Lady of the Last Chance: Lawyer Makes Her Mark Getting Convicts off Death Row

Photo of Christina Swarns by Len Irish.

In what seems her natural state, Christina Swarns is as sweetly plainspoken and easygoing as a kindergarten teacher, which, decidedly, she is not.

Seated across a conference table in a corner-view meeting room on the 16th floor of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund offices in Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood, Swarns brightens another 100 watts when mentioning a collect call the day before from a client she helped get off death row four years ago—someone “near and dear to my heart.”

The caller, Raymond Whitney, is mentally disabled, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2002 in Atkins v. Virginia that, given evolving standards of decency, it is now cruel and unusual to put such people to death. Swarns and others proved to a judge that Whitney’s impairment met the Atkins test, and he is now serving a life term without possibility of parole.

“It broke his heart in court to hear all his friends talk about how dumb he is,” says Swarns, who brought the case with her in 2003 when she left the Capital Habeas Unit of Philadelphia’s Federal Community Defender Office to become director of the LDF’s Criminal Justice Practice. “We had it set so that when a witness was asked to tell us about Raymond, whoever was beside him would distract him, asking things like, ‘Raymond, did you see the Super Bowl last year?’ He’s a big Dallas Cowboys fan.”

“The judge kept reprimanding us, saying ‘You have to stop talking!’ ”

Up until that time, Swarns says, everyone in Whitney’s life had failed him. She and various experts came to that conclusion after scouring his history and school records.

“There were mentions that ‘he’s learning nothing’ and ‘something’s wrong’ screaming out from the records going back to kindergarten,” she says. “And nothing was ever done. He’s retarded, and he had some kind of brain injury—there was a massive seizure in prison and now he’s on meds. And he’s the sweetest human being.”

Asked about the crime that put Whitney on death row, Swarns, 44, simply says, “I don’t remember the details. It wasn’t good.”

Death penalty lawyers can’t dwell on such things. They hew to humane principles in seeking due process and equal justice for some who acted at the furthest fringes of human behavior—though sometimes they naturally bond with their clients in battles over the highest of stakes.

Something in that mix might be best summed up in a line from the movie made of Sister Helen Prejean’s nonfiction book Dead Man Walking, in which the nun tells a skeptical prison guard, “I’m just trying to follow the example of Jesus, who said that a person is not as bad as his worst deed.”

(For the record, Whitney was probably intoxicated as he entered an apartment in the middle of the night to rob the occupants. When confronted, he stabbed a University of Pennsylvania graduate student to death as the man’s new bride looked on. “After I kill him, then I am going to fuck you,” Whitney told the wife. Police arrived as he pulled the knife from the man’s chest after stabbing him 24 times.)

Swarns has been involved in seven post-conviction cases getting inmates off death row, with a leading role in several. Death penalty litigation is, as she puts it, “extremely collaborative,” so it is sometimes difficult to tease out a single lawyer’s impact.

There is significant impact, however, in the fact that few African-Americans are involved beyond trial level in death cases. “And there’s still a lot of swagger in post-conviction,” Swarns says with a smile as she invokes a code word for the male bastion.

There are few women at the job. She was particularly proud of the fact that a couple of years ago, all four lawyers in her criminal justice project were women and, she notes, all under 5 feet 4 inches tall: “I like the idea of little women kicking ass.”

She’s quick to laugh when delivering such sharp-edged observations, and displays a gentler spirit than the words in print might suggest.

Photo by Len Irish

FROM COIF TO COURT

In elementary school, Swarns was certain in her desire to someday be a hair stylist. But her mother wouldn’t have it, going so far as to enlist some who practice the art to tell the girl how awful it was to stand all day.

As a young teen in 1982, Swarns gained new certainty in a future as a lawyer after seeing The Verdict. In the movie, Paul Newman plays a washed-up, alcoholic attorney who gets emotionally involved in the case of a woman in a coma; without telling her family, he declines a hospital’s substantial settlement offer and goes to trial.

