On the Thursday in July 2020 that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil M. Gorsuch read the majority opinion in McGirt v. Oklahoma, Assistant U.S. Attorney Shannon Cozzoni sprang into action. In that moment, she knew what would happen next: Scores of major crime cases would be landing in her federal court district in Tulsa, requiring rapid adjustments and recalibration.

“I thought, ‘We have to start filing cases,’” says Cozzoni, who serves as deputy criminal chief and tribal liaison for the Northern District of Oklahoma. “I immediately went down to the former U.S. attorney’s office, and we sat down and started coming up with a plan on intake and how to start getting” cases.

Although Cozzoni’s office had not been part of the litigation, the McGirt decision was poised to upend future operations of the Tulsa-based federal court. McGirt involved a criminal defendant, Jimcy McGirt, who challenged his 1997 sex crimes conviction by the state of Oklahoma on the grounds that he is a member of a Native American tribe and the crime occurred on tribal lands, known in federal statutory language as “Indian Country.”

The U.S. Supreme Court reversed his conviction. The 5-4 decision written by Gorsuch and joined by Justices Stephen G. Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan and Sonia M. Sotomayor held that the state of Oklahoma had improperly exercised criminal jurisdiction over McGirt on Muscogee (Creek) Nation land, and that criminal jurisdiction had been wrongly claimed by the state for 113 years—since Oklahoma became a state in 1907.

"We just have to work together. It's a new scenario. The crimes are not new. But it is a new way of dealing with them." –Shannon Cozzoni

“On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise,” begins Gorsuch’s 42-page opinion, referring to the forced 1830s removal of Indigenous people to territory west of the Mississippi River and the treaties that declared that the Creek nation would be self-governing.

“Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word,” the majority said, noting Congress never “disestablished” the reservation territory, so it still exists as established.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., in dissent, was joined by Justices Samuel A. Alito and Brett M. Kavanaugh, while Justice Clarence Thomas joined in part, arguing that contextual evidence supported the view that the reservation had been disestablished and no longer existed, and that reliance and practical considerations weighed against holding otherwise.

Justice Gorsuch addressed this preemptively: “Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law,” he wrote.

