In Volume Veritas

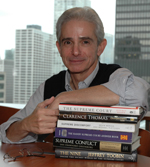

Richard Brust. Photo by Kristine Strom

Every year, tenure-seeking academics churn out stacks of highbrow books about the U.S. Supreme Court, but 2007 was a feast for the general reader. Make that the gossip-hungry general reader.

The books were of three varieties: inside history, inside politics and inside Clarence Thomas. And the court’s celebrity scribes did not disappoint: The two Jeffreys—Toobin and Rosen—joined ABC News’ Jan Crawford Greenburