Law school debt is delaying plans for recent grads

Photo illustration by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

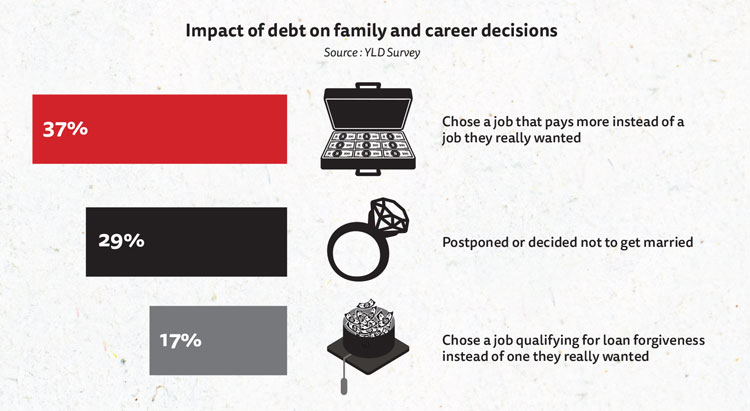

Some new attorneys delay buying a home or a new car. Others reluctantly postpone marriage and having children while altering the career plans they had going into law school.

These are among the personal and professional sacrifices young lawyers often make due to their sizable student loan debt, according to a survey conducted this spring by the ABA’s Young Lawyers Division and the ABA Media Relations and Strategic Communications Division. Many survey respondents also provided open-ended comments indicating their student loans have contributed to mental health issues, including anxiety and depression.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

The survey results were highlighted in the ABA’s second annual Profile of the Legal Profession—a data-driven deep dive into issues facing attorneys and the legal industry. The section on student debt was among the new additions, as was information about the country’s legal deserts. (See “2020 state of the profession report shows dearth of lawyers in rural areas, attorney debt struggles” at ABAJournal.com/2020profession.)

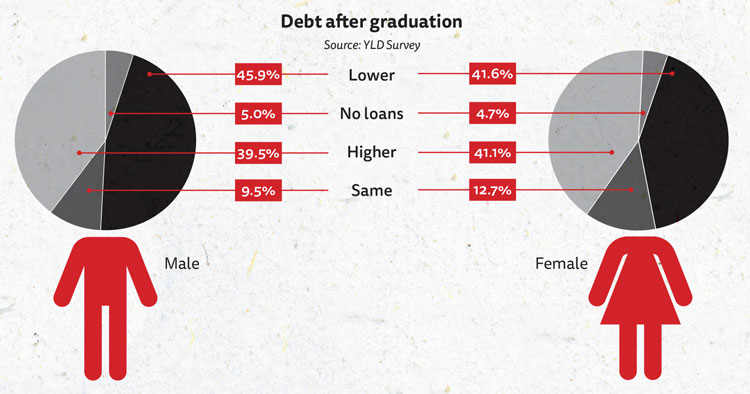

According to the YLD survey of 1,084 attorneys, whose median age was 32, the costs of legal education are skyrocketing. Participating attorneys reported carrying a median cumulative student debt of $160,000, with roughly 40% stating that their debt load is higher now than when they graduated from law school.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