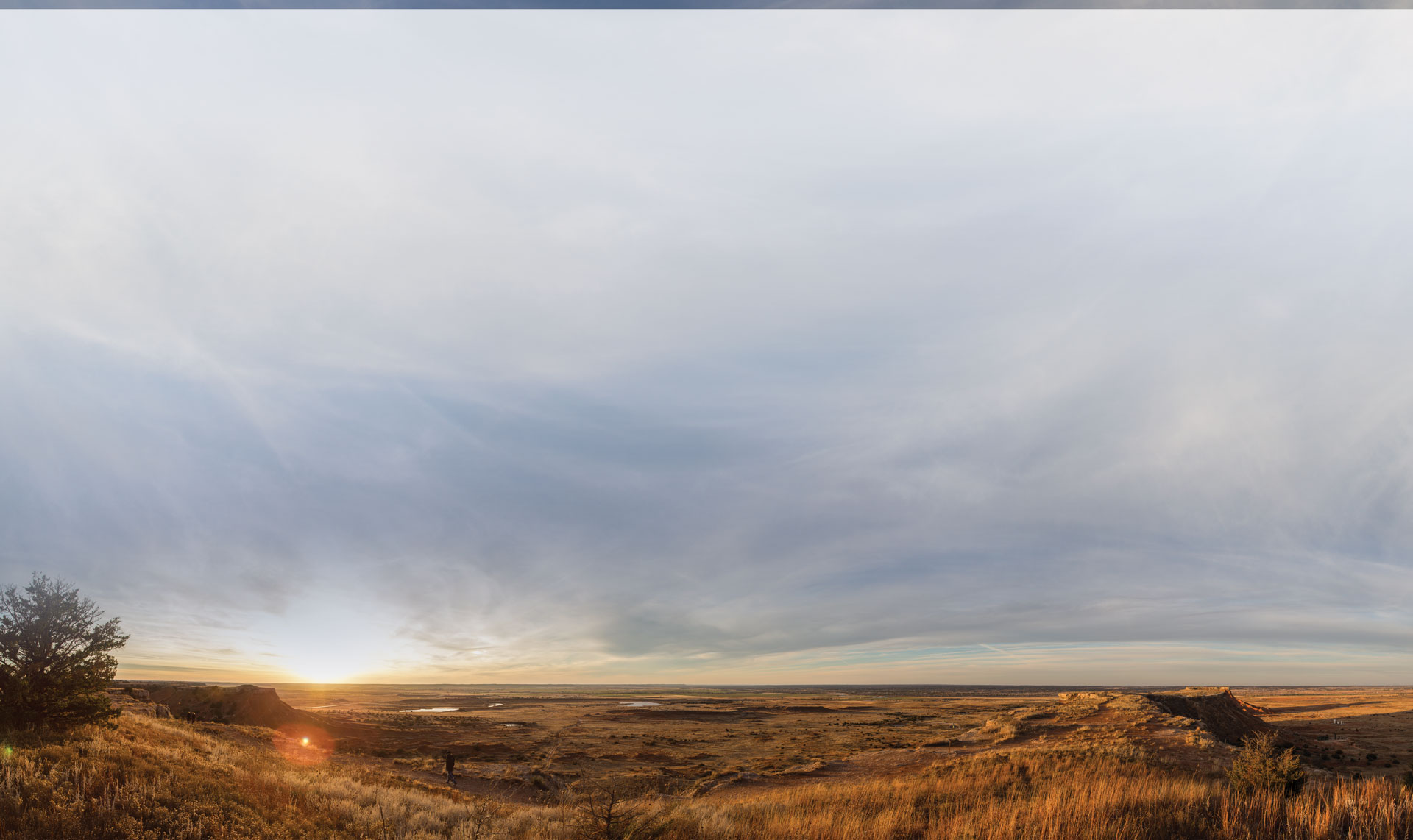

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation covers 3 million acres and includes most of the city of Tulsa. Within a short time, the decision implicated hundreds of other cases beyond that of Jimcy McGirt and expanded to all of the “Five Tribes” with a shared legal history: the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole nations. Two federal district courts have primary jurisdiction in the area, the Eastern District and Northern District of Oklahoma. Overall, Oklahoma includes 39 federally recognized tribes, and McGirt standards have been extended by the courts to at least four other tribal nations. The state’s population is 9.4% Native American, according to the most recent census, the second-highest percentage in the country behind Alaska. Indian Country covers about 43% of Oklahoma’s land.

As happens across the country with criminal cases on Native American lands and involving Native Americans, the U.S. attorney takes over the prosecution under the Major Crimes Act if a serious crime such as murder, rape, burglary or felony child abuse is alleged. Tribal justice systems prosecute lesser crimes that carry a sentence of up to three years, or up to nine years on multiple counts. Non-Native American defendants accused of felony or misdemeanor crimes against Native Americans are prosecuted in federal court (with the exception of some Violence Against Women Act crimes that tribes may handle), while states have authority over crimes when both the defendant and victim are non-Native American on native territory.

The implications of the McGirt decision meant that the state of Oklahoma would have to close out all pending cases involving Native Americans in Indian Country.

"It is the most significant Supreme Court Indian law case in well over 100 years." –Robert J. Miller

“We had cases happening that weekend,” Cozzoni says. “And there were cases new to us—people awaiting trial over in the state. That first month of indictments was a long grand jury. The state would set McGirt dockets and dismiss them, and we’d get about 50 to 80 at a time for review,” she says. She’d send someone out to grab boxes of evidence. “It was all hands on deck,” she adds.

Civil attorneys in the Northern District moved to help with the criminal docket. A dozen “detail” attorneys from other federal district courts across the country were loaned on six-month assignments starting on Aug. 20, 2020, says Cozzoni, and from Jan. 1 through Oct. 1, 2020, two dozen “term” attorneys outside the agency were also engaged to help.

