June 3, 1943: The zoot suit riots begin

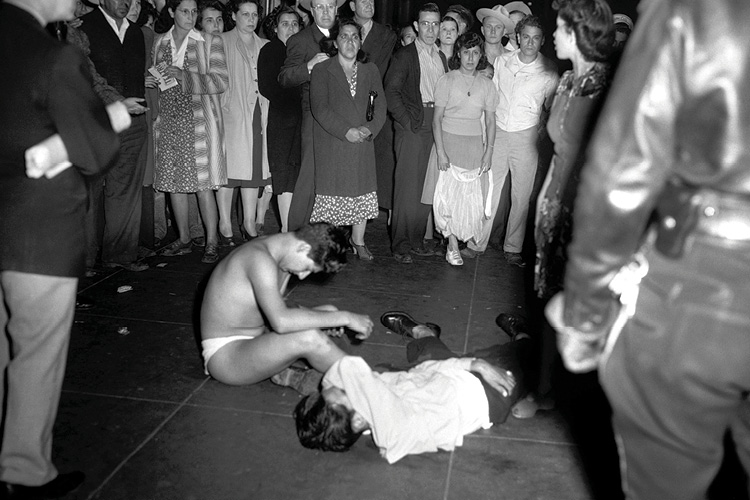

Victims of the zoot suit riots. AP photo by Harold P. Matosian.

On June 3, 1943, an estimated 50 sailors stationed in Los Angeles crammed into taxis and swarmed into the nearby Alpine Street neighborhood of East LA, where they began beating a group of teens, several dressed in zoot suits—the loose-fitting bib and tucker associated in the local press with Mexican American youth gangs.

Angered by reports of sailor Joe Dacy Coleman being beaten by “zooters” a few nights before, the mob fanned out. The sailors stormed into the nearby Carmen Theater, combing the crowd for pachucos—young Latinos with ducktail haircuts, long watch chains or blousy shirts associated with zoot-suit style. They stripped them of their clothing, beat them and moved on to other neighborhoods before returning to the Naval and Marine Corps Reserve Center in Chavez Ravine.

Over the next five days, the violence continued unabated each night as hundreds of sailors and Marines joined in droves. They roamed the streets, bars and theaters of East LA with makeshift weapons, seeking to confront nonwhite youths they regarded as draft dodgers—though victims were as young as 12—and petty criminals. Cabbies offered free rides to riot areas. Police followed in squad cars, watched the beatings, then arrested the victims.

The violence finally subsided after June 8, when military authorities made greater Los Angeles off-limits to its personnel.

Even before the Coleman incident, race relations in LA had been uneasy between the city’s Mexican residents and sailors and police. Depression-era “repatriation” laws had allowed mass deportations enforced by street-level harassment and military-style raids on whole neighborhoods. As a result, thousands of Mexican families suffered deportation, including thousands of individuals who were U.S.-born.

‘Sleepy Lagoon’ murder

By 1942, deportations had subsided, but they were replaced in some quarters with concerns over “juvenile delinquents” in the form of zoot-suited youths. Local press coverage stoked the hostilities with race-baiting tales of petty crime and gang violence epitomized by the “Sleepy Lagoon” murder and one of the largest criminal trials in California history.

On Aug. 2, 1942, Jose Diaz, a 22-year-old farmworker who had recently enlisted in the Army, was found unconscious near a reservoir local youths knew as Sleepy Lagoon. Diaz was taken to a local hospital where he died hours later, having suffered a fractured skull.

By all reports, Diaz had been swept up in a melee earlier that night involving zoot-suited teens at a nearby birthday party. Police and sheriff’s deputies made a massive sweep of Mexican neighborhoods, rounding up an estimated 600 young Mexican Americans for questioning. Ultimately, 22 were charged with murder in connection with Diaz’s death and assault with the intent to murder two other young men.

In a 13-week trial before Judge Charles Fricke, barely two months after Diaz’s death, 12 were convicted of murder and five of assault. Five were acquitted.

Less than two years later—citing a lack of specific evidence against the defendants—the murder convictions were reversed by a unanimous California appeals court.

In addition, the court questioned the trial management of Judge Fricke. The judge routinely interfered with defense cross-examination, disallowing testimony that some witnesses were beaten or intimidated by police. From the time of their arrest months before, the defendants were refused haircuts and changes of clothes, forcing them to appear before the jury as “mobsters,” as one of their lawyers complained. Moreover, all 22 defendants were confined to a space far removed from their various attorneys, rendering them unable to assist in their own defense.

Ignored on appeal, however, was the expert testimony of Ed Duran Ayres, head of the sheriff’s foreign relations department. In a written report and subsequent testimony that allowed a wartime conflation of the defendants and the Japanese enemy, Ayres opined that Mexican youths—as heirs to the Aztecs—were biologically prone to violence and, as “evidently Oriental,” held “utter disregard for the value of human life.”

The appeals court assured that—because the victims themselves were Hispanic—the trial, though flawed in its justice, bore no evidence of racial discrimination.