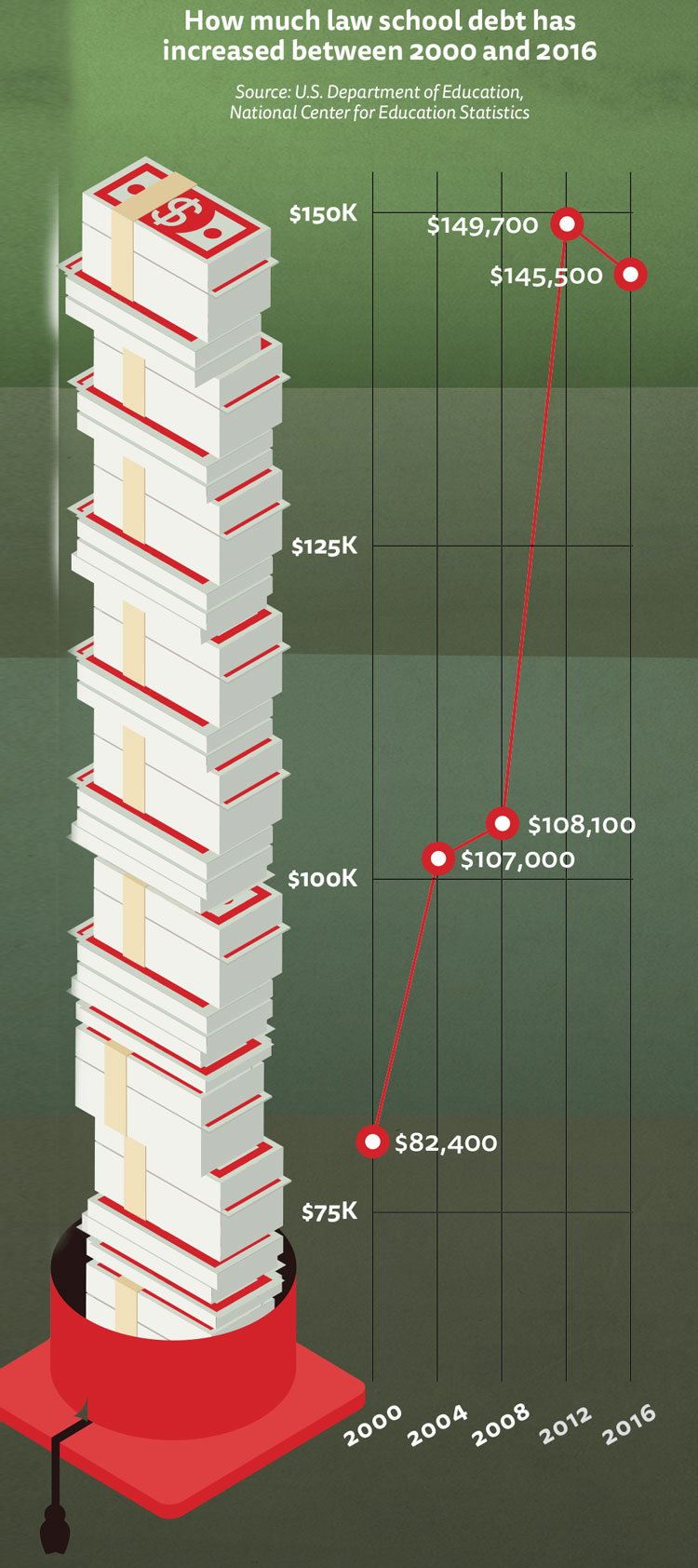

Additionally, U.S. Department of Education data referenced in the Profile of the Legal Profession indicates the average cumulative student debt for law school graduates rose from $82,400 in 2000 to $145,500 in 2016, the most recent year for which such federal data is available.

“That should bring a renewed focus for the legal profession on the cost of legal education,” says Christopher Brown, chair of the YLD.

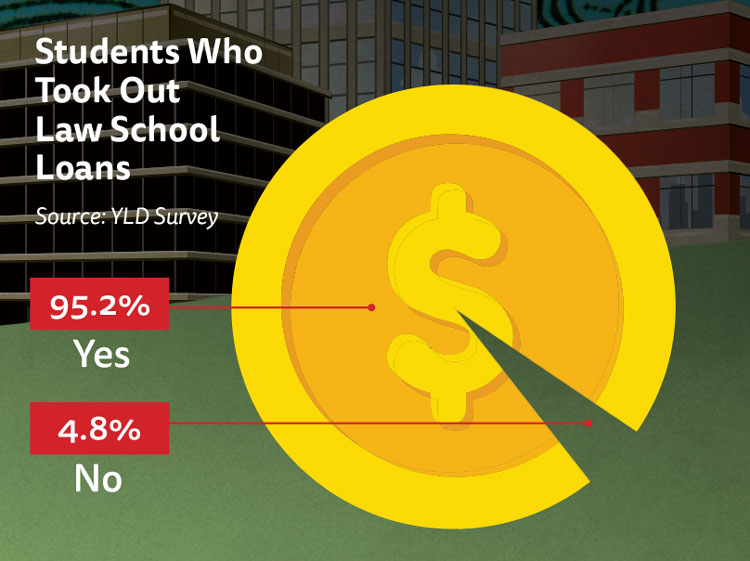

The YLD tapped AccessLex Institute to delve even deeper into the student debt information gathered from the survey of newer lawyers. The YLD/AccessLex Institute report, which was released Oct. 26, found that over 95% of respondents took out loans to attend law school, and that debt affected men and women almost equally. See ambar.org/debt for more.)