Now, 21 months later, five permanent positions have been added. Probation offices, victim services, the FBI, IT systems and the courts all had to scale up as well. Cooperative cross-commissions were established to give enforcement authority to policing agencies at all levels—from the state highway patrol to federal agents.

“We just have to work together. It’s a new scenario. The crimes are not new. But it is a new way of dealing with them. The federal system is different than the state system. The tribal system is different than the state system. It’s just going to take a little bit of time to adjust to differences in the systems. For everybody,” Cozzoni says.

Although serious crimes such as drug cases, gun cases and bank robberies were not new, the U.S. attorney’s office began handling substantially more domestic violence and child sexual abuse cases. Prior to McGirt, the Northern District Court normally indicted about 200 cases per fiscal year. In the fiscal year 2021, beginning Oct. 1, 2020, indictments reached a total of 544—not an increase in criminal activity, but a reallocation of cases from the state, Cozzoni says.

In September, the Judicial Conference, a policymaking body over which Chief Justice Roberts presides, recommended that Congress create two new Article III judgeships for the Northern District of Oklahoma and three for the Eastern District to accommodate the increased workload from McGirt.

Ripple effects continued to flow. The tribal nations began transforming their courts. Defense attorneys and prisoners sought post-conviction reviews. Issues beyond criminal jurisdiction began to find McGirt in their crosshairs—from taxation to surface mining rights.

“It is the most significant Supreme Court Indian law case in well over 100 years,” says Robert J. Miller, a professor of Indian law at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, a tribal judge and co-author of a forthcoming book on the McGirt case. “Article VI of the Constitution, the supremacy clause, also called the ‘treaty clause,’ says any treaty made or which shall be made is the supreme law of the land. The 1866 treaty between one sovereign nation, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and the United States, is being honored. Wow,” Miller says.

