King Coal's Violent Reign: Century-Old Labor Strife Still Raises Constitutional Questions

Photo of Phil Fogleman by Rebecca Sell.

On May 8, in West Virginia’s primary election, President Barack Obama received nearly 60 percent of the 178,000 votes cast in the Democratic primary. His opponent, who received about 40 percent of the vote, was a convicted felon named Keith Judd who managed to get on the ballot despite the fact that he is serving a 17½-year prison sentence at the Federal Correctional Institution in Texarkana, Texas.

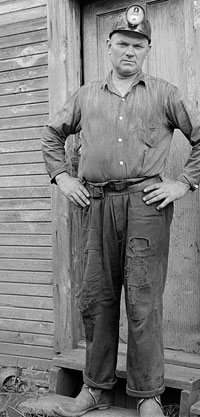

“Nobody had ever heard of this Judd, but they didn’t have to,” says Phil Fogleman, who sells modular and mobile homes to many of the miners who live in and around Summersville, a small community in the south-central part of the state. “It was strictly a vote against Obama. People are tired of the EPA restrictions on the coal industry. That’s our livelihood.”

In swing states like Ohio and Pennsylvania, coal is an issue. But in West Virginia, coal is—and always has been—the heart of every issue, whether taxes, elections, law enforcement, the environment or the courts.

A mine in Logan County, W. Va., is carved into mountaintops. The land is first cleared of trees and dynamited to get into the mountain, then soil is removed to allow machines to dig for coal. Photo by Rebecca Sell.

West Virginia is a land of deep-green mountains separated by fog-laden “hollers” and rippling creek bottoms. State tourism folks like to call it “wild and wonderful.” But much of its lush scenery sits atop broad seams of coal—coal that fueled eras of American industrial development, a way of life that now seems at risk. The outsourcing of those industrial jobs, competition with cleaner and cheaper sources of energy, and conflicts with environmental regulations have taken their toll on West Virginians who feel that they are simply holding on to everything they can.

Their immediate problem with Democrats was administration concern for mountaintop mining—the environmentally questionable practice of gouging mountain peaks with explosives to expose their rich veins of coal. In a rough-hewn state that has endured grinding poverty, high unemployment, mining disasters, labor violence and even martial law, the concern seemed to some misplaced. And across the state on billboards, on radio talk shows, in newspapers, in public forums and television advertising, West Virginians were urged to resist the Democrats and their “war on coal.”

What made the 2012 presidential election remarkable in West Virginia was more than concern for the coal industry; it was the extraordinary political partnership forged between two historic antagonists: coal miners and their management. It was an alliance that would have been impossible a century ago between the industry and the grandfathers of today’s mineworkers.

Miners light helmets to commemorate their 29 colleagues killed in an explosion in 2010. Photo courtesy of Steven Wayne Rotsch.

All but forgotten was the 2010 explosion that killed 29 miners at the Upper Big Branch mine in Raleigh County. A subsequent investigation revealed flagrant safety violations by the mine’s owner, Massey Energy. Forgotten, too, was a ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court just a year earlier that $3.5 million in campaign contributions by Massey’s CEO, Don Blankenship, may have influenced the appeal of a $50 million judgment against the company.

But also lost in the moment is the fierce, violent history of conflict between miners and management known to history as the West Virginia coal mine wars.

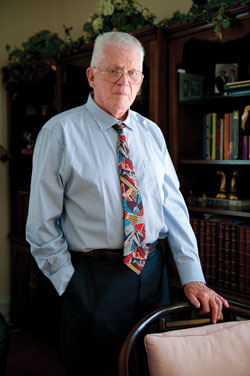

An early 20th-century West Virginia coal miner, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

STATE-SANCTIONED RESPONSES

Starting in the autumn of 1912, West Virginia coal miners waged one of the nation’s most significant labor strikes. In retaliating against the miners, the coal companies often were supported by the state government, which declared martial law three times and suspended many civil rights to suppress a labor strike.

In 1913, Socialist organizer John W. Brown closed a pamphlet titled Constitutional Government Overthrown in West Virginia with a demand for “the complete abolition of the nefarious guard system, the right to free speech and free assemblage on every inch of West Virginia soil, and the right of habeas corpus and trial by jury of every man accused of a crime, whether he be a citizen of West Virginia or otherwise.”