Brown is particularly hopeful the survey data will lead to a larger number of more experienced attorneys realizing law school debt is a “systemic problem” that they should devote energy toward addressing.

Meanwhile, he says the YLD’s Student Loan Debt and Financial Wellness Team is working with the American Bar Endowment to provide resources to young lawyers to help them successfully overcome their financial challenges.

The YLD also recently established a holistic Wellness Team to assist members grappling with mental health and substance abuse issues, including those brought on by student debt.

“We wish that the stress of our financial lives could stay in our bank accounts, but it doesn’t,” says Brown, deputy law director for the city of Mansfield, Ohio.

In recent months, the ABA Journal interviewed six young lawyers about how their debt burdens influenced their personal and professional journeys.

They described a fair amount of stress related to student loans. But they also showed a lot of resilience, with narratives about how they are making do and advancing professionally, even amid a global health pandemic.

These are their stories.

Photo of Katrina Castillo courtesy of Katrina Castillo; Getty Images

Katrina Castillo

Katrina Castillo, a 2013 graduate of Indiana’s Valparaiso University Law School, told her boyfriend about her law school debt about a year after they began dating.

“We started talking about how much I had left, so I logged into my account and it was $325,000,” says Castillo, who also has an LLM from American University Washington College of Law. “He almost had a heart attack.”

He calmed down after she explained that she was enrolled in the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program.

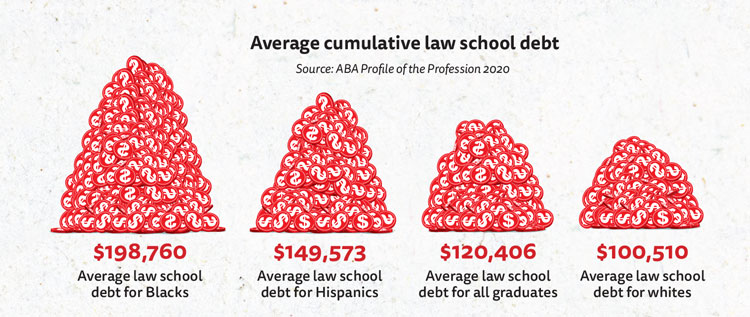

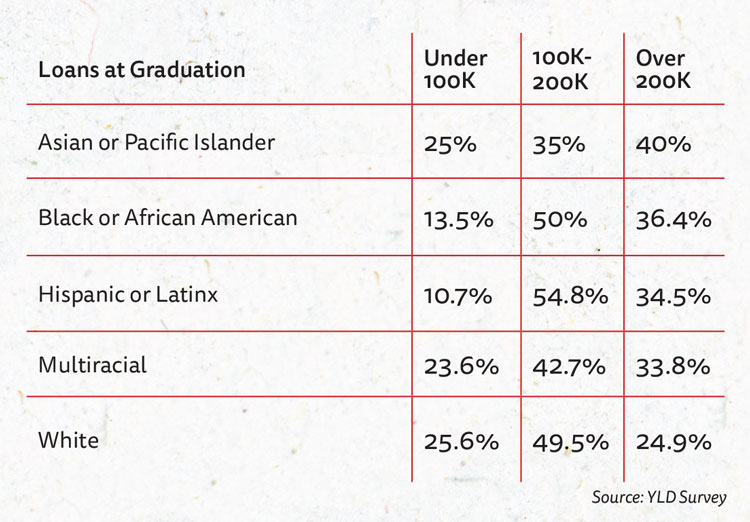

“It was bad, but not as bad as it sounded,” explains Castillo, who is Latina. Hispanic, Black, Asian and multiracial law school graduates take on far higher debt loads than their white counterparts, according to the ABA YLD survey.

