Is this a moment or a movement? 6 civil rights lawyers reflect on recent demands for racial justice

Attorney John Burris stands before a mural in Oakland, California, commemorating George Floyd.Photo by Tony Avelar/ABA Journal .

Lawyers have a long tradition of supporting efforts to bring racial and social justice to this country. They’ve argued important civil rights cases, demanded police accountability and advocated for public policies to address systemic and institutional racism. Recent killings of unarmed Black people by police have sparked a new wave of protests and demonstrations on a scale not seen in decades. Once again, the nation has been forced to pay attention. Public support of Black Lives Matter has surged, and one poll found that 67% of Americans believe racial discrimination is a big problem in the U.S., up 16 percentage points from five years ago. Does the increased support suggest meaningful change is coming? The ABA Journal interviewed six lawyers who have worked on the front lines of civil rights and social justice to get perspective on what has changed since the 1960s and what the future may hold.

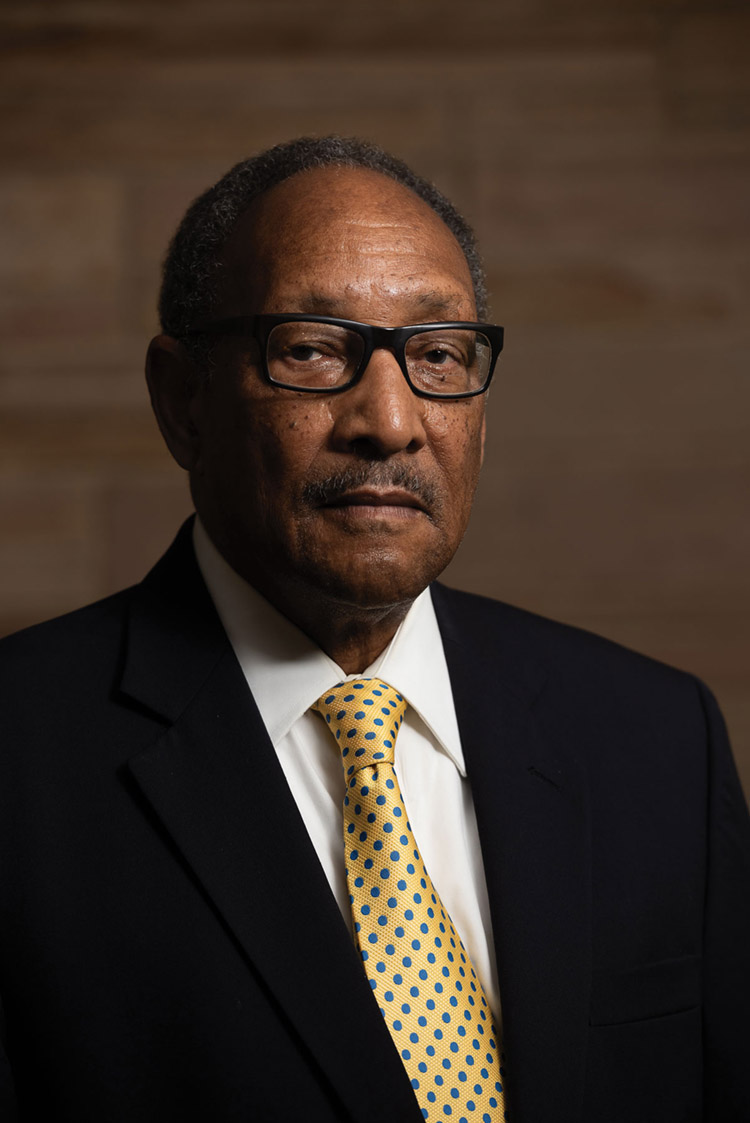

Bill Robinson: Advocating for civil rights since the summer of ‘64

Bill Robinson: “During the ’50s, you had to read your Jet magazine. Thurgood Marshall often had a column at the end.” Photo by David Hills Photography/ABA Journal.

For many young volunteers, the long hot summer of 1964 marked the beginning of a lifelong commitment to social justice. It was no different for Bill Robinson, who got involved in Mississippi’s Freedom Summer between his first and second years of law school. The injustice he witnessed while working to increase Black voter registration cemented his career path as a civil rights advocate.

