Jailhouse Warehouse: The nation's jails are housing more mentally ill people than hospitals

Photography by Sara Stathas

The audience sitting in the gymnasium bleachers is charged with excitement as the graduation speaker approaches the podium. Student artwork hangs on the cinder block walls nearby, along with handwritten signs that declare “The harder I work, the luckier I get” and “Failing to prepare is preparing to fail.”

The graduating class of 86 men is dressed in two-piece khaki scrubs branded with DOC on the back. They are detainees inside the Cook County Jail and all have a serious mental illness.

There are no family members here to celebrate with them, just Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart and warden Nneka Jones Tapia, who sit in the first row with guards and mental health professionals behind them.

The speaker, a man with a shaved head and tattoos on his arms and face, speaks of his father’s death, his mother’s drug use and his anger, gang involvement, depression, addiction and, most importantly, his transformation since starting a photography class at the jail’s 2-year-old Mental Health Transition Center.

“It’s time for me to let go of the fake me and embrace the real me,” the speaker says. “Thank you, Sheriff Dart. You are our gatekeeper.”

Everybody in the gym stands, clapping and hooting.

CARE AND TREATMENT

The ceremony celebrating completion of photography and drumming classes illustrates how Dart is trying to bring programs and treatment to low-level offenders with mental health issues—an approach that is catching on throughout the country. Dart’s goal is to help move them out of the criminal justice system and into treatment through a wide-ranging spectrum of programs. A handful of counties are adopting a similar holistic approach. “We are putting sick people in jail,” Dart says. “Would we do that with another disease? We are criminalizing mental illness instead of treating it.”

In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Estelle v. Gamble that prisons are constitutionally required to provide adequate medical care to inmates. That makes detainees the only group of Americans with a right to health care, and that includes mental health care. In recent years, moves by Dart and others who run jails have worked to support that right.

In his 10-year tenure, Dart has made unconventional moves, including hiring Tapia as warden, the first clinical psychologist to serve as executive director of a major U.S. jail. “What she brings to it is another skill set,” Dart says. “It is a nuanced way that she has added additional emphasis on [mental health]. I have an additional person who completely gets it.”

“He’s the type of guy that gets ideas when he is brushing his teeth,” Tapia says of Dart.

Those ideas include crisis intervention training for sheriff’s department officers and 911 dispatchers, increasing the use of electronic monitoring for low-level offenders, especially those with mental illness, and diverting arrestees with behavioral health issues from jails or emergency rooms. He also wants to create daily programs for low-level offenders, such as group therapy, individual counseling, job training and art therapy like cooking, drumming, gardening and photography.

Despite the good intentions of these programs, Cook County Jail still is an institution steeped in problems. In 2008, the U.S. Department of Justice cited the jail for violating inmates’ constitutional rights, including excessive use of force by staff, inadequate fire safety and sanitation, failure to protect inmates from harming one another, and inadequate medical and mental health care. The jail remains under federal watch.

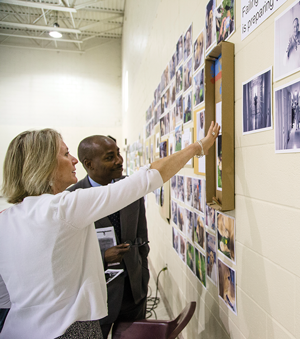

Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart and jail warden Nneka Jones Tapia celebrate detainees’ graduation from classes in photography and drumming at the Mental Health Transition Center.

The jail is one of America’s largest pretrial detention centers where those arrested and unable to make bail remain, presumed innocent, until their cases are adjudicated. About 2,200 of the 8,800 detainees have a mental health diagnosis, prompting many to call it America’s largest mental health institution. By comparison, Bellevue Hospital Center in New York City is considered the nation’s largest mental health hospital with 330 psychiatric beds.

Overcrowded jails housing mentally ill people are not unique to Chicago. Across the nation, about 383,000 inmates with serious mental illness sit in jails and state prisons. That’s 10 times as many people as in state hospitals, according to the nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center. “It is an omnipresent tragedy that there is an overrepresentation of people with mental illness in jails,” says Dr. Fred Osher, the Charleston, South Carolina-based director of health systems and services policy at the Council of State Governments Justice Center. Many who have been arrested do not receive regular psychiatric care or counseling on the outside, often because of a lack of adequate insurance.

“Their violating the law often is linked to their mental health issues. That’s different from people who are making bad choices,” says attorney Jennifer Vollen-Katz of the John Howard Association of Illinois, a Chicago-based nonprofit devoted to prison reform. “If we are more mindful of that, we might get closer to getting people into the right systems where we address their needs.”