She is also enrolled in an income-based repayment plan, and all of her school debt is from law school and the LLM program. Castillo’s boyfriend is now her fiance, and the couple recently moved from Arlington, Virginia, to New Delhi for his State Department job as a foreign service officer. Castillo, who had been a decision writer with the Social Security Administration, now works as a political associate with the U.S. Embassy.

She grew up in a military family, and says joining her fiance in India was not a hard decision to make.

“At this point, everywhere in the world is up in the air,” she adds.

Having a government job will keep her in the PSLF program. But for now, she has no student loan payments because the federal government in March suspended them for everyone until the end of 2020. The administrative forbearance is part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, and in August, President Donald Trump directed the U.S. Department of Education to continue loan forbearance until Dec. 31.

Castillo expects to have her student debt discharged in about five years through the PSLF program.

“I am going to throw a party, it’s going to make me feel better, just the fact I will be done,” she says.

But the future of PSLF still remains a worry for Castillo and others. Since it was introduced as part of the 2007 College Cost Reduction and Access Act, the program has faced various defunding threats, and there have been problems for people who thought they qualified for it but did not.

In 2016, the American Bar Association sued the U.S. Department of Education after it changed its interpretation of PSLF regulations. Four lawyers, two of whom had worked at the ABA, were also plaintiffs in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia action. In 2019, a federal judge found that the department rule changes were arbitrary and capricious, and the action settled in 2020 after the agency agreed to recognize ABA employees as public service workers who are eligible for student loan forgiveness.

“Every time a story comes out about it, I definitely get a little bit of anxiety,” Castillo says.

She now lives in an apartment paid for by the State Department and says the cost of living is cheaper in New Delhi than it was in the Washington, D.C., area.

“It’s definitely a weight off because we don’t have some of the same bills we did,” adds Castillo, who is also enrolled in an income-based repayment plan. Before she left her Social Security Administration job, her monthly student loan payment was roughly $500 per month. If she weren’t in an income-based repayment plan, it would have been $3,000, which was more than her take-home pay.

“I would be in a ball crying every day if I didn’t have it,” Castillo says.

Photo of Kaitlin E. Preston by Earnie Grafton; Getty Images

Kaitlin E. Preston

While attending Thomas Jefferson School of Law in San Diego, Kaitlin E. Preston thought of working in the nonprofit sector once she became a licensed lawyer, she says.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

But after graduating in 2016 with roughly $240,000 in student debt, Preston decided she would need to work at a law firm to help her pay down her loans.

Amid the competitive legal market in Southern California, Preston says she was fortunate to secure a job handling real estate issues at McCarthy & Holthus in San Diego with a starting salary of approximately $65,000.

Nonetheless, Preston and her husband determined they wouldn’t be able to buy a home as soon as they wanted given their financial circumstances. They also put off having kids.

“In the beginning of your legal career, you kind of have all these ideas of ‘I’m finally where I wanted to be, and I’ll be able to do so many things,’ without the later realization that ‘I need to pay down some of the student loan debt so that I can afford to do these things,’” says Preston, 30.

She also says hearing about the cost of day care in San Diego played a role in the decision she and her husband made to delay having children.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