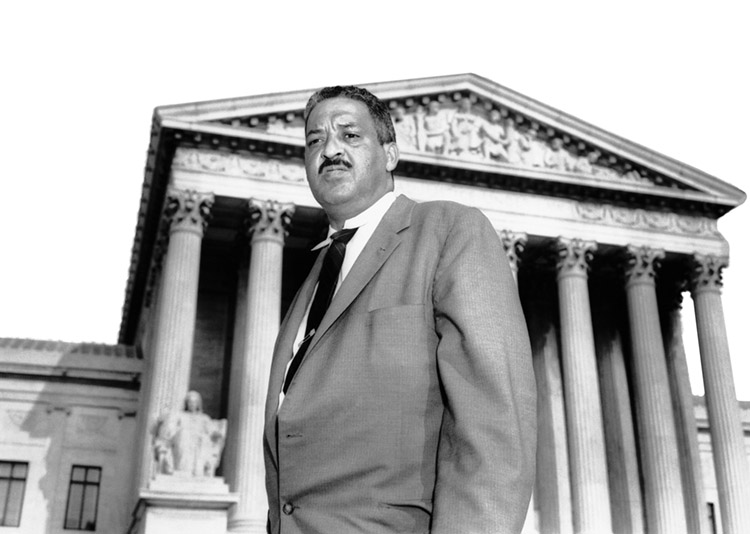

Robinson always knew he wanted to go to law school, inspired by a legal trailblazer in the African American community. “My hero was Thurgood Marshall. During the ’50s, you had to read your Jet magazine,” Robinson recalls. “Thurgood Marshall often had a column at the end, and I couldn’t wait to see what he had to say about what he was doing to represent us. That was always a motivating factor in my desire to be a lawyer.”

Robinson attended Columbia Law School, one of the many northern schools where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee recruited the best and the brightest to volunteer for the Freedom Summer project and join the civil rights movement. Unlike the recent Black Lives Matter protests, the civil rights movement of the ’60s was driven by coordinated events and strategies organized through top-down leadership structures.

“There were the bus boycotts, freedom rides and organizing done by Martin Luther King, [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], SNCC and [Congress of Racial Equality], and it was all targeted to specific kinds of change,” Robinson says. “Change in terms of public accommodation, and the goal was desegregation of facilities, and you had the student demonstrations—sitting at lunch counters.”

Thurgood Marshall. Photo by Bettmann/Contributor via Getty Images

During the civil rights movement, there were protests, lawsuits and legislation with clear goals to dismantle institutional racism, building momentum to support legislative change.

Robinson became part of the momentous movement toward equality under the law. He worked for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, litigating cases ranging from school desegregation to housing discrimination. Robinson’s seminal appellate work with the NAACP, and before the U.S. Supreme Court, helped establish guidelines for proving discrimination under Title VII. He went on to work for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and as executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Robinson later became founding dean of what is now the University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law.

Robinson’s career has given him a 360-degree view of protest movements and the civil rights struggle. He notes the difference between the ’60s agitation geared toward specific goals and the widespread unrest that has gripped the nation since George Floyd’s death. Robinson does hope the activism will result in concrete actions. “Once you get beyond criminal justice reform, I don’t see goals that will attack the systemic injustice that results in African Americans having a much higher rate of death and contraction of [COVID-19], for example.”

The current movement, Robinson says, has garnered more widespread and diverse support than the civil rights movement of the ’60s.

“Even though we were successful in getting momentous legislation passed, corporations did not step up and speak out and give money to support civil rights in the ’60s and ’70s in the way they have quickly done so in response to the current movement.

“I think it’s going to be more than a moment—there’s too much support from too many sources.”