“And my parents were like, ‘Oh, yeah,’ and steered me to meet with some real-life lawyers to reinforce that,” Swarns recalls. “All I knew was that I wanted to be Thurgood Marshall. How to do that in practical terms was lost on me.”

Leaving the peaceful Staten Island, N.Y., enclave where she grew up, Swarns went in 1986 to Howard University in Washington, D.C.—one of the historically black colleges and universities—to study political science and prep for law school. Her older sister, Rachel, now a reporter with the New York Times, was there a year ahead. (A maverick younger sister would go instead to Hampton University, another HBCU institution.)

Their father, originally from North Carolina, had gone to Howard, where he met their mother, who came from Nassau in the Bahamas and was a student at what then was the District of Columbia Teachers College. He has had a career in real estate and she is a retired regional superintendent in the New York City school system.

One distinctly HBCU quality took hold with Swarns: “Howard really pushed us to thinking about making our work matter.”

Apparently even before graduating.

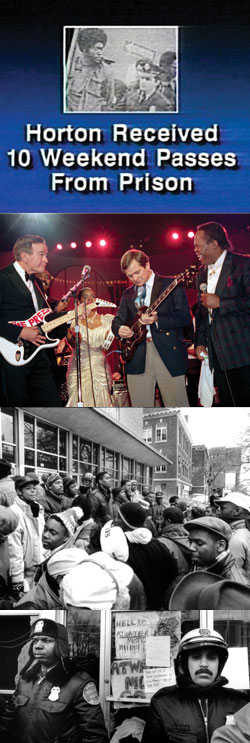

STUDENT ENGAGEMENT: One of the ubiquitous images of the 1988 presidential campaign was that of convicted felon Willie Horton, thanks in no small measure to Bush campaign manager Lee Atwater, who hammed it up on guitar with the newly elected president in January 1989 during inaugural festivities. But his appointment to Howard University’s board of trustees didn’t go over well with students, who stormed the school’s main administration building in one of the most spirited campus revolts since the Vietnam War. Photos: Bettman/Corbis, Rick Reinhardt, Jennifer Altman.

Swarns was in the milling crowds when Howard students protested the appointment of Republican dirty tricks operative Lee Atwater to the university’s board in 1989. Atwater had been George H.W. Bush’s presidential campaign manager the previous year, when the infamous Willie Horton ads featuring the black rapist-murderer’s mug shot helped defeat Democrat Michael Dukakis. Atwater was successful in his vow to “make Willie Horton a household name.”

Atwater was an accomplished blues guitarist on the side, having played with such greats as B.B. King. He thought his idea for a blues festival on Howard’s campus would captivate students. Instead, they gave new meaning to the old blues tune Stormy Monday, which had originally inspired King to take up the electric guitar.

It was on a Monday that Swarns joined more than 200 others in storming the administration building and taking it over. She called her parents from inside and told them that if she got arrested, check with Rachel about getting her out of jail.

“My parents, bless them, said, ‘Don’t you dare leave that building,’ ” Swarns recalls. “ ‘You stay right there and do what you have to do.’ ”

Within a few days, Atwater resigned, along with the university’s president, who had recruited him for the board. Swarns was featured in a Time magazine photo close-up of her and a friend in a face-off with a line of police officers.

Atwater died of a brain tumor two years later, and near the end he publicly expressed regrets, including in letters and phone calls to old foes, for his hardball political tactics and other distasteful endeavors.

Reminded of that, Swarns, who routinely deals professionally with aberrant behavior (and often at least some amount of absolution), is unforgiving of what Atwater wrought in race relations: “He had brain cancer, so you can’t be sure he meant it.”

SCHOLAR SEEKS NICHE

An exceptional student, Swarns probably had her pick of law schools. She went from the HBCU network to the Ivy League, enrolling at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. She liked the public interest requirement and worked on an AIDS law project and on street law at a community center.