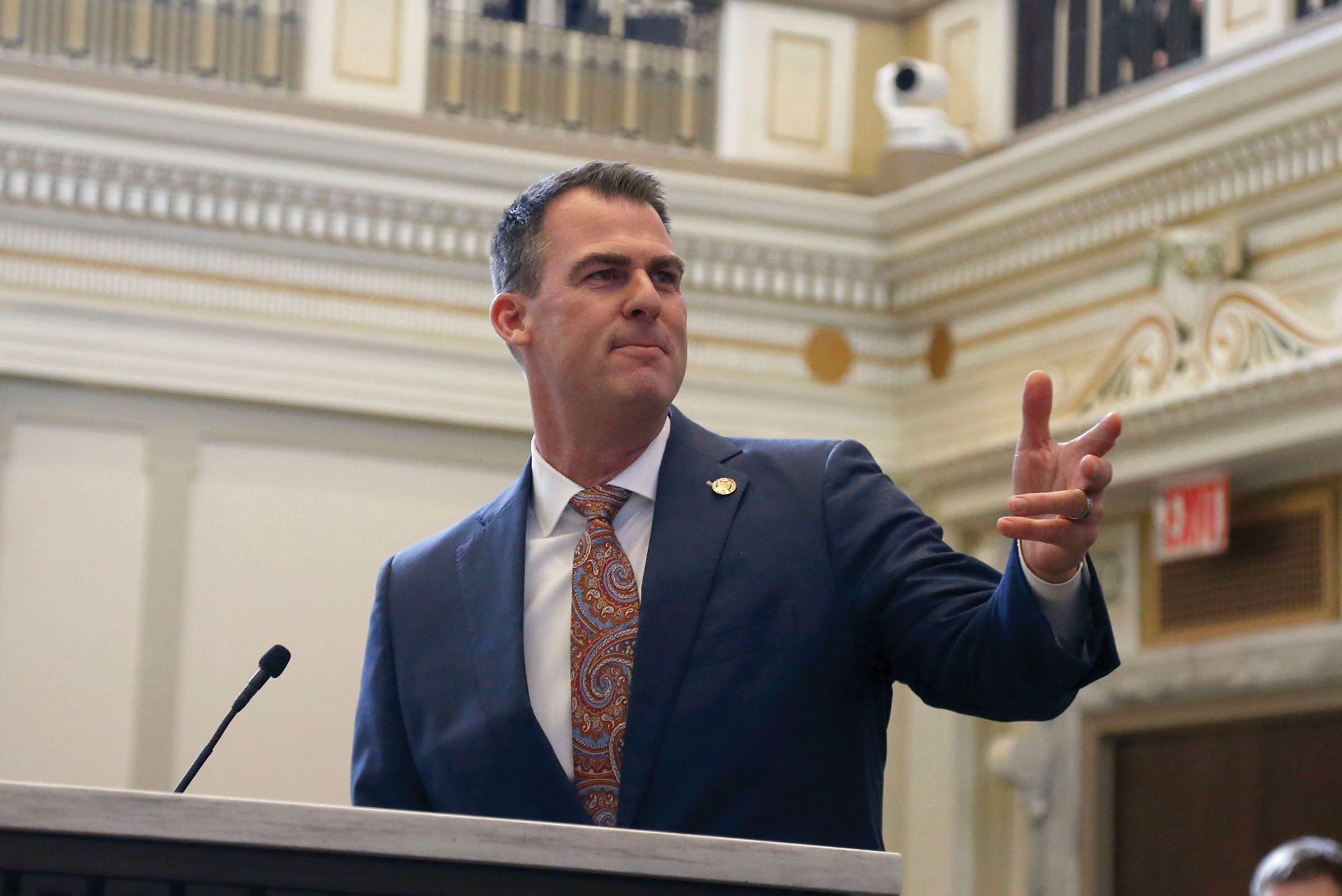

Fierce opposition to the McGirt decision also has arisen from officials in Oklahoma, including Gov. Kevin Stitt, the state attorney general and district attorneys.

“McGirt remains a threat to the future of our state,” Gov. Stitt said in a speech in Tulsa in August, 13 months after the ruling. The governor announced that Oklahoma would take action to overturn the ruling. “And let me be clear: When we say ‘overturn the McGirt ruling,’ what we’re seeking is the complete restoration of Oklahoma sovereignty, the way we’ve all known it for the last 114 years,” Stitt said.

In December 2021, after an editorial with the headline “How to Get Away with Manslaughter” appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Stitt tweeted its last line: “Is this justice, Justice Gorsuch?”

Approximately 45 petitions for certiorari on McGirt-related criminal cases have been filed before the high court, according to Ryan Leonard, who is Stitt’s special counsel for Native American affairs and an attorney with Edinger Leonard & Blakley in Oklahoma City.

“McGirt calls into question the fundamental sovereignty of the state of Oklahoma in a way that no other act of Congress or court decision has since the founding of the republic,” Leonard says.

Although the majority opinion in McGirt states that Congress is the venue for securing a remedy, Leonard rejects that as a possibility. “The remedy is for the court to reverse its incorrect decision. Everybody, for over a century, believed that the reservations had been disestablished. The bottom line is the court created this situation, and only the court can solve it,” he says.

In January, the court put one case on its spring docket, Oklahoma v. Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta. In it, the state sought to revisit and overturn McGirt. Seven amicus curiae briefs were filed both in support (four) and opposition (three). The court agreed to hear the case, but it confined its review to the state’s jurisdiction in Indian Country over a non-Native defendant accused of a crime against a Native victim, which is currently a federal court matter. The court did not agree to reconsider McGirt. Oral arguments, this time with Justice Amy Coney Barrett seated, are scheduled for April.

According to Leonard, if the Supreme Court fails to reverse McGirt, Oklahoma will seek to limit it. “We believe if McGirt remains the law of the land, it was a narrow decision because that’s exactly what the decision said. So the state will aggressively resist any and all attempts, whether it be by the federal government, the tribes or any other party, to expand McGirt beyond its narrow ruling,” he says.

Tulsa County District Attorney Stephen Kunzweiler feels just as passionately that the Supreme Court should reverse its opinion. He details a stream of damages that he feels McGirt provoked.