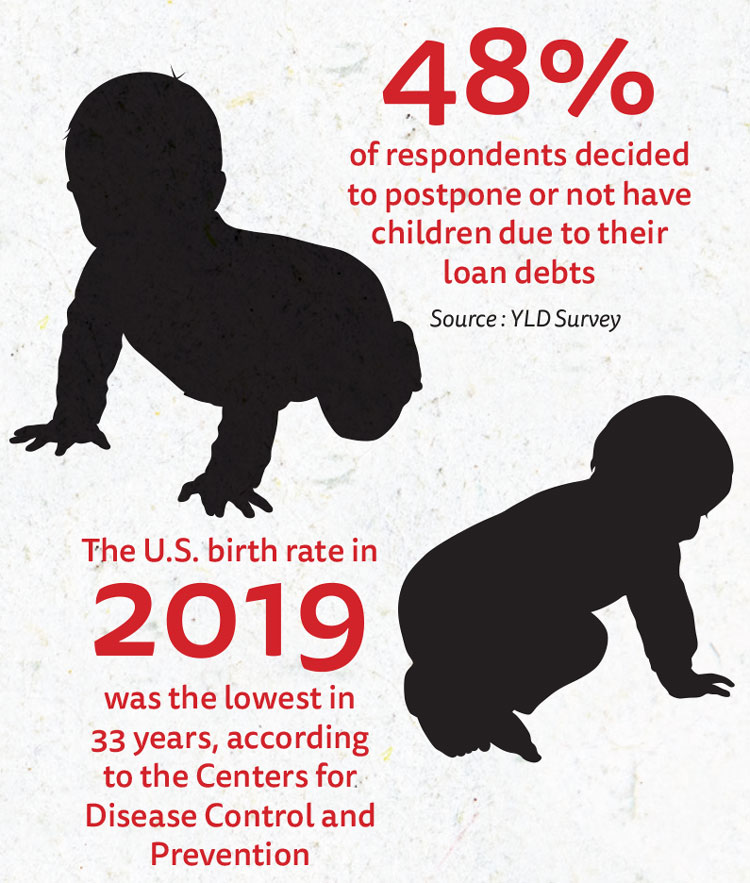

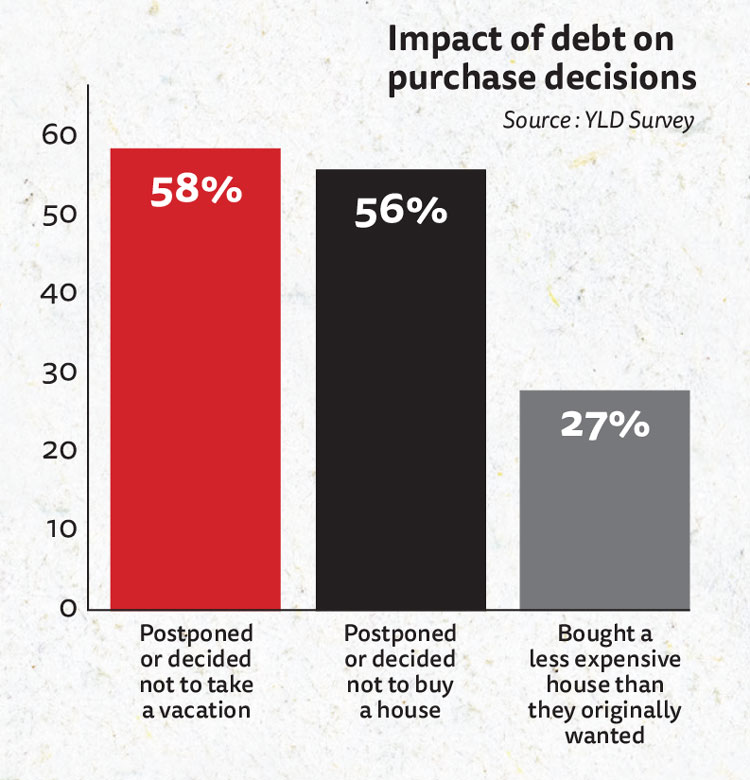

They are hardly alone on that front; the ABA survey found that nearly 50% of respondents decided to postpone or not have children due to their loan debts. Additionally, the U.S. birth rate in 2019 was the lowest in 33 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preston says postponing the home purchase was much more difficult than delaying having children with her husband, who works in the hotel industry. The couple enjoys hosting family and friends, but they find it difficult to do so in a one-bedroom apartment.

“At a certain point in your life, you want to buy a home and enjoy that space,” Preston says.

As for her legal work, Preston has practiced civil defense litigation in San Diego at two other firms since her first gig. Her second legal job was at Selman Breitman, where her starting salary was $115,000. She currently works as an attorney at Haight Brown & Bonesteel and declined to provide her starting salary there.

Photo of Jay R. Thakkar by Ben Van Hook; Getty Images

Jay R. Thakkar

After graduating from the University of Florida Levin College of Law in 2010, Jay R. Thakkar secured a job in the Sunshine State with the Office of the Public Defender for the 18th Judicial Circuit.