“Forget the feuding Hatfields and McCoys,” says historian Fred Barkey. “West Virginia was in the forefront of industry, and it was the jumping-off point for unionization.”

In the early 1900s, coal companies and wealthy out-of-staters owned nearly half of West Virginia. The New York Post reported in 1913 that “men of great capital have bought the oil, coal and timber lands and rule their domains like barons.” Those coal barons, as they came to be known, also owned the company towns, rented their tiny houses to miners, and evicted miners’ families if they were killed on the job, found employment elsewhere or refused to work.

Cora B. Older—whose husband, Fremont Older, served as managing editor for the San Francisco Bulletin—described arriving in West Virginia to cover the coal wars for the paper. “West Virginia was in a brown mood and a brown season,” she wrote in March 1913. “The trees were leafless, the mountains were brown, the sky was brown, the swift river along the edge of which the train reeled was brown, and the air was brown with dust.”

She described a West Virginia company town in her vivid description of a boy whose back had been broken in a mine accident: “Near the back of a river, at the base of scarred mountains, he lives. In order to reach his house, we wandered among unpainted and despairing shacks standing in typhoid cesspools; pigs and cows roamed through the muddy street; and dirty, barefoot children swarmed out of the doors.”

The companies often paid their workers in scrip redeemable only at their company stores. Prices were often two to three times higher than at stores in town. “Men could be paid in cash, but women were not allowed to use cash in a company store,” says Joy Lynn, co-owner of the Whipple Company Store & Appalachian Heritage Museum near Scarbro, a hamlet tucked in the hills between Charleston and the Virginia state line. “Since the men didn’t shop, they took scrip so their wives could shop. The philosophy was: Keep the women happy and the men will stay and mine coal. The companies also allowed women to buy goods on credit. That made them even more happy, and the men had to stay and mine more coal.”

A panoramic view of West Virginia’s capital city of Charleston taken in 1909, complete with brown haze as described by Cora Older for the San Francisco Bulletin. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Coal companies often retained public officials on their payrolls, particularly those in law enforcement who, in turn, would harass union organizers. Wrote social reformer Arthur Gleason in The Nation in 1913: “The operators pay directly to the sheriff $32,700 a year for this immunity from unionization. In addition, most of them pay the individual armed guard salary. These agents of the company are deputy sheriffs.”

“It is this exercise of public power under private pay which is one of the fundamental causes and is the most likely occasion of bad blood between owners and workers,” Gleason wrote.

Mine guards from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency were considered thugs with badges. Gianiana Seville described to a U.S. Senate committee the abuse she suffered at the hands of about 20 Baldwin-Felts guards. She said her baby was asleep on a bed when the guards entered her home during a house-to-house search of her Kanawha County neighborhood. When she objected, she said, “They struck me and I fell down, and then they kicked me in the stomach and they hit me with their fists in here (indicating) and then they knocked me down. … They asked me to give them the keys to the trunk and I refused to do it, and then they hit me and threw me down.” Mrs. Seville, pregnant at the time, wrote to her husband job-hunting in Ohio that she became so sick she thought she “might die.” She was taken to a hospital in nearby Hansford, where her baby was born dead.

One night in February 1913, Kanawha County Sheriff Bonner Hill commanded a train equipped with a Gatling gun that shot up a tent city occupied by striking Paint Creek miners and their families. Lee Calvin, a mine guard aboard the train which came to be known as the “Bull Moose Special,” later told a U.S. Senate committee that “they commenced streaming fire out of the baggage car—you know: flashes, reports and cracks from the machine gun at a lot of tents—and the train went along with a stream of fire which continued coming out of the Gatling gun all along, and in about 20 or 30 seconds there came a flash here and there from the tents.”

One miner was killed and a number of men, women and children were wounded. Calvin testified that Quinn Morton, a coal company operator aboard the train, “wanted to back the train up again until we could give them another round.”

Asked about the sheriff’s reaction, Calvin said, “I couldn’t hear what he said. The sheriff seemed to say there were women and children in the tents, and he would not do it.”