THE SHERIFF’S CRUSADE

With graying hair and rimless eyeglasses, Dart looks more like an English professor than a sheriff. He wears beige chinos and a blue checked shirt, his holster and gun visible on his back, and his sheriff’s badge on his belt. A flip phone hides in his pocket, and several colorful, braided-yarn bracelets made by his five children rest on his wrists.

Despite his law enforcement responsibilities and his crusade to improve mental health treatment, the 54-year-old sheriff does not have a background in mental health, medicine or even police work. (He has, however, received the same firearms training as law enforcement.) The Chicago native is a Jesuit-educated, voluntarily inactive lawyer who served in the state legislature before being elected sheriff and focusing on mental health. It has been an issue as long as he has been sheriff, Dart says. “But it’s only been the last two or three years that the world has woken up to it.”

Although he is not the only one taking this approach, Dart has perhaps been the loudest American sheriff on the issue of mental health, writing op-eds in the Chicago Tribune and Wall Street Journal. “The voice that [Dart] has given—that this is a major crisis, that it is a tragedy on our hands—is huge,” says Gilbert Gonzales, director of the Bexar County Mental Health Department in San Antonio.

“If I am going to be in charge of all these ill people, then I have to treat them like patients,” Dart says.

At 9:30 on a Monday morning, a slight, 20-year-old man stands at a counter. Charged with possession of a firearm and cannabis, he’s deep inside the main building of the Cook County Jail, an 87-year-old, 4 million-square-foot compound. Intake sits in the labyrinth of deliberately unmarked tunnels connecting the complex of buildings that cover 96 acres. There’s no natural light here, making it dark despite the white walls inside the pens. Down the hall, two men with profound mental illness sit in solitary cells behind metal fencing, each shouting at their florid hallucinations.

Maggie Bojko stands on the opposite side of the counter. A behavioral health specialist with the sheriff’s office, she has a conversation with the man as part of a mandatory mental health screening for all new arrestees. She asks why he carries a gun. “For protection. This is Chicago.”

“You been here before?” Her voice is kind and warm.

“No. This is my first time.” He swallows hard, looking wide-eyed and boyish.

“Do you have mental health issues? Depression? Bipolar?” she asks.

“I am not bipolar, but I am schizophrenic.” He pauses, timidly. “A little bit.”

They talk about counseling and medication—he has neither. His mother is his only family support. Bojko hands him a hot-pink card with numbers for suicide hotlines and 24-hour social service agencies. This move—the first of many offerings of help for mental illness—plants the seeds for the support he’ll need when he gets out.

The man says thank you and swallows hard again, then walks away, waiting for the sandwich he’ll receive before seeing the pretrial judge that afternoon.

Detainees, along with jail officials, listen to stories from their peers about challenges and transformation. “It’s time for me to let go of the fake me and embrace the real me,” one inmate said.

“Historically, this is a population we couldn’t even get near, couldn’t get to interact with because they went right to court,” says Elli Montgomery, Cook County director of mental health advocacy and policy. “The sheriff is making sure we will offer support to help with basic needs—housing, medical, job training, rides and religious services.”

Though Cook County has a 12-year-old mental health court, a minute percentage of people with mental health issues go there, says Cara Smith, Cook County’s chief strategy officer. The reason is that getting into mental health court requires defendants to plead guilty and be willing to go into treatment, and they cannot be charged with a violent crime, among other restrictions. “With the restrictions, it doesn’t seem to help the people who need it most,” Smith says.

RESOURCE CRISIS

The U.S. has never had a national mental-health system. That responsibility falls on the states, which 100 years ago funded the first asylums and mental health hospitals. In the 1960s, deinstitutionalization became a buzzword as the facilities faced political and financial pressure to close. Patients were released from state institutions with plans for community treatment in smaller centers. It sounded ideal, but community services never kept up with demand. Many people ended up on the streets, unable to receive public services for treatment or afford private care.

Fifty years later, resources remain scarce and continue to dry up. To this day, when communities suffer hard times, mental health funding usually falls victim to cuts. From 2009 to 2012, state funding for mental health dropped by $1.6 billion—$187 million in Illinois alone, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

So jails often become de facto mental health service providers, forcing administrators to figure out how to handle the situation. Dart admits he has no master vision for the jail’s mental health program. “I truly am making it up every day. I can’t wait for a grand plan here,” he says. “Grand-plan thinking is what is killing us. It’s paralysis. I just start doing it.”

Dart gets what he wants. He can reallocate resources toward supporting mental health issues without requiring approval for line-item changes in his budget. “I really have to answer to no one but the voters,” he says.