But nothing clicked. Despite good grades, “I totally floundered in law school. I see all these applicants coming to me now with laser focus—I was not that kid. I didn’t know where my niche was.”

By December of her third year, Swarns was so uncertain she stopped interviewing. But she developed a plan: Move back in with her parents, take the New York bar exam and start interviewing lawyers about what they do or don’t like about what they do, and what practicing law is really like for them.

Oh, and do some volunteer work, maybe legal research, while she’s at it.

She called the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund and met with Elaine Jones, then the director-counsel and president—the first woman to hold the position. Jones asked what Swarns would like to do there.

“True to form, I said, ‘It doesn’t matter because everything you do interests me,’ ” Swarns recalls.

And for those who know Jones, true to form, the new boss dispatched the academically well-credentialed but green Swarns directly to where stakes are highest—the capital punishment project.

By the end of that first week in September 1993, Swarns was on the matter of a newly scheduled death warrant in Arkansas. She worked with the well-known LDF lawyers Dick Burr, George Kendall and Steven Hawkins.

“It was crazy,” she says. “For me it was terrifying. They got a stay, and I was like, ‘Whoa! This is amazing.’ It was, hands down, the most fascinating, riveting thing I’d ever seen.”

(The client was executed two years later. Today, because of Atkins, he would have gotten life without parole.)

Swarns didn’t have the courtroom experience required of an LDF hire, so she went to the Legal Aid Society of New York for a paying job to develop the skills—and then some. She had a client from Pakistan who offered a police officer cash when stopped for a traffic violation. Swarns put on a cultural defense, noting that in Pakistan such fines are paid on the spot. She didn’t get him off, but the judge was persuaded to levy only probation.

Then there was a long day of arraignments in a prostitution sting, one after another, with pimps in the courtroom ready with bail.

That evening, as Swarns walked along Broadway near Times Square in the theater district with a girlfriend and a partner from the friend’s law firm, a man across the avenue began hailing Swarns: “Yoo hoo! I love you! I love you!”

“This guy was out of central casting,” Swarns says. “He’s got the Jheri curl, got a sweatsuit. Here’s a pimp running at breakneck speed toward me and yelling, ‘You were wonderful! I loved you today.’ ”

She looked at her friend and the law partner, Swarns says, and, “I’m like, ‘This is what I do.’ ”

Her usually quick, high-pitched laugh grows to a cackle.

In another case, Swarns represented the headline-grabbing “serial diner” in 1994, a man who would eat in restaurants and leave without paying. He did so because he wanted to go to jail for regular, if not great, repast and a comfortable-enough place to sleep. The city and Rikers Island cooperated at least 31 times over the years.

After 2½ years at Legal Aid, Swarns moved to the position in the Philadelphia federal defender’s habeas unit in 1996, where she would stay for seven years before moving to the LDF in 2003.

With so much of her time consumed in talk and work concerning death, Swarns at one point took six months’ leave to concentrate on perhaps the most life-affirming possibility one can know.

In August 2008 she suddenly became a mother. The process took a full nine months, but the timing of an adoption is typically so uncertain that it often arrives like a lightning bolt, and this one did.

She had worked through a simple analysis: “I was sort of like, ‘Well, I’m not married and I want to have a family, so what are the options available to me?’ ”

International private adoption proved smoothest for a single parent. When the call came, Swarns’ parents accompanied her for a blur of a week in Ethiopia to pick up her 6-month-old daughter. Swarns had been able to specify only three things in her choice: girl, 8 months old or younger, no medical problems.

Now 4-year-old Amina’s artwork from preschool covers much of Swarns’ office door.

Swarns now sweats those other monstrous decisions: child care, preschool, kindergarten, gifted-talented, private or public, staying in Manhattan’s Washington Heights or jumping to New Jersey.

“Big decisions,” Swarns says. At least the grandparents are nearby on Staten Island, and Amina loves going there on the ferry every other weekend.

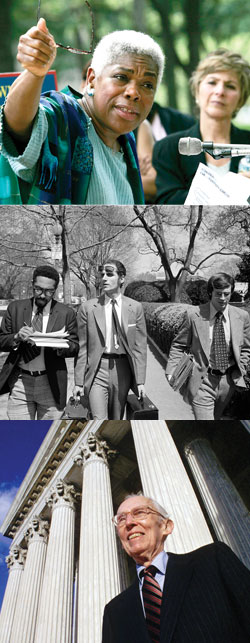

FELLOW DEFENDERS: Elaine Jones, the first woman to head the LDF, met Swarn’s inquiries as a 3L with an introduction to top LDF lawyers in the capital punishment project. Tony Amsterdam (2nd photo, center) outside the Supreme Court in 1975. Amsterdam, then a professor at Stanford, led the LDF’s efforts to eliminate the death penalty a decade earlier, which culminated in 1972’s Furman v. Georgia, which suspended its use. Former Justice Lewis Powell (bottom), who wrote the majority opinion in McCleskey v. Kemp, later said it was the one decision he most regretted and that he’d “come to think that capital punishment should be abolished.” Photos: Alex Wong/Getty Images, AP Photo/Charles Harrity, AP Photo/Richmond Times Dispatch, Stuart T. Wagner.

MAJOR CASE

With a splash last year, the LDF became active again in the 30-year-long case of Mumia Abu-Jamal, joining other lawyers still representing the most famous—or infamous—death row inmate in the world. Abu-Jamal, a radio journalist and black activist, had been sentenced to death in the 1981 slaying of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner.

Swarns had previously been co-counsel and argued (unsuccessfully) before the Philadelphia-based 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 2007 that prosecutors had improperly kept blacks off the jury.

The appeals court did, however, agree with a separate part of the challenge argued by longtime Abu-Jamal counsel Judith Ritter, a professor at Widener University School of Law in Wilmington, Del. Based on the Supreme Court’s 1988 decision in Mills v. Maryland, the court said Abu-Jamal’s original jurors had not been properly instructed and thus didn’t know that all 12 were not required to agree unanimously on mitigating factors in sentencing him for the murder. Just one could have held out and made it life without parole.

When the Supreme Court told the appeals court to reconsider its decision in light of a more recent case, the 3rd Circuit did so but declined to reverse itself.

Asked early last year to again join the case for the re-sentencing, Swarns cleared the decks for a staff that typically carries five or six death cases at a time. She began preparation for a new sentencing jury to be empaneled 29 years after Abu-Jamal was condemned to death.

They even planned a try at getting new, exculpatory testimony and evidence into the record, although guilt or innocence was no longer on the table, only death or life without possibility of parole. Abu-Jamal had become something of a rock star on the world stage, writing several books while caged in Pennsylvania, and the court battle likely would turn into a kind of Super Bowl of international criminal justice.

“It was going to be a dogfight,” Swarns says.

But after consulting with Faulkner’s long-suffering widow, Philadelphia District Attorney Seth Williams announced last December he would not pursue the matter further, letting Abu-Jamal move off death row and out of the worldwide spotlight.

The magnitude of Abu-Jamal’s case carried a whiff of the grand constitutional matters pushed by the LDF in earlier years, after Thurgood Marshall helped found the organization in 1940 and launched the series of court battles that culminated in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

But gone are the heady times in death penalty law when the LDF, led by the legendary Tony Amsterdam, set out in the early 1960s to put an end to capital punishment and succeeded, effectively so by 1967 and with certainty by a Supreme Court ruling in 1972.

The moratorium, however, was short-lived. While Furman v. Georgia in 1972 said states were arbitrary in applying the death penalty, four years later the high court decided in Gregg v. Georgia that the problem was cured.