—Liane Jackson

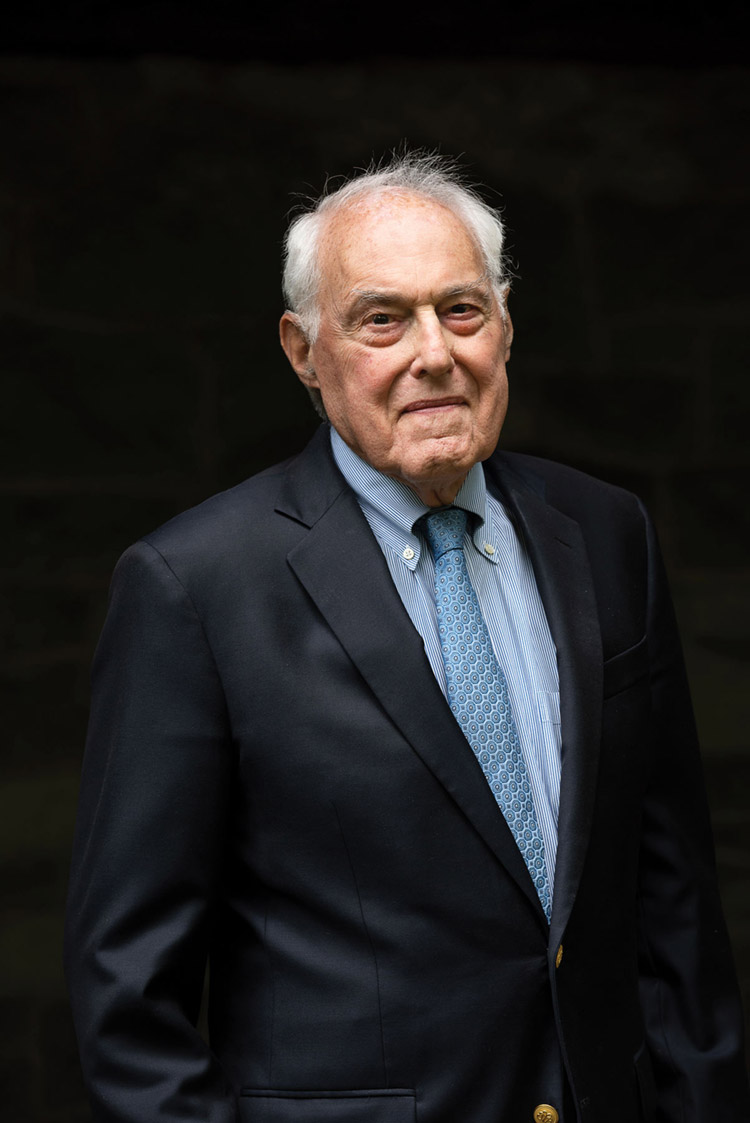

Stephen Pollak: Ensuring safe passage for civil rights marchers in Selma

Stephen Pollak: “I think we … saw a lot of progress and probably were not as conscious that there was so much more to do.” Photo by David Hills Photography/ABA Journal.

In 1965, Stephen Pollak, a civil rights lawyer with the U.S. Department of Justice, was ordered to pack his suitcase and get on a jet to Selma, Alabama, after state troopers and sheriff’s deputies attacked marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge on what became known as Bloody Sunday.

Pollak, who was first assistant to the assistant attorney general in charge of the department’s Civil Rights Division, was dispatched to ensure local officials honored a federal court order allowing the marchers to proceed to the state Capitol in Montgomery in support of voting rights for Blacks. Later, a second group of protesters, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., would be protected by federalized National Guard troops.

“I met with the leaders of the march to understand what their plans were and understand what they were doing to ensure the safety of the marchers,” Pollak recalls. “We prepared for possible interference.”

Pollak and his colleagues worked with police and the National Guard to make sure they followed the court order. “I recall the large numbers of people who were coming into the city and how momentous it was to observe that, and to observe that go on peacefully,” Pollak recalls.

The march indeed proved momentous, leading to passage of the Voting Rights Act. Pollak participated in negotiating the final draft of the act with Sens. Mike Mansfield and Everett Dirksen. He also worked to dismantle governmental policies that supported segregation and inequality.

“The mood then, as far as the law, was to eliminate the state governmental barriers to equal rights, and great progress was made in doing that,” Pollak says. “I think we who were part of the effort to advance against government-supported discrimination saw a lot of progress and probably were not as conscious that there was so much more to do.”

Marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Bettmann/Contributor via Getty Images.