Though he was thrilled to land a legal position amid a tough economic climate, Thakkar’s starting salary as an assistant public defender was $42,000. Meanwhile, he had finished law school with roughly $130,000 of student loan debt.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

As a result, Thakkar says he could not afford to get his own place to live and made the tough decision to move back in with his parents in Melbourne, Florida.

“I just graduated law school, and I’m basically back in the room I went to high school in,” he says. “It felt like I didn’t progress much.”

According to a 2019 report from Zillow, 21.9% of millennials live with their parents—10.2 percentage points higher than those in the same age group in 2001.

Thakkar also had wanted to purchase a new car soon after law school but says he had to delay doing so to pay down his loans. Instead, he kept his Scion tC that he had driven since his undergraduate days.

“I didn’t want to live on credit card debt because I already had debt,” says Thakkar, who is of Indian descent.

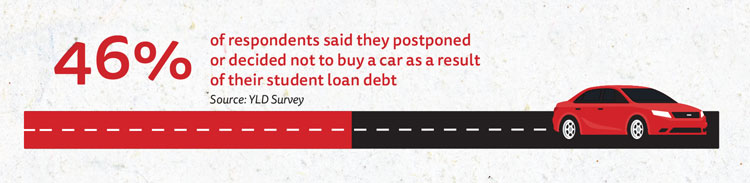

According to the ABA survey, 46% of respondents said they postponed or decided not to buy a car as a result of their student loan debt. Additionally, 33% of respondents said they had to settle for a less expensive car than the one they originally wanted.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

Thakkar lived very frugally during his time working for the public defender’s office from late 2010 to early 2012 while attempting to quickly pay off his loans.

He was then hired to work at the Cantwell & Goldman law firm in Cocoa, Florida.

The position came with a significantly higher salary and allowed him to handle both criminal defense work and civil litigation.

Several months into his new job, he was in a financial position to get his own apartment, Thakkar says.

He later was named a partner at his firm, got married and bought a home.

He also purchased a new car after logging more than 150,000 miles on his Scion.

“I got a luxury car, but it was a used luxury car,” says Thakkar, who serves on the Florida Bar Young Lawyers Division’s board of governors.

The 35-year-old says he and his wife, who works in marketing/communications, are expecting their first child early in 2021.

Photo of Cheyenne N. Chambers by Albert Dickson; Getty Images

Cheyenne N. Chambers

Cheyenne N. Chambers’ student debt is slightly less than $200,000, but she says it doesn’t control her life. She’s a homeowner with three savings accounts: one she uses to fund self-care and day-to-day expenses; another is for retirement, which is separate from her 401(k); and a third has six months’ worth of emergency funds.

The Ohio native graduated in 2014 from Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, and some of her money also goes back to the institution via an annual $750 merit scholarship she gives to Black students.

Budgeting, the North Carolina-based appellate lawyer says, is part of her goal-setting, and she religiously tracks every dollar she spends or saves in a notebook.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

“Some people may feel really down or disappointed about their circumstances, but I look at it as a challenge,” says Chambers, 31. “I look at the notebook, and I really try to figure out ways to get another $25 in my savings account. That’s just how I am as a person.”

After graduating from law school, Chambers moved with her parents to North Carolina. She lived with them while working as a first-year associate at the Charlotte office of Moore & Van Allen so she could save money for living expenses the next year, when she moved to Pasadena, California, and clerked for 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Paul Watford. The monthly rent for her one-bedroom Pasadena apartment was $2,000, and her clerk salary was in the high five figures.

Large law firms solicit federal clerks for associate jobs, and Chambers initially thought she’d take that path so she could pay off her student debt quicker. But the firms she spoke with seemed more interested in hiring her for their trial groups rather than appellate practices. Also, as a Black woman, she noticed there were few people who looked like her in the appellate practices.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

So Chambers is now an associate with Tin Fulton Walker & Owen in Charlotte. She is enrolled in an income-based repayment plan for her student loans. She would not share her annual salary or the amount of her monthly loan payment.