Cook County encompasses the politically charged city of Chicago, where Mayor Rahm Emanuel has shuttered half of the mental health clinics in recent years. (If Dart, a Democrat, throws his hat into the mayoral race, Emanuel will likely be his foe in a town where the primary often determines the election.) Cook County itself sits within the financially troubled state of Illinois, which operated without a budget for more than a year, choking off funding for many agencies. As a result, services for those with mental illness from the city and state are vanishing.

“Our state can’t even come up with a budget,” says Cook County Commissioner Richard Boykin. “It’s done irreparable harm at the social services level. Several providers have closed their doors or laid off workers. People shouldn’t have to be incarcerated to get services.”

NATIONAL EFFORTS

Faced with little support from state governments, the holistic mindset of Dart and a few others is a slow, yet growing movement around the country. In August, the American Bar Association passed revisions to the 10-part Criminal Justice Mental Health Standards, originally written in 1984, that recognize the need to change with the times. The new standards reflect changes in the law and best practices, ranging from the roles defense attorneys, prosecutors and judges play in cases involving people with mental illness to the addition of specialized courts and the need for service networks for defendants.

“The document recommends education for all stakeholders in the field and aims to change the system,” says Associate Administrative Judge Steve Leifman of the 11th Judicial Circuit of Florida in Miami-Dade County, who sits on the ABA committee that revised the standards.

Meanwhile, a collaboration among the National Association of Counties, the Council of State Governments Justice Center and the American Psychiatric Foundations aims to share those lessons with others working to move in the same direction. This is happening through the Stepping Up Initiative, a year-old group that encourages counties to work with state and local agencies and others to develop a new way of handling mentally ill detainees. At press time, 308 counties had passed resolutions supporting the group’s efforts.

However, even though counties have common goals and face similarly tight financial constraints, each county must negotiate specific political priorities in its multipronged approaches. “No one county has the special sauce yet,” says Osher, a leader at Stepping Up. “Everyone does things a little different and has to find their own way.”

To develop programs that address specific local needs, county officials must look at a variety of numbers—arrests, locations, available services and more. “We are spending a good amount of time and energy analyzing data. It really opens up your eyes,” Dart says. For example, Cook County used data to map out areas where law enforcement officers go most frequently to handle mental health cases. “Then, we layer over that services available,” Dart says, “so we can get more critical analysis of where services should be.”

Data also helped the county see the stumbling blocks, such as fees for expunging or sealing arrest records. According to the sheriff’s office, 17 percent of the more than 70,000 people who enter Cook County Jail every year get released as a result of having their cases dropped or being found not guilty. “Many of the people arrested have mental health issues and they are poor people. We need people to have jobs, and a mark on their record can be a roadblock,” Dart says.

He pushed for Illinois House Bill 6238, which creates a pilot program in Cook County to remove the $120 fee for expungement and sealing arrest records. The bill also opens up who can qualify to have their name cleared. It was signed by Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner in August.

TEXAS HOLD ’EM

Data analysis also led to changes in Texas.

Gonzales, the mental health director in Bexar County says that in the early 2000s, “the get-tough-on-crime laws and the lock-’em-up mentality that arrested everyone with a drug issue and even a small amount of marijuana filled San Antonio’s jails and emergency rooms beyond capacity.”

Desperate for solutions, county officials examined the data—from the number of homeless to police response time and the cost of processing detainees through the system. They found that the jails, hospitals, courts, police and mental health department often dealt with the same people—those with mental illness.

If various agencies could coordinate efforts, the county would save money. And if people with mental health or alcohol issues could be diverted out of jails and ERs and into specialized treatment, they’d be better off—and potentially more productive citizens. To that end, Gonzales helped bring together a multidisciplinary consortium of more than 60 community stakeholders.

“Getting buy-in can be incredibly frustrating, to put it mildly,” says Gonzales, who has led the communitywide jail diversion services. “But we rely on data. We can show how a difference is being made. We can show cost-benefit ratios that make sense. And it’s hard to argue with something that’s working.”

With $6 million in state funds, the county built the publicly funded Roberto L. Jimenez MD Restoration Center, offering services to stabilize people with mental illness—including a 48-hour inpatient psychiatric unit, an outpatient unit, a detox center and sobering services. The center sits across railroad tracks from the publicly and privately funded Haven for Hope, a rehabilitation campus and low-barrier homeless camp.

Now, police screen those they arrest for nonviolent, minor-offense mental health issues, the first of four levels of screenings. If any red flags are raised, such as previous suicide attempts or self-inflicted injuries, arrestees are brought to the restoration center for treatment instead of being taken to jail, says Gonzales, also a clinical psychologist. Those who are indigent immediately also are assigned a public defender and a licensed mental health counselor.

The once-overcrowded jail now has empty beds, and the streets of San Antonio have fewer homeless people, Gonzales says.