Recent demonstrations across the country show there is much more to do. Protests—some resulting in violent clashes with police—are reminiscent of those in the ’60s, but Pollak sees significant differences. “What has developed in the years after is an understanding that limitations on equal treatment, equal access and equal opportunity go well beyond the governmental barriers, and the demonstrations today are addressing those issues,” he says.

Like many, Pollak, of counsel at Goodwin Procter in Washington, D.C., wonders whether current events reflect a moment or a movement. “There’s been a lot of writing to say that the current movement to extend rights and opportunities is more than a moment. I hope it is. I support it,” says Pollak, a member of the ABA Senior Lawyers Division. “But change is always difficult. There seems to be more staying power. But this sort of thing is always in the balance, so we’ll see.”

He also notes a lack of identifiable leaders of the current movement.

“One of the interesting things is that in the ’60s, there were personal leaders of the movement—people like Dr. King, people around Dr. King, leaders like Roy Wilkins and Vernon Jordan,” Pollak notes. “Today, the movement is more broad-based and is less identified with its leadership. Whether that’s a strength or a weakness, I don’t have the answer.”

Leadership aside, the movement seems to have more support. “There are encouraging signs that the population is not limited to minorities, and it has extended out to other segments that support the efforts to eliminate the causes and effects of racism,” Pollak says.

—Kevin Davis

Margaret Burnham: Dedicated to civil rights and restorative justice

Margaret Burnham getting sworn in as the first black female judge in Massachusetts history to the Boston Municipal Court by Gov. Michael Dukakis in August 1977. Photo courtesy of the Boston Globe Library collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

In the early 1960s, Margaret Burnham put her undergraduate college education on hold to fight for social justice in the South. She left New York for Mississippi to join the SNCC in its efforts to combat the disenfranchisement of Black voters who faced intimidation, interference and violence.

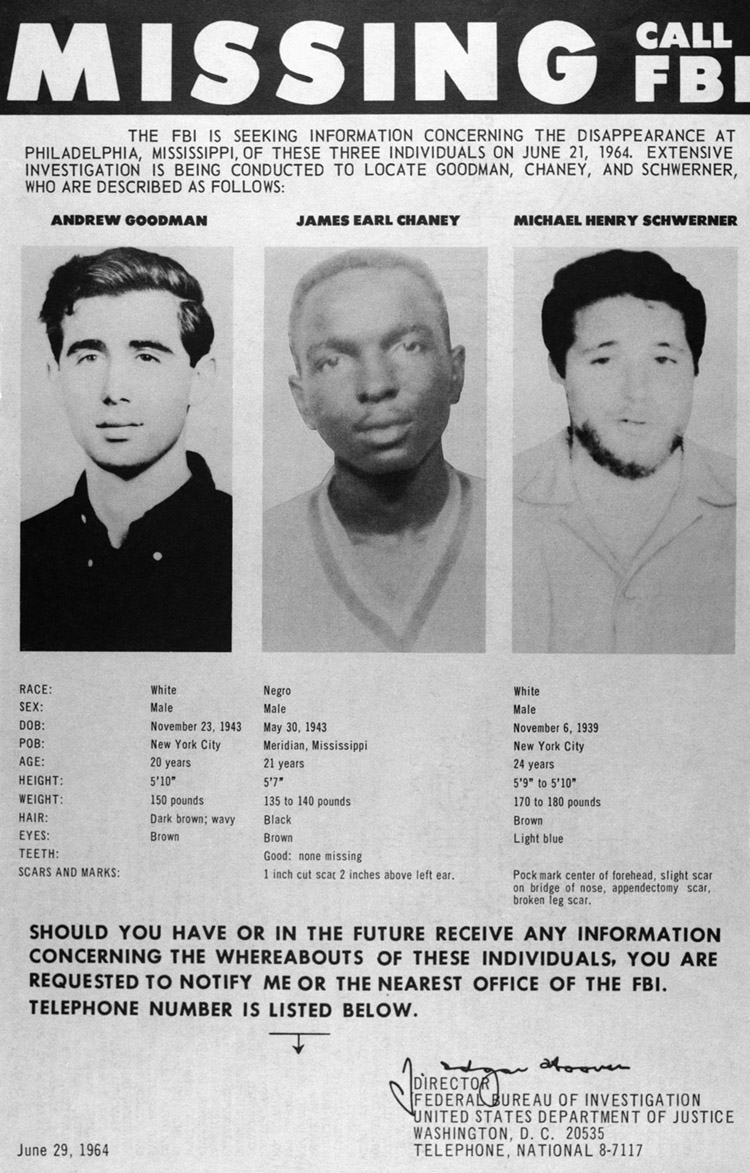

During the summer of 1964, three of Burnham’s fellow Freedom Summer workers who investigated a local church burning—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner—were shot and killed by a Ku Klux Klan mob.

“We were young, and while we understood the dangers under which we were all working and under which Mississippians had worked for many years before we got there, this really sort of brought it home to all of us like a thunderclap,” says Burnham, a professor at Northeastern University School of Law and founder and director of its Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project. According to Burnham, the project is “meant to articulate the through-line from the routine, hegemonic racial violence of the Jim Crow era to today’s lethal policing that so disproportionately devastates Black and brown communities.”

Prosecutors ultimately charged 18 people, including local law enforcement officers, with violating federal criminal civil rights statutes. Seven were convicted.

Burnham’s experiences then have served as a bridge to her legal career and to her current work in social justice—work that remains relevant today as the killing of innocent and unarmed Black people continues.

More than 40 years after working in the South, Burnham filed a civil rights case on behalf of the families of two young Black men: Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore, who in 1964 were kidnapped and murdered by members of the KKK in Franklin County, Mississippi. James Ford Seale, a reputed KKK member, was convicted on counts of kidnapping and conspiracy in 2007 after the case was reopened.

Burnham sued Franklin County, alleging law enforcement failed to intervene to prevent the young men’s deaths. She argued that the county’s collusion with the KKK resulted in lax law enforcement, allowing the Klan to commit violence against Black people with impunity. The case was settled for an undisclosed amount.

“It gave me an opportunity to close the circle and render an important legal service to these families and to the communities that cared about these two young men,” Burnham says. “And also it gave me an opportunity to see how far we could stretch current law to cover these old travesties.”

She used the funds to build CRRJ. Her organization researches and supports policy and educational initiatives on anti-civil rights violence in the United States between 1930 and 1970.

Burnham draws parallels between Dee and Moore’s deaths and the killing of George Floyd at the hands of police. “It’s not 1964 in that there are more avenues for redress today for victims of police killings,” she says. “But it is still the case that oftentimes these cases can get lost, buried, mistried, misprosecuted [and] underinvestigated.”

The events following Floyd’s death, she says, are part of a new movement, evidenced by the breadth and diversity of those involved and by those beginning to question what they know about racial inequity.

Burnham says these older cases and deaths are important to a public hungry to understand how we got to where we are today. “Unless we unearth in some detail—we take the time to explore the truth—we’ll never be able to identify lasting solutions today,” she says. “You gotta face it to fix it.”

—Blair Chavis

Steven Winter: Setting a legal standard for police use of deadly force

Steven Winter: If police were to get the proper tactical training, these cases could be avoided.” Photo by Wayne Slezak/ABA Journal.

Steven Winter was just 31 years old when he argued a landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court that would establish stricter standards for police use of deadly force. It’s a case that resonates strongly with him today because it involved the shooting of an unarmed Black teenager.

Winter, a lawyer with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund at the time, represented the father of Edward Garner in a civil rights case against the state of Tennessee. In 1974, police in Memphis were dispatched to investigate a report of a prowler. An officer who spotted Garner in a backyard warned him to halt and then shot him in the back of the head as he tried to scale a fence. The boy, 15, had stolen a purse and $10.

At issue was a Tennessee statute dating to 1858 that codified the common law “fleeing felon” rule that officers could use deadly force to “effect the arrest” of any fleeing felon, says Winter, now the Walter S. Gibbs Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at Wayne State University Law School. At the time, 18 other states had similar statutes, and four others applied the common law rule. Most police departments in major cities had policies that were more restrictive than state law.

Winter successfully argued the case on appeal before the Cincinnati-based 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 1983. The court ruled that the law violated the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable seizure—in this case, the apprehension of an unarmed criminal suspect by use of deadly force. It upheld a previous ruling in the 6th Circuit that the Tennessee statute was unconstitutional because it authorized unnecessarily severe and excessive and therefore unreasonable methods of seizure of the person under the Fourth and Fourteenth amendments.

The high court in 1985 ruled 6-3 in Winter’s favor in Tennessee v. Garner. “The use of deadly force to prevent the escape of all felony suspects, whatever the circumstances, is constitutionally unreasonable,” Justice Byron R. White wrote. “‘A police officer may not seize an unarmed, nondangerous suspect by shooting him dead.”

States soon began changing their laws. “People in the law enforcement community paid serious attention to it,” Winter says.

But the recent killings of unarmed Black people at the hands of police remind Winter that laws alone cannot save them. “When I watch these things, it’s with terrible sadness. I think, ‘That didn’t need to happen,’” Winter says. “The officers could have followed more professional standards, employed different tactics and avoided putting themselves in a position where they were—or might have thought they were—in danger.”

It comes down to training. “If police were to get the proper tactical training, these cases could be avoided. And that better training would over time affect the underlying police culture, which I think is at the root of the problem,” says Winter, a member of the ABA Senior Lawyers Division. “It’s all about police culture. Unless you change that, nothing changes. And the only way to change that is through very systematic and determined efforts.”

After he won in the Supreme Court, Winter called Cleamtee Garner, the boy’s father, with the good news. He explained that the case for civil damages, however, was far from over. “I said it could be many years before you ever see any money in this,” Winter recalls. “He said to me, ‘I don’t care about money. It’s not about the money, just so that they don’t shoot any more Black kids.’”

Cleamtee Garner died before the case was settled in 1995. The family received $300,000.

—Kevin Davis

John Burris: Fighting against police misconduct and excessive use of force

John Burris: “After Rodney King, I received a lot of calls around it because people were not prepared to accept the notion that police would act in such a brutal way.” Photo by Tony Avelar/ABA Journal.

Rodney King: “Can we all get along?” Photo by AP Photo/David Longstreath

Rodney King’s iconic plea for unity after video of his savage police beating went viral in 1991 has renewed resonance today. “Can we all get along?” King asked after the acquittal of the four Los Angeles Police Department officers responsible for the attack provoked five days of riots across the city. King’s would become the first in a long line of caught-on-tape stories of unprovoked police brutality against Black men and women. It’s a familiar narrative in 2020. But almost 30 years ago, King’s assault shocked many—just not those in the Black community.

“Before Rodney King, I had a lot of police cases with no video, and they were very challenging cases,” says attorney John Burris, who represented King in his civil case against the Los Angeles Police Department. “There was the view of jurors that police were infallible, and my client must have done something wrong. After Rodney King, I received a lot of calls around it because people were not prepared to accept the notion that police would act in such a brutal way. It was the first time for the world to see. It was a real eye-opener.”

Burris has practiced law for more than 40 years with a focus on police misconduct and excessive force cases. He represented the family of Oscar Grant, who was shot and killed by a Bay Area Rapid Transit police officer in Oakland, California, while lying face down and handcuffed in a subway station. That 2009 incident, captured on multiple cellphone videos, inspired the award-winning movie Fruitvale Station and galvanized the community. As the result of another sweeping police brutality case Burris filed, known as the “Oakland Riders” lawsuit, the Oakland Police Department went under federal oversight, and the city has seen a reduction in use-of-force cases. But Burris notes that’s just one jurisdiction out of thousands. And despite the nationwide protests against police killings, Burris says, so far, little has changed.

“George Floyd stopped nothing. Right after George Floyd was killed, there were two police shootings here involving young Hispanic boys,” both in their early 20s, Burris says. “There was no George Floyd effect there. I think that some departments are just wildin’ and on the loose, if you will, out of control.”

Under President Donald Trump’s administration, there have been reductions in federal oversight and “pattern and practice” cases against rogue police departments, and without public pressure and political will—particularly at the local level—little can change, Burris says. He’s been suing some of the same departments for decades.