Photo of Mother Jones courtesy of Library of Congress.

ESCALATING UNREST

Violence had been building since the previous summer, when coal miners began striking at Paint Creek and Cabin Creek, just south of Charleston, demanding an end to mine guard brutality, the right to organize, the right to free speech and assembly, an end to the practice of blacklisting union organizers, and alternatives to company stores. They also demanded the installation and inspection of accurate scales at the mines. As the legendary union agitator Mary Harris “Mother” Jones—who had been involved with the United Mine Workers since the 1880s—told Mrs. Older: “The miners made so little they were always in debt to the ‘Pluck Me Store.’ They were docked so heavily that they never had necessities. They had to load 2,240 pounds for a ton instead of 2,000, as the union miners do.”

On Aug. 15, 1912, Jones stood on the steps of the state capitol to demand that Gov. William E. Glasscock outlaw the Baldwin-Felts mine guards, whom she termed “bloodhounds.” “If the governor won’t make them go, then we will make them go,” Jones told thousands of cheering miners. “I want to tell you that the governor will get until tomorrow night, Friday night, to get rid of his bloodhounds. And if they are not gone, then we will get rid of them.”

But Glasscock, though an advocate of mine safety and environmental protection laws, had other ideas. On Sept. 2, he imposed martial law, sending in 1,200 members of the state militia to disarm the miners. Soldiers seized 1,872 rifles, 556 pistols, six machine guns, 225,000 rounds of ammunition and 480 blackjacks, according to Howard Lee, who was state attorney general at the time. “In the history of the United States, martial law has never been used on such a broad scale in so drastic a manner, nor upon such sweeping principles as in West Virginia in 1912-1913 during the Paint Creek trouble,” wrote constitutional historian Robert Rankin in 1939. “Here is the climax of the use by the state of its power to declare and to carry into effect martial law with all its force.”

At least 200 striking miners and their leaders were arrested without warrants and detained in makeshift jails. More than 100 civilian miners were then court-martialed in military tribunals and sent to prison.

In Life, Work and Rebellion in the Coal Fields, David Alan Corbin wrote: “There was no pretense of balanced justice in this unconstitutional proceeding—the coal operator and Baldwin-Felts guards who were on the Bull Moose Special were never even questioned, while a striking miner was sentenced to five years in prison for telling an Army officer to ‘go to hell.’ With true military efficiency, the miner was arrested on Tuesday, court-martialed on Wednesday and was in prison on Thursday.”

Even Mother Jones, by then 80 years old, was tried by a military court on a number of charges, including conspiracy to commit murder. Though sentenced to 20 years in prison, she refused to recognize the court’s legitimacy. She was released after 85 days to a boarding house that had been designated to hold prisoners.

Photo of Gov. William Glasscock courtesy of Library of Congress.

CONSTITUTIONAL CONFLICT

As Jones suspected, Gov. Glasscock was on shaky legal ground. While he had statutory authority to call out the National Guard to quell what he termed an insurrection, the state constitution at that time required that its civil rights protections remain intact in times of war. Echoing Ex parte Milligan, a unanimous 1866 Supreme Court decision regarding Civil War-era suspensions of habeas corpus, the state constitution carried an expressed prohibition against civilians being court-martialed: “No citizen, unless engaged in the military service of the state, shall be tried or punished by any military court for any offense that is cognizable by the civil courts of this state.” In Moyer v. Peabody, a 1909 Supreme Court decision that grew out of miner unrest in Colorado, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes had given governors broad authority: “So long as such arrests are made in good faith and in honest belief that they are needed in order to head the insurrection off, the governor is the final judge and cannot be subjected to an action after he is out of office on the ground that he had not reasonable ground for his belief.”

So attorneys for the striking miners challenged the governor’s use of martial law three times, and three times a majority of the West Virginia Supreme Court upheld his decree.

On March 4, 1913, Dr. Henry D. Hatfield—elected to replace Glasscock as governor (a state law limited governors to serve only one term)—delivered his inaugural address. The Argus, a socialist-leaning newspaper in Huntington, paid its final tribute to an old adversary: “To mention the word justice in the same column with the name Glasscock is a crime, and the mere suggestion of a man appointing a court to try citizens of West Virginia without a jury or any other of their constitutional guarantees is a damnable outrageous insult that our hardy forefathers would have wiped out with the blood of its author.”