“The immediate and most pressing concern was how do you know if someone is an Indian?” Kunzweiler says. He calls it a race-based question that could expose an officer to liability. “The only other time I asked race-based questions was if I filed a hate crime,” Kunzweiler adds. (Scholars of Indian law describe Native American status as a political category based on tribal enrollment, not a racial classification.)

Kunzweiler believes McGirt harms victims, in some cases by requiring the state to dismiss cases and transfer them to a new jurisdiction where they will have to be revisited, something he says victims find confusing. “Those were the toughest conversations I have had in my life,” Kunzweiler says.

He points to specific cases since McGirt that he believes have been mishandled, and he is one of the signers of an amicus brief in Castro-Huerta, in which the state’s district attorneys listed seven instances in which prosecutors feel charges should have been filed but were not.

Criminal defendants already have found their options for post-conviction relief under McGirt sharply curtailed because of a decision by the Oklahoma Criminal Court of Appeals. Initially, state courts extended McGirt to post-conviction cases, says Adam Banner, a criminal defense attorney in Oklahoma City and an ABA Journal contributor.

But in a distinct pivot, the court declared in August 2021 in the case of Matloff v. Wallace that it would not review cases retroactively if they were final at the time of the McGirt ruling, calling it a state procedural matter.

Banner questions the decision. “We have a blanket understanding of jurisdiction—jurisdiction can be raised at any time, you never waive that,” he says. In January, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal on retroactivity in Parish v. Oklahoma.

Like the federal government, the tribal nations in Oklahoma have scaled up and expanded their operations.

“Prior to McGirt, in 2019, I had one full-time prosecutor who did both juvenile and criminal cases. Today, I have eight full-time prosecutors,” says Sara Hill, attorney general for the Cherokee Nation.

The Cherokee Nation, one of the two largest tribal nations in the U.S., has approximately 140,000 citizens living on the Cherokee lands that extend across 14 counties in northeastern Oklahoma. The McGirt holding was applied to the Cherokee Nation by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals in March 2021.

As a result, the Cherokee Nation is responsible for prosecuting cases with Native Americans on its lands that do not fall under the purview of the U.S. attorney. The Cherokee Nation has spent $30 million to expand its criminal justice system post-McGirt, Hill says. In 2021, her office handled more than 3,000 cases—nearly 50 times the 60 to 65 cases in the pre-McGirt year of 2019.

The Cherokee Nation increased its judicial bench from one to three judges. Decades-old cross-deputations were reinvigorated with new communications and outreach to local law enforcement. “In the last year, we’ve made huge progress on that—I think all of the tribes have,” Hill says.

"This is the strongest declaration of our tribe's sovereignty in our lives. This is an indescribably big deal." –Sara Hill

Still, she’s frustrated with Oklahoma’s efforts to overturn McGirt. “It seems like Oklahoma is putting a lot of energy into the wrong things. Oklahoma could be working with the tribes to assure a smooth system of transition,” she says. “Collaborative and cooperative is not the order of the day. It definitely makes it more complicated than it has to be,” Hill says.

Hill believes that the tribes and the state could enter intergovernmental agreements on criminal jurisdiction, perhaps with the help of a congressional measure introduced in May 2021 by U.S. Rep. Tom Cole, R-Okla., to permit more direct compacting authority between the Cherokee Nation and the state without federal involvement. The legislation has not advanced since then, but there are already hundreds of compacts—intergovernmental agreements between tribal nations and the state—that have been negotiated over the years on a variety of legal and jurisdictional issues and that are inscribed by the Oklahoma Secretary of State.

Hill thinks the tribal nation and the state have resources to offer each other—the Cherokee Nation has special behavioral health programs; the state has holding facilities for criminal suspects.

Stacy Leeds, a professor of law at Arizona State University, a scholar of Indian law and now a Muscogee (Creek) Nation judge, sees the first two years following McGirt as stabilization as the tribal courts hire more people, increase their capacity and settle into a new future.