Working at a smaller firm offers more opportunities to pursue the career she wants, says Chambers, who also serves as co-chair of the ABA’s Section of Litigation Appellate Practice Young Lawyers, Membership and Diversity subcommittee.

“I wouldn’t say my student debt has tremendously influenced my life decisions,” she says, “but I’ve thought about my choices a lot longer and more carefully because of my student debt.”

Photo of Samuel A. Segal by David Hills; Getty Images

Samuel A. Segal

Samuel A. Segal vividly recalls a student loan exit interview after graduating from law school at which he was told he had accumulated $105,000 of educational debt.

“I remember looking at the final number and thinking, ‘This must be some sort of error in the math,’” the 2010 Northeastern University School of Law grad says. “I was going to have a $1,000-a-month payment on my loans. It was a pretty harrowing time.”

Segal also remembers thinking he would make upwards of $150,000 in his first legal job after graduation. Instead, his starting salary at a small firm in Boston was $55,000.

In light of his much-less-than-anticipated salary and sizable monthly loan payment, Segal says he could not afford to buy his own place and decided to remain in the apartment he rented during law school. While doing so, he ate a lot of pasta dinners and limited how often he went out.

“I had to keep living like a student for four years out of law school,” Segal says. “I put basically every spare cent I had toward those loans.”

Segal’s decision to delay purchasing a place is not an outlier; 56% of ABA YLD survey respondents said they postponed or decided not to buy a house because of their debts. Lawyers have made these choices amid rising home prices, and the National Association of Realtors reported that September’s national housing price increase marked 103 straight months of year-over-year gains.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

Segal, a past chair of the Massachusetts Bar Association’s Young Lawyers Division and a district representative to the ABA YLD in recent years, says he also had to put off purchasing a car while working to pay off his loans. If his boss needed him to go to court, he would use a Zipcar.

“My parents kept asking me, ‘When are you going to get a car?’” Segal says. “A car was luxury I could not afford.”

It was nearly five years after graduating from law school when Segal says he paid off his student loans and progressed to a financial position where he could start making major purchases. That led to Segal buying his own place to live and purchasing a car.

Segal, a 35-year-old who specializes in personal injury cases, also started his own law practice roughly five years ago. He says his income has steadily grown from $60,000 in his first year to $267,000 last year. Additionally, he closed on a new office purchase in late September.

“I’m working on the expansion plan,” Segal says.

Photo of Victoria B. Finlinson by Benjamin Hager; Getty Images

Victoria B. Finlinson

Victoria B. Finlinson graduated from law school with $70,000 in student loan debt and an $800 monthly payment.

It was a 10-year loan, but the 2014 graduate of the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law paid off the debt in half the time by making larger-than-required payments.

It was a big sacrifice but worth it, she explains. Finlinson is a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and says part of the faith’s culture is not having debt.

“This was something I thought about and said, ‘I can get this done,’” Finlinson says. “I wanted to be more secure.”

The past president of the Utah Bar’s Young Lawyers Division is an associate at Clyde Snow & Sessions in Salt Lake City. She says her annual salary is in the mid-six-figure range, and she is a litigator who handles employment matters.

Finlinson, 31, grew up in Modesto, California, and she chose her law school because it was top-50 ranked with low tuition. She stayed in Salt Lake City because she liked her law firm, and the cost of living was low.

Chart by Elmarie C. Jara; Getty Images

It’s also where she met her husband, a digital marketing specialist who just started an MBA program at Brigham Young University. They pay his tuition out of pocket and own a home about five minutes away from her downtown law office.

The couple has a 2-year-old son and pays $1,400 a month for day care at a facility that’s one block from Clyde Snow. Day care would be cheaper outside the city, Finlinson says, but the convenience makes the extra cost worth it.

Work, she adds, has been even busier than usual during the coronavirus pandemic.

She thinks today’s young lawyers have more stress factors than their predecessors because technology keeps them constantly tied to work.

Also, making partner is harder than it once was.

“I’m worried that firms will be less likely to advance associates because they’re concerned about the financial impact of the pandemic,” Finlinson says.

This story was originally published in the Dec/Jan 2020-2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Dreams Deferred: Law school debt is delaying plans for recent grads, and here’s how 6 are adapting.”