Hatfield was a nephew of William “Devil Anse” Hatfield, one of the principals in the legendary family feud with the McCoys along the West Virginia-Kentucky border. Still, he brought a peacemaker’s instincts to the office. “I quietly turned out of jail and the penitentiary all military prisoners who had been sentenced by my predecessor,” wrote Hatfield, a progressive Republican who supported labor unions and workers’ rights.

Hatfield decided that only a bold stroke could end the civil unrest, so he imposed his own settlement on both sides, demanding that the miners end their strike within 36 hours or face deportation from West Virginia. In return, the miners were allowed to unionize, granted a nine-hour workday, permitted to trade in independent stores, and given a slight increase in coal tonnage rates. It’s unclear how Hatfield intended to enforce this dubious edict, but the governor sent state troopers into the mining camps to “encourage” the miners to return to work. In the end, the miners decided not to call Hatfield’s bluff.

What came to be known as the Hatfield contract squelched the strike, but the peace that settled in at the mines was very uneasy.

Photo of Gov. Henry Hatfield courtesy of Library of Congress.

While the governor supported the miners’ right to shop in independent stores, for instance, there were few ways to enforce it. Lynn says the Whipple Company Store continued to issue its own scrip until it closed in the mid-1950s.

“I recall as a kid that there was a theater in Cedar Grove that would take scrip, but scrip was pretty much gone by the 1940s,” says Patrick Maroney, a West Virginia native who is general counsel to the state AFL-CIO. “We had two company stores in my town and there were a couple more up Cabin Creek. About every town had one. Miners would have to deal with the company stores, and by the time they had taken out the rent, the food and the electricity, there generally was little left.”

Another nagging problem in the coalfields was the continuing presence of law enforcement officers and members of Baldwin-Felts and other private agencies on the payroll of the mine companies.

The West Virginia legislature moved to close the loophole that allowed coal companies to subsidize county sheriffs to help keep their workers in line. A statutory provision states: “A sheriff in any county in which there are more than four deputies shall devote his full time to the performance of the services or duties required by law of such sheriff, and he shall not receive any compensation or reimbursement, directly or indirectly, from any person, firm or corporation for the performance of any private or public services or duties.”

Moreover, Hatfield’s pardons may have kept the issue of military courts-martial of civilians from getting to the U.S. Supreme Court. It wasn’t until 1946, in Duncan v. Kahanamoku, that the Supreme Court affirmed Ex parte Milligan by ruling that a military tribunal in Hawaii had no authority to convict and imprison civilians.

By squelching press opposition to his settlement of the coal wars, Hatfield was also treading on thin First Amendment ice. When two socialist-leaning newspapers, including the Argus, prepared to attack Gov. Hatfield’s settlement as a sellout, the governor ordered them shut down. On April 29, 1913, military authorities seized the Argus and arrested its editors. State officials then shut down the Huntington Socialist and Labor Star, confiscating a printing plant and arresting five people.

The small town of Matewan has been the subject of many a coal mining dispute—as well as a major motion picture. Photo by Rebecca Sell.

SOVEREIGN IMMUNITY

The Socialist Printing Co. of Huntington sued Hatfield and four National Guard officers for trespass and for conspiring to destroy a printing office and suppress their paper. But a majority of the state supreme court ruled that the governor’s actions and warrants were not subject to judicial review, that the governor could not be held liable for damage to private property when carrying out his duty, and that the governor had the power to arrest and detain disturbers of the peace and temporarily suppress the publication of any newspaper.

It’s not clear why the newspapers never carried their appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, but Corbin suspects it may have been due to lack of money. “The presses were always small circulation, and after being smashed by the governor and their editors incarcerated, both were simply trying to stay afloat,” he said in an email interview.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, many of the miners joined the military. They returned from Europe a year later to find the coal wars had flared up once more, due largely to the continued aggravation of the mine guards. Coal companies, fully flush with wartime profits, seemed determined to claw back union gains. Most refused to allow an independent check of their scales and they returned to former hostilities: discharging, evicting and blacklisting union miners and breaking up union meetings in private homes. It seemed to the miners that they were being denied the very freedoms they had gone to war to protect. A new coal strike broke out around Logan, about 60 miles southwest of Charleston. On May 19, 1920, Baldwin-Felts armed guards came to the small town of Matewan, close to the Kentucky state line, to evict the families of striking miners from their homes. Matewan Chief of Police Sid Hatfield—a member of the sprawling Hatfield clan who had grown up in the backwaters of the Ohio River along the Kentucky border—and Mayor Cable Testerman intervened. A gunfight broke out in which the mayor, two miners and seven mine guards were killed.

Hatfield was tried for murder and acquitted by a local jury for lack of evidence. But Hatfield and co-defendant Ed Chambers, son of a Matewan hardware store owner, were later gunned down in August 1921 on the courthouse steps of nearby Welch. That sparked outrage across the state, and between 10,000 and 20,000 miners began marching on Logan County to drive out the Baldwin-Felts private detectives.

Both sides met at the Battle of Blair Mountain, where thousands of shots were fired. The miners were bombed by the “Logan air force,” three little biplanes under the direction of Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin (who was receiving the aforementioned $32,700 annually from the coal industry to keep order); and 15 to 20 men were killed.

Gov. Ephraim F. Morgan issued a proclamation demanding an end to the fighting within 48 hours. When that didn’t work, he termed the battle an insurrection and asked President Warren G. Harding to place the state under federal martial law. Harding sent in 2,500 federal troops from Kentucky, Ohio and New Jersey. He also ordered in a squadron of planes equipped with gas bombs and machine guns, but these were never used.

The miners, reluctant to take on federal troops, finally dispersed and went home. In the years that followed, there was a fair amount of violence, according to Barkey, but it was generally sporadic and in response to provocations.

Fred Barkey: “When Hatfield began pardoning the imprisoned strikers, he didn’t pardon everyone at once. He left the radicals to languish in prison for a few years.” Photo by Rebecca Sell.

UNION VALIDATION

One of the major impacts of the 1912-13 coal mine wars was the right to unionize, which was also a part of the Hatfield settlement.

“Hatfield went to the mine operators and told them he could use the military to ensure that they had good labor relations, but that they would have to deal responsibly with labor unions. Then when Hatfield began pardoning the imprisoned strikers, he didn’t pardon everyone at once. He left the radicals to languish in prison for a few years,” says Barkey, a retired history professor who has specialized in the coal wars.

“The coal mine strikes kept the union movement alive in West Virginia,” Maroney says. “They were a big force behind the UMWA, and that culminated in the National Labor Relations Act of 1936. I think that was one of the big embers in that bonfire.”

With relative peace in the coalfields, West Virginia developed a rural industrialization, with aluminum and steel mills for the auto industry, chemical plants up and down the Kanawha River, tanneries and shoe factories, logging and furniture firms, and clothing mills.

“Unionization peaked a couple of decades ago,” says Maroney, the AFL-CIO’s general counsel. “The movement is strong, but the member base in the U.S. has declined due to the loss of jobs to overseas.”

Over the past half-century, many of West Virginia’s young people left the state looking for work. Between 1950 and 1970, West Virginia lost a staggering 260,000 people—13 percent of its population. Today, the state’s workforce 16 to 45 years old is only 85 percent as large as that of the baby boomers, 45 to 64; by comparison in the rest of the country, pre-boomers slightly outnumber the boomers.

The United Mine Workers of America was a huge force in West Virginia, the largest coal-producing state in America until it was overtaken by Wyoming with its thick beds of low-sulfur coal, which more easily met ever-increasing environmental regulations. In addition, mechanization involved in strip mining and mountaintop removal cut the need for workers. The 1960 census put mining in a category of its own: There were 59,100 miners in the state, making up 11 percent of the population half a century ago. By 2011, however, mining was lumped in with agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting; the combined total was 40,115, which is only 5.4 percent of the workforce.

Trucks are lined up and ready at a coal mine in Mingo County, West Virginia. Photo by Rebecca Sell.

