Killing Your Case with Clutter

Illustration by John Schmelzer

On Wednesday afternoon, Angus and I went to Federal District Judge Garcia’s courtroom to hear the opening statements in Boxwell Industries v. Caretex Containers, a $250 million commercial fraud case. Ernie Romero, who specializes in commercial litigation, had asked Angus to evaluate his opening for the plaintiff and tell him how well it set the tone for the trial.

Because of the size of the case, Judge Garcia granted Ernie’s request for extra time for the opening statements, giving each side 45 minutes instead of holding them to his usual 30-minute limit.

Ernie’s opening followed a strict chronological order that kept him hopping back and forth from one topic to another. He did it in such meticulous detail that it took 12 different charts set up on wooden easels around the courtroom to cover everything he said.

Ernie kept talking as he walked from one easel to the next and pointed out where he was on each outline. It was more than a little disconcerting.

While all this was going on, one of the associates from Ernie’s firm leaned over and whispered, “I’ve never seen anything like this before. I guess this is what people mean by a tour de force. Anyway, Ernie doesn’t need these outlines. You can tell by his pace that he’s got it all memorized. He’s doing it this way because he read somewhere that people are more likely to believe something if they see and hear it at the same time.”

I didn’t answer him because I was concentrating on how Ernie was coming across to the judge and jury. It bothered me that he kept the same clipped pace going the entire time. By the time he hit the 30-minute mark, everyone in the courtroom was looking more than a little dazed.

As Ernie got close to 40 minutes, Judge Garcia was holding his gavel in his hand and staring at the clock on the wall. When Ernie was almost out of time his pocket watch gave three little beeps. He stopped, turned off the beeper and said, “Your honor, ladies and gentlemen of the jury, that will be the plaintiff’s case. Thank you for your time and attention.” He took his seat with 15 seconds to spare.

Then Sarah Oldham, the corporate defense lawyer who was representing Caretex, asked Judge Garcia if we all might have a 15-minute recess, which he happily granted. I noticed that all the jurors looked grateful and smiled at Sarah as they filed out of the room.

When court was back in session, it was Sarah’s turn to smile at the jury. Then she said, “I promise I will be mercifully brief. I’m not even going to try to touch on all the points that Mr. Romero talked about. I just want to tell you that Mr. Romero will not be able to keep his promise and prove his case.

“That’s because there are three essential facts that the law requires from the plaintiff—Boxwell Industries—in a case like this. It has to prove that Caretex Containers—the good folks on the other side of this case—did three things that they could not, would not and did not do. Here they are. … ”

What Sarah Oldham said was clear, simple and impressive. And it took less than seven minutes from start to finish.

JURY? WHAT JURY?

After the opening statements were finished and the defendant’s motion to dismiss was denied, Judge Garcia announced that testimony would begin the next morning at 9 o’clock.

When Ernie showed up at our office at 7 that evening, he was still on an intense high that had driven him all through that long opening statement.

“How do you feel your opening went?” said Angus.

“I was pumped,” said Ernie.

“So let me ask you another question,” said Angus. “How do you think the jury liked it?”

“You know,” said Ernie, “I was so busy with covering all the things I had to say and pointing out all the details in my flow charts and exhibits, I didn’t have time for much eye contact with the jury. Why? Do you feel eye contact is particularly important?”

“Yes,” said Angus. “Among other things. You talked for almost exactly 45 minutes. But in all that time you weren’t talking with them or to them, but at them. Which means I don’t think you were getting through to them.”

“I don’t know if I follow you,” said Ernie.

THE MORAL IMPERATIVE

Angus smiled. “Ernie,” he said, “you’re a bright lawyer. In many respects, the opening statement you gave was brilliant. But there were only two or three jurors who were with you even part of the time. I know because I was watching them.

“And if you had been watching the jury, you would have spotted them, too. Not only that, but watching the whole panel would have started shaping what you said and how you said it so as to draw all of them into the moral imperative of your case.”

“The moral imperative?” said Ernie. “What are you talking about?”

“The moral imperative for the plaintiff in any case,” said Angus, “is the wrong that needs to be set right by the judge and the jury.”

“And for the defendant?” said Ernie.

“The moral imperative for the defendant,” said Angus, “is that it would be unfair—an injustice—to answer for a wrong that was not done at all—or at least was not done by the defendant.

“The moral imperative is what should shape what you do in every case you try and how you try it. Of course you have to satisfy the technicalities of the law to get into court and stay there. But it is the moral imperative—the sense of an injustice—that makes judges and juries actually want you to win when you’re the plaintiff, or not pay for what you didn’t do when you’re the defendant.

“It’s that basic.”

“And that’s what has the power to shape how people relate to your case?” said Ernie.

“Exactly,” said Angus. “But no matter how powerful the moral imperative, there are a lot of destructive forces that can kill your case.”

“Like what?” said Ernie.

“Like what lots of lawyers do every day,” said Angus. “Kill their cases with clutter. Not all facts have the same value. Just because something is relevant and admissible in evidence doesn’t mean you have to mention it in your opening statement.”

ONE LUMP OR TWO?

“I think I know what you did,” said Angus. “You followed a strict time line in your opening statement, which made you hop from one point to another and then back again instead of putting the whole case together as one coherent story.

“You’ve got to understand that stories are the key to the successful trial of every case.

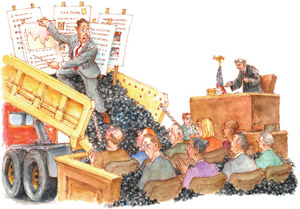

“Everything you said in your opening statement was relevant and admissible. But throughout your opening, I had this strange feeling that I was trapped in a huge coal bin that was being slowly filled with an entire truckload of coal. It was all good coal, but I couldn’t tell one lump from another or how those lumps fit together to tell the story of the case—which is, after all, what your job is in every opening statement.

“One last point,” said Angus. “And it’s an important one.”

“Should I take notes?” said Ernie.

“No,” said Angus. “I think you’ll remember. Stop talking like a lawyer. Remember, legalese is a powerful part of the destructive force of clutter.”

Jim McElhaney is the Baker and Hostetler Distinguished Scholar in Trial Practice at Case Western Reserve University School of Law in Cleveland and the Joseph C. Hutcheson Distinguished Lecturer in Trial Advocacy at South Texas College of Law in Houston.