardo.

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of