There would be one more big-picture approach in the 1980s, when the LDF marched into the Supreme Court with exhaustive statistical evidence that, again in Georgia, African-Americans were far more likely than others to be sentenced to death, even more so when the victims were white. The court, ruling 5-4 in McCleskey v. Kemp in 1987, said an empirical data model could be a factor, but not the crux. The condemned man needed to show evidence that a specific person involved in his case engaged in racial discrimination.

McCleskey’s blow still stings the death penalty bar 25 years later. Members believe there is more and more evidence to bolster their argument that capital punishment is a continuation of Jim Crow law—that for the most part it’s about race.

“From the time your car is stopped, how you’re treated, how you’re tried in court, whether you get bail or not, sentencing—race affects all of those things,” argues Stephen Bright, president and senior counsel for the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, who has been involved in death penalty matters for more than three decades.

Thus there was little succor in an otherwise shocking revelation by Justice Lewis F. Powell when, asked by his biographer whether he’d like to change any of his judicial decisions, he said, “Yes, McCleskey v. Kemp.”

And there’s little salve for Swarns when she repeats part of a line from Justice William J. Brennan Jr.’s dissent, describing the majority’s concern that granting the relief would open a Pandora’s box. Brennan accused his colleagues of having “a fear of too much justice.”

“That ended all effective litigation of race in capital sentencing anywhere in the country,” says John Charles “Jack” Boger, who argued the case as then-director of the LDF’s capital punishment project. He now serves as dean of the University of North Carolina School of Law.

“McCleskey was in some sense the culminating case of that whole era of constitutional challenges to the death penalty,” Boger says. “The courts were more generally becoming skeptical of or hostile to constitutional claims. There was less and less appetite or zeal for finding constitutional violations, particularly in the death penalty area.”

Asked whether she looks at cases with an eye toward building a strategy for sweeping change by the high court, Swarns’ reply is quick and sharp: “No! This is not a Supreme Court I’d actively try to get involved with a race issue. We look for what we can have an impact with, and by and large that is not with the Supreme Court.”

NEW NAME, OLD FIGHT

INFAMOUS INMATE: Widener University’s Judith Ritter in 2010 after a hearing for client Mumia Abu-Jamal, convicted in 1982 of first-degree murder in the killing of a Philadelphia police officer. District Attorney Seth Williams, accompanied by the officer’s widow, announced in December that prosecutors would no longer pursue the death penalty against Abu-Jamal, whose plight has drawn supporters worldwide. Swarns welcomed the decision, noting that “we’re at a time when support of the death penalty is at an all-time low, and that reflects some of the concerns expressed by Mumia’s supporters.” Photos: AP Photo/Matt Rourke

The LDF’s long-running death penalty project was renamed the criminal justice practice in 1998, though it is also called the criminal justice project. The change broadened the organization’s approach to seeking an end to racial discrimination in the criminal justice system.

Part of the reason for retooling was the development of federal resource centers for post-conviction death penalty cases in about 20 states in the late 1980s and early 1990s. That picked up a lot of the LDF’s heavy load. (When Congress ended funding for those efforts in 1996 in a push to speed up executions, some continued as private nonprofits and have managed to remain a force.)

Under Swarns the LDF’s criminal justice practice has taken on other ways to battle discrimination in the justice system. When it was strictly the death penalty project, most other matters would be passed along to outside volunteer lawyers who were close to the organization.

Now, for example, there is pending litigation against New York City and its housing authority alleging police harass and discriminate against minorities with pedestrian checkpoints in certain housing projects. Residents, their families and friends complain that officers routinely ask for their IDs and charge with trespassing those who are unable to prove on the spot that they have reason to be there.

“People are arrested as they step outside their homes because they’re not carrying their papers,” Swarns says as her head tilts, eyes open wider and lips purse in a can-you-believe-that expression.

One of Swarns’ signature non-death-penalty projects at the LDF, the launch of a community organizing arm nearly three years ago, arose out of a capital case pending in Arkansas. It reflects a newer effort to burrow deeper in rooting out problems.