“I tell people who are protesting, ‘Is it a moment or a movement?’ It’s clearly a moment now of protesting and Black Lives Matter—and all that’s important. But the question, though, is what happens when the marching has to stop? You’ve got to have a plan.”

Looting and rioting ensued in Los Angeles after four police o’cers were acquitted in the Rodney King trial. Photo by Ted Soqui/Corbis via Getty Images.

Burris says activists need to advocate for body cameras, internal affairs reviews, citizens reviews and independent boards, along with an end to one of the most endemic and pernicious abuses of police power: racial profiling.

“The vast majority of the policing is not shooting people—it’s the stops, it’s the searching of the car, the handcuffing, throwing people on the ground. It’s putting criminal records on you when you don’t deserve it. Charges of resisting arrest. That’s where real reform needs to take place, that’s how you ruin people’s lives on a daily basis.

“Those are things you’ve got to have in mind at the end of the march.”

—Liane Jackson

John Rosenberg: Fighting discrimination for half a century

Attorney John Rosenberg points to himself in a photo of the 1966 Civil Rights Division at the U.S. Department of Justice. Attorney Stephen Pollak is in the front row, eighth from right. Photo by David Mudd Photography/ABA Journal.

John Rosenberg has always been a fighter, so from his perspective, the massive Black Lives Matter protests are part of a necessary and ongoing struggle for civil rights in America. As a young Jew in Nazi Germany, Rosenberg managed to escape with his family to a new life in America. Once in the U.S., he devoted his life’s work to uplifting the marginalized and to the struggle for equal rights.

Rosenberg, 88, has been a civil rights attorney for more than 50 years. He arrived in New York City in 1940 at age 8, after his family survived Kristallnacht and his father’s release from a concentration camp in Buchenwald. The family eventually settled in South Carolina.

Rosenberg was no stranger to discrimination; he had grown up in the segregated South, and that experience had impacted his outlook. He points to a time in the U.S. Air Force during the mid-1950s when he and his African American friend and fellow officer, Abe Jenkins, returned to the U.S. and took a train to see their families. Jenkins had to ride in the back of their train in Washington, D.C. Rosenberg says that moment had a lasting impact and helped feed his desire to go to law school and fight injustice.

John Rosenberg helped prosecute the 1964 Freedom Summer case involving civil rights workers who were killed. Photo by Bettmann / Contributor via Getty Images

“That was something I had not forgotten,” Rosenberg says, adding he “hoped to have some part in trying to undo this caste system that was going on” in the South. Becoming a lawyer gave him the opportunity. As an attorney with the Civil Rights Division at the U.S. Department of Justice from 1962 to 1970, Rosenberg fought discrimination and segregation and played an integral role in protecting Black voting rights in the South.

The current protests against police killings are reminiscent of Rosenberg’s work during the civil rights movement decades ago. In 1963, Rosenberg secured a key witness in a historic police brutality case involving voting rights advocate Fannie Lou Hamer and other activists who were viciously beaten in jail after traveling and eating in a designated whites-only area of a bus depot in Winona, Mississippi. The legal team lost the case, but Rosenberg recalls, “This was an early prosecution of that sort.” He adds, “It did show the [police] department would do something in these situations.”

In 1967, Rosenberg was a member of the team that prosecuted the notorious Freedom Summer case U.S. v. Price, along with his boss, Assistant Attorney General John Doar. Three civil rights workers—James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner—were murdered in Mississippi. Rosenberg worked on investigations for the case, which inspired the 1988 film Mississippi Burning. Eighteen defendants, including Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, ultimately were indicted.

Reflecting on how far the country has come from the violence of the 1960s to George Floyd’s death in May, Rosenberg says there is still a long way to go, though he’s hopeful. “I think the work we did in the courts was a good start. “There is a real feeling that we have to understand each other, and that systemic racism is a problem for all of us,” Rosenberg says. “What we’re talking about with the protests really is our humanity, and can we create a just society?”

—Blair Chavis

This story was originally published in the October-November 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Moment or Movement? Lawyers involved in civil rights battles reflect on recent demands for racial justice”