BIG COAL DOMINATES

As late as 1994, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration records, more than half of West Virginia’s 22,000 miners belonged to the UMWA. By 2010, the number had dropped to 20,953, but only 5,952 (about 28 percent) belonged to the union. “Nonunion mines pay the same wages or better than union mines,” explains Fogleman, the modular-home salesman, adding that he knows miners with high school diplomas making as much as $125,000 a year—while kids with college degrees can’t find jobs in West Virginia.

In addition to making Western coal more attractive, the increasing EPA regulations drove up operating costs, forcing most of the ma-and-pa coal companies out of business, says Barkey. Diminished competition gave the big coal companies more revenue to spend more creatively.

In 2004, Blankenship, then CEO of coal giant A.T. Massey, spent close to $3.5 million on a statewide ad campaign to elect a state supreme court justice who proved to be the swing vote in overturning a $50 million judgment against his company.

In 2006, Blankenship took electioneering to a new level with a personal campaign—estimated to cost more than $6 million—to run many Democrats out of the state legislature. It backfired and Democrats gained six seats, says Derek Scarbro, executive director of the Democratic Party of West Virginia.

At the same time Blankenship was seeking to win political power, he sent out a hugely controversial memo to all deep-mine superintendents that placed coal production above everything else, presumably including mine safety. It said: “If any of you have been asked by your group presidents, your supervisors, engineers or anyone else, to do anything rather than run coal (i.e., build overcasts, do construction jobs or whatever) ignore them and run coal. This memo is necessary only because we seem not to understand that coal pays the bills.”

Two years ago, methane exploded in the Upper Big Branch Mine owned by Massey Energy and killed 29 of 31 miners. The Mine Safety and Health Administration investigated and concluded that “Massey, through its subsidiary Performance Coal Company, violated numerous, widely recognized safety standards and failed to prevent or correct numerous hazards that ultimately caused this catastrophic explosion.

“The operator concealed its highly noncompliant conduct in a number of significant ways.

“The operator provided advance notice of MSHA inspections, allowing foremen to correct violations before inspectors arrived underground to detect them. It concealed several occupational injuries by failing to report them to MSHA as required.

“The operator recorded hazards in internal production reports rather than in the examination books required by MSHA standards.

“Finally, it intimidated miners into not reporting hazards to MSHA, compromising miners’ ability to participate in the identification and correction of hazards.”

That investigation led U.S. Rep. George Miller of California, the senior Democrat on the House Education and Workforce Committee, to condemn everything from “the agency’s failures to fully enforce the Mine Act, to the inherent weaknesses in that law, to a company hell-bent on exploiting those weaknesses.”

Phil Fogleman has been selling modular and mobile homes as an affordable living option in coal country for almost 40 years. Photo by Rebecca Sell.

With huge liabilities clouding its future, Massey was sold to Alpha Natural Resources. As part of that contract, Alpha agreed to provide $190 million in severance payments to a select group of company executives. Blankenship alone was promised more than $86 million.

Alpha also paid $200 million to the federal government to settle an investigation by the U.S. attorney’s office into Massey’s mine safety practices. It offered wrongful-death settlements of $3 million per victim, on top of health benefits and college tuition, and it reached a confidential settlement with families of all the dead miners, although some of the early settlers have since filed suit to back out of their agreements, claiming they had been unaware of the magnitude of the mine’s safety violations.

And then, just six weeks before the general election, Alpha announced it was cutting production by 16 million tons and would close eight mines in West Virginia, Virginia and Pennsylvania. About 10 percent of its 13,000-person workforce would be laid off, according to Alpha.

That’s painful news in a state where 335,000 residents—18.6 percent—are already below the poverty level and where 122,300 families—16.6 percent—are receiving public assistance or food stamps.

“My wife works for a trucking company that hauls coal, and they just laid off 125 people,” Fogleman says. “Half of their trucks are sitting idle. My business is about 35 percent of what it was when Obama took office, and my employment is down 50 percent. Coal is a huge force in this state.”