While preparing for a hearing in 2007 in Pine Bluff, Swarns was told by many there that the African-American community was oppressed and fearful when it came to the courthouse. The people perceived it as inhospitable and stayed away, meaning they tried to avoid jury duty.

“We struggled with how to anchor this in constitutional parlance,” says Swarns, “but in reality it is part of how this case came to be, with underrepresentation of blacks on jury pools as well as in terms of peremptory strikes. I said, ‘Let’s just present it, and we’ll figure it out.’ ”

Swarns put a local African-American lawyer, a former prosecutor, on the witness stand. He testified that at the time of the defendant’s trial, he believed that blacks were underrepresented on juries by design, through tactics such as race-based strikes by prosecutors, with one result being that they tried to skip out on jury duty when called.

When the hearing concluded, “several black court staffers and bailiffs swarmed our table,” Swarns says, “thanking us for actually bringing all that out in court.”

The witness, Gene McKissic, says he had raised the issues before but that a bigger, national voice made a difference.

“Because the NAACP Legal Defense team was raising it, and they were from outside the county, it had a much larger impact than when a lone defense attorney raises it in a single case,” McKissic says.

Still, Swarns says, “then we got on a plane to come back to New York and there was an unsatisfying feeling that we may win and help people on death row in Arkansas, but there’s something wrong if people are saying that today. I felt that our litigation shouldn’t be so isolated from what’s happening in real life.”

The LDF’s new community organizers have been working with the African-American community in Pine Bluff, holding meetings to discuss civic responsibilities and the need for blacks to participate, when possible, with the courts and the criminal justice system.

LEADER OF THE PACK

Swarns also has put her stamp on the LDF’s annual Capital Punishment Training Conference for death penalty lawyers, held at the historic Airlie Conference Center 50 miles southwest of Washington, D.C. The well-kept, bucolic Virginia retreat has space for only 200 conference-goers, and the event has become a prized invitation since its inception in 1979.

“It is the best single death penalty conference there is,” says Burr, who has been going since the beginning and was director of the LDF’s death penalty project from 1987 to ’94. He now is in Houston in private practice and consulting in federal death penalty habeas cases.

Burr was involved in vetting Swarns for the LDF position, has worked on cases with her and says he was taken aback by her strategic moves in court as well as her work on briefs. “I can’t believe how good she is for being as young as she is,” he says.

The Airlie conference is a mix of training, updates, networking and a dose of group therapy fit for Sisyphus. It has undergone significant change with Swarns running the show and handling the invitations. In a double scoop of irony, the LDF’s conference had been seen as lacking diversity.

“There’s diversity and then there’s diversity,” says Marc Bookman, a longtime conference attendee and now executive director of the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation in Philadelphia, after a lengthy career in the public defender’s homicide unit. “Sometimes it happens naturally and sometimes you have to promote people, keeping an eagle eye out for those ready to make big contributions in a leadership position maybe a little ahead of schedule,” he says. “Christina has done a great job at that.”

The conference has become noticeably younger and more racially diverse.

“I came in at a time when there was a generational shift in the community, with a lot more people involved,” Swarns says. “I invite those I see and interact with when I go to cities and conferences, and it reflects more of my perspective, age and experience.”

Swarns has been at the LDF for nine years, a long time in such emotion-draining work.

“It’s important that she’s stayed there,” says Bright. “Christina is building an institutional memory and a lot of relationships, which is immensely valuable to the organization.”

Now it seems the death penalty itself might be dying a slow death. Juries are informed about sentences for life without possibility of parole. They’re steeped in TV’s CSI craze for scientific evidence and sometimes expect the magic of science to solve any and all cases. Homicides are down and prosecutors are wary of prolonged cases. And the state putting someone to death is very expensive.

But Swarns doesn’t expect the uneven and unfair impact that race plays in the justice system to change in the foreseeable future.

“We will stay busy,” she says.