Precedents

June 3, 1918: Child labor law declared unconstitutional

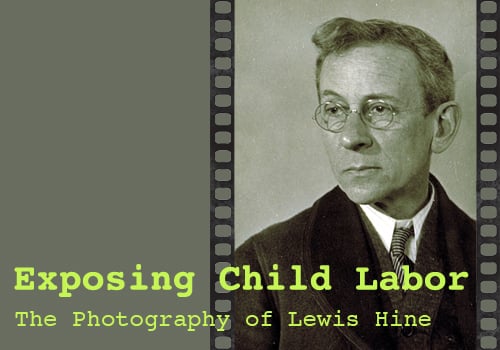

Photo by Lewis Hine and courtesy of the Library of Congress

Within the communities where child labor flourished, the practice was slow to be considered a social evil. Family farms had long been built on what was essentially child labor, and cultural acceptance of the working child lingered as farms made way for factories. Public response to the realities Hine revealed was electric. Riding a wave of increased pressure from Progressives, a bipartisan Congress passed the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act of 1916, banning the interstate sale of any products produced with child labor that did not meet fundamental federal standards: no employment of any child under age 14 and eight-hour workdays for children 14 to 16.

Having foreseen the futility of stopping the legislation in Congress, a group of Southern textile manufacturers decided to turn to the courts. Prompted by David Clark, publisher of the Southern Textile Bulletin, the Executive Committee of Southern Cotton Manufacturers recruited as its plaintiff Roland Dagenhart, an employee of the Fidelity Manufacturing Co. in Charlotte. With his legal expenses paid by the committee, Dagenhart challenged the new law, arguing that the federal restrictions effectively deprived him of income generated by his two sons, Reuben and John, who worked with him at Fidelity. Reuben, 14, faced cuts in his 60-hour workweek. John, 12, would be forced to stop working altogether.

But in carefully choreographed litigation, Dagenhart's personal complaint yielded quickly to a broader attack on the law's dependence on congressional powers over interstate commerce. Clark's group argued that congressional interstate authority was designed to thwart harmful activities—to the extent they depended on interstate transportation. Manufacturing goods, they asserted, didn't involve commerce.

In a 5-4 decision in Hammer v. Dagenhart, Justice William R. Day echoed the industry argument. Congressional power to regulate interstate commerce was intended to stop interstate trafficking of prostitution, kidnapping, fraudulent lotteries, bootlegging and the like, he wrote.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes was flabbergasted at the logic. To implicitly endorse Prohibition as being within congressional power—but not the regulation of child labor—seemed to him inconsistent, to say the least: "If there is any matter upon which civilized countries have agreed—far more unanimously than they have with regard to intoxicants and some other matters over which this country is now emotionally aroused—it is the evil of premature and excessive child labor."

Years later, Reuben Dagenhart reflected bitterly on the lawsuit. Facing adulthood drastically undersized and undereducated, he believed that child labor had ruined him as an adult: "It would have been a good thing for all the kids in this state if that law they passed had been kept."