MONEY TALKS

Substantial savings come from getting police back on the streets within minutes, instead of hours after an arrest, Gonzales notes. The process of intake at the center frees up officer time. In Bexar County, it costs $2,295 for booking and placing an arrestee in jail. “If the officer can take the individual who is charged with a misdemeanor and bring them to treatment, the cost is about $350 and they are less likely to return to jail,” Gonzales says.

Photos taken by detainee students are on display in the jail.

As the number of detainees dropped and the loads of police, judges and hospital emergency rooms lightened, the county has saved an estimated $10 million annually, he adds.

Critics worry, however, that treatment is not enough, and that some with more serious mental illness might return to a life of more serious crime once released. And they point out that these systems demand a considerable investment up front to build the facilities and infrastructure. Moreover, treating people with mental illness is not cheap. In Bexar County’s mental health treatment center, for instance, it costs $143 per day per person for treatment and medication.

But it’s a worthy investment if it keeps the detainees from coming back, Gonzales says, and ultimately that puts money back into the community and out of the criminal justice system. “We have a solution to this problem,” he adds. “It’s called treatment.”

Data-based thinking helped Miami-Dade develop its Eleventh Judicial Circuit Criminal Mental Health Project in 2000. The wide-ranging program coordinates dozens of community stakeholders. For instance, all 4,700 officers from the county and its 36 local police departments receive mental health crisis-intervention training.

Data from 2010 to 2015 collected by Miami and Miami-Dade officers show those two agencies handled 60,427 mental health calls, yet made only 119 arrests, says Miami-Dade judge Leifman, who spearheads the program. “We were actually able to close one of the local jails,” he says. “This enabled the county to save $12 million and we are investing some of that money into other programs. Rarely is there cost savings, just shifting.”

Another of Miami-Dade’s reforms includes working with nonviolent offenders deemed incompetent to stand trial. “Typically, if you are incompetent, you go to forensic restoration to become fit to stand trial, which costs $60,000 to $70,000 per person. In Florida, we spend $135 million to restore competency,” Leifman says.

Whatever the outcome of their cases, those arrested often leave the system with little if any access to mental health treatment. This tends to result in the revolving door between homelessness, mental health facilities and jail.

The Miami-Dade program involves community reintegration. “It is one-third cheaper, one-third quicker and we have very little if any recidivism,” Leifman says. “They stay with the same provider that we hook them up with, and we work with them to get them into recovery.”

INTO THE COMMUNITY

In the discharge lounge of Cook County Jail, the efforts to set up mental health support that began during the intake process are spelled out. A caseworker spends about 2½ hours covering the basics with each person being released—housing, medical needs, prescriptions. They also get a crisis hotline number and information covering topics such as how to get a bus pass and state ID.

The caseworker also makes sure the person has health insurance lined up. About 15,000 detainees have signed up for CountyCare, a low-income Affordable Care Act expansion of Medicaid. This ensures that their treatment plan after jail—including group therapy, doctors’ appointments and medication—will be covered, according to Dart.

The caseworkers make arrangements for rides by a friend or family member to make sure the detainee goes to someone’s home or a shelter instead of directly back to the streets. And once detainees are released, the county provides free rides to doctor appointments and job interviews using a donated van. “Previously, we would just let them go and that was that. I think that was the height of foolishness,” Dart says. “We stay with them, even after they leave.”

Every other Monday, some “alumni” of Cook County’s Mental Health Transition Center come back to the jail—on their own terms. This is part of a support group started under Dart; and today, six men show up to review how things are going. “Those guys who come back and do check in, they are the ones doing really well,” says Sharon Latiker, a community outreach manager.

One man has a job interview lined up. Two are studying to become ministers and invite the others to listen to their first sermons. Another is celebrating 18 months of sobriety. The lessons they learned while in the program during detention—to stay away from people, places and things that trigger high-risk behavior—are reinforced.

Former detainee David was released six weeks earlier after serving 10 months for assault. He says he now focuses on gratitude, that he already has all he needs to be happy. “Entitlement does not make you happy. Asking for happiness, wanting more does not make you happy,” David says. “Be grateful. We are released. Be grateful.”

“That is powerful. That gives me chills,” says Lee, an alum who wears a white T-shirt and black shorts. “Cold-blooded truth.”

“The Mental Health Transitional Center has changed me,” David says. “This program has saved me.”

Julianne Hill is a freelance writer based in Chicago.

This article originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: "Jailhouse Warehouse: The nation’s jails are housing more mentally ill people than hospitals—yet some mentally ill people than hospitals—yet some institutions are reversing the trend through programs that emphasize treatment instead of punishment."