IOLTA programs find new funding to support legal services

Betty Balli Torres: “In many states, the bottom fell out of IOLTA. …We saw the light and looked for other means.”

When the Federal Reserve announced in December 2008 that it was lowering the interest rate to virtually zero, it had the effect of nearly zeroing out a mainstay in funding civil legal services for the poor: interest on lawyers’ trust accounts, aka IOLTA.

“In many states, the bottom fell out of IOLTA,” says Betty Balli Torres, executive director of the Texas Access to Justice Foundation, which distributes funds to 89 legal aid offices throughout the state. Steady annual revenues of about $28 million suddenly dropped by 75 percent. “We saw the light and looked for other means,” she says.

Nationwide, IOLTA funding dropped from $371 million in 2007 to $93.2 million in 2011, according to the ABA Commission on IOLTA.

With help from the Texas Supreme Court, especially lobbying efforts by Chief Justice Wallace B. Jefferson, Torres got a one-time $20 million boost from the legislature in 2009. But rates stayed low the following year, and they have remained so.

“We found ourselves back the next legislative session for funding yet again,” Torres says. The agency was added as an appropriation, getting $17.6 million in 2011, and expectations are that the program will remain in the budget until interest rates start to go up again.

The money from the legislature has been enough to keep the infrastructure viable while Torres and others work on new efforts to raise additional money. IOLTA programs around the country have scrambled for other funding sources—and while they’re not where they once were, for many the effort is paying off.

The change was like going off a cliff for agencies that by 2008 had become relatively flush with funds because of healthy interest rates and, particularly, the increase in comparability rules requiring banks to give IOLTA funds the same rates as other borrowers.

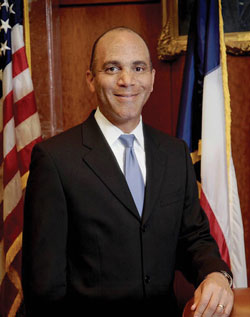

Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Wallace B. Jefferson

THE NEW POOR

IOLTA is dead. Long live IOLTA. The brand remains the same, but nationwide, IOLTA programs have been remaking themselves in the face of a double whammy: severely diminished funding from their traditional source and a significant increase in the number of people qualifying for free civil legal services.

“Demand is through the roof,” says James J. Sandman, president of the Legal Services Corp., which saw its own congressional appropriation drop to $348 million in fiscal 2012, down from $404 million. The LSC funds legal assistance programs at the local level.

“The population eligible is now at 60 million, nearly 20 percent of the country

—an all-time high,” says Sandman. Much of that increase has been in “the new poor, as they are called, who previously couldn’t have imagined themselves ever needing or being eligible for legal services,” he says.

Having always been hungry, IOLTA programs themselves are now abjectly poor. Generous banks offer IOLTA program rates as high as 1 percent—a once laughable figure. And the Federal Reserve recently announced it expects to keep rates near zero until at least mid-2015.

Penina Lieber

By then “we will have to cut legal aid grants by 74 percent,” says Jane E. Curran, executive director of the Florida Bar Foundation, which oversees the nation’s first IOLTA program, created in 1981. “Our revenues have gone down 88 percent since rates dropped. That means cuts in programs, people, offices.”

Some states have tacked on additional court fees, professional fees and others that are steered to IOLTA programs. Many programs engage in outreach to the bar for contributions or other ways of steering funds to them.

One boon available in 10 states is residual funds from class actions now given wholly or partially to legal services. Known as cy pres, they can provide windfalls, albeit unpredictable ones. Texas’ IOLTA, for example, received $2.6 million in cy pres funds in 2010, while $1.38 million in cy pres cash flowed into the Montana Justice Foundation.

“We can no longer depend on banks because they can’t offer good interest rates,” says Penina K. Lieber, a member at Pittsburgh’s Keevican Weiss Bauerle & Hirsch who chairs the ABA Commission on IOLTA. “We’ve had to get creative and collaborative in finding alternative funding.”