“All of the states out West that have sizable Indian Countries inside their state borders have been doing this all along, and Oklahoma was the outlier,” Leeds says. “This takes Oklahoma and puts them on the same footing.”

Eighty percent to 90% of what happens in the Oklahoma state courts is unaffected, Leeds says. What is different is that the tribal courts are able to develop their own system of justice.

“That profound opportunity to govern is reaffirmed,” Leeds says. “But there are just the day-to-day mechanics—you have three or four clerks, and they are used to having really small caseloads; and then just the mechanics of who’s going to scan all this stuff in, and how you get everything set for a docket. So it’s been a pretty remarkable feat so far.”

In the ABA webinar Final Notice-Past Due: The Challenges and Cost of Justice in the Wake of McGirt v. Oklahoma, Muscogee (Creek) Nation Judge Gregory Bigler described how the sheer costs of incarceration had exploded.

“We went from 150 to 200 criminal cases for a year to up to 2,000. Where are we going to house them?” Bigler asked. With daily incarceration fees of $45 to $75 per person, the costs in a single day can be more than the tribal nation paid previously in a year. That, Bigler said, presents the larger question of how tribes can raise revenue.

The McGirt case may also be felt in civil areas that are beginning to percolate with more regularity.

What’s not affected are private property rights or land ownership inside re-recognized tribal boundaries, Miller explains. Separate laws in place before McGirt also govern areas such as probate proceedings of Native Americans and oil and gas rights on reservations.

But taxation already is shifting. Under existing court rulings and laws predating McGirt, the state may not collect income taxes from Native Americans who live and work in Indian Country. From the date of McGirt to November 2021, more than 5,000 people had claimed an Indian Country tax exemption, according to information provided to the nonprofit news site NonDoc by Cassandra Sweetman, public information and press liaison for the Oklahoma Tax Commission.

A report by the commission in September 2020 estimated that the state would lose $72.7 million annually in income tax revenue and another $132 million in sales and use tax revenue. “That’s probably the No. 1 thing Oklahoma is upset about,” Miller says.

Miller also points to issues that may arise with the Indian Child Welfare Act, which holds that tribes have exclusive jurisdiction over foster care and adoption of American Indian children if they are domiciled on the reservation. “So the size of the reservation really impacts your caseload for child welfare,” he says.

Surface mining, such as coal exploration rights, arose as an issue after the U.S. Department of the Interior issued a notice in May 2021 that the state could not exercise regulatory jurisdiction over surface mining on Muscogee (Creek) Nation lands because of McGirt. The state sued, and while the federal district judge denied Oklahoma’s motion for a preliminary injunction in December, he criticized “the havoc flowing from the McGirt decision.”

Other areas like hunting and fishing rights, gaming and license plates might also be affected, says Mike McBride III, who chairs the Indian Law Gaming Practice at Crowe & Dunlevy in Tulsa.

“There’s an importance for the tribes and state to get along. We’re all neighbors. And tribes are not going anywhere,” McBride says. “They are huge economic engines in terms of economic development and federal programs, federal dollars that come in. They have a huge multiplier effect on Oklahoma’s economy. So it really behooves us to all work together and to sort through the re-recognition of reservation boundaries as the result of McGirt,” he says.

For now, the transformation unleashed by McGirt is a work in progress. “We’re in limbo. It continues to evolve,” District Attorney Kunzweiler says.

“Stay tuned,” suggests Muscogee (Creek) Nation Judge Leeds.

But for Cherokee Nation Attorney General Hill, who was recently named one of 10 “People to Watch” by the Tulsa World, it’s invigorating.

“You’ve reached aftermath central here. I’m a Cherokee citizen, and there is hardly a more exciting time to be here than today,” Hill says. “This is the strongest declaration of our tribe’s sovereignty in our lives. This is an indescribably big deal, and to be here and to have an opportunity to stand up for our tribe when they need us—what Cherokee lawyer wouldn’t want to be part of that?”

Cynthia L. Cooper is a journalist and lawyer living in New York City.