Sidebar

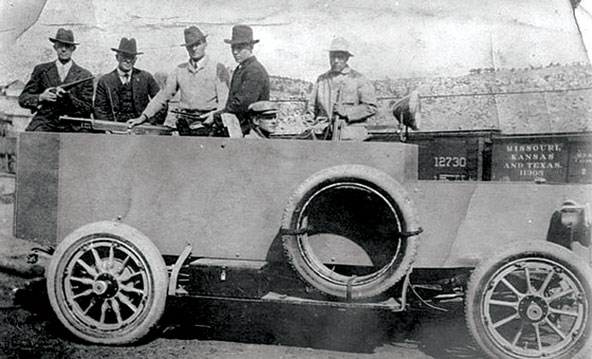

Baldwin-Felts detectives in the “Death Special.” Photo courtesy of Colorado Historical Society.

State Courts & Strikes

Like a storm system spinning off tornadoes, America’s labor movement has spawned violent confrontations over this past century. Martial law has been invoked on a number of occasions, but guidance from the U.S. Supreme Court as to what state authorities could do—or not do—is sparse.

The West Virginia coal mine wars were followed by similar miners’ strikes in the West. In the fall of 1913, Colorado Gov. Elias Ammons ordered the National Guard into the coalfields to preserve peace, but on April 20, 1914, troops fired on a striking miners’ colony at Ludlow, reportedly killing 20 inhabitants, among whom were thought to be seven miners, two women and 11 children. President Woodrow Wilson ordered federal troops into the Colorado coalfields to restore order. And on June 23, 1914, the Miners Union Hall in Butte, Mont., was dynamited, leading to seven years of martial law. In 1920, mine guards fired on striking miners, killing two and wounding another dozen, and again federal troops were called in to restore order.

Both governors acted in accordance with a 1909 Supreme Court decision, Moyer v. Peabody, which gave them broad authority to suppress insurrection. It wasn’t until 1932 that the court restored some balance. In Sterling v. Constantin, it ruled that Texas Gov. Ross Sterling overreacted by imposing martial law to correct an overproduction of oil during a period of low oil prices, making declarations subject to judicial review. “What are the allowable limits of military discretion, and whether or not they have been overstepped in a particular case, are judicial questions,” wrote Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes.

Rare Supreme Foray

It was one of the few times the nation’s high court has addressed the subject of martial law, according to Vermont Law School professor Steve Dycus, an expert on national security law. “This is an extremely important and under-recognized issue,” he told the ABA Journal. “Martial law is the first thing that we need to avoid in planning for our next crisis.” But the labor confrontations continued unabated after the three mine wars.

Steve Dycus: “Martial law is the first thing that we need to avoid in planning for our next crisis.” Photo courtesy of University of Vermont Law School.

Throughout the 1920s, there were hundreds of strikes in textile mills in the Southeast, culminating in a national strike in 1934 in which 400,000 workers walked off the job. The National Guard was called out in Connecticut, Georgia, Maine, North Carolina, Rhode Island and South Carolina. In Georgia, about 100 picketers were held in a former World War I prisoner-of-war camp for trial by a military court. Ultimately, President Franklin Roosevelt intervened by urging employees to return to work and employers to accept the recommendations of the newly created National Labor Relations Board.

In 1955, a dispute between management of the Perfect Circle foundry in New Castle, Ind., and the United Auto Workers resulted in violence, and the National Guard was ordered in by the governor, who declared the county a military district under military rule. Troops set up roadblocks around the city, searched automobiles, and seized firearms and liquor. Several bootleggers and curfew violators were arrested.

An article in the 1956 Indiana Law Journal summed it up this way: “Under normal conditions the action taken by the military in Henry County would not have been tolerated. Individual rights secured by both state and federal constitutions were invaded. The right to bear arms, ‘to peacefully assemble,’ to be secure against unreasonable search and seizures were restricted by the military. Merchants properly authorized by statute and license to sell liquor or firearms were forbidden to do business. The statutory right of properly licensed persons to carry concealed weapons was denied. Orderly civil process was supplanted by military government.”

Dycus, quoting 18th century English jurist William Blackstone as saying that martial law is really no law at all, says the courts have historically backed away from challenging a chief executive’s handling of emergency situations. “That means that we can only rely on the good intentions of the person invoking martial law to restore order.” - E. N.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Eric Newhouse is the author of Faces of Combat: PTSD & TBI. He also blogs on the mental health issues of veterans for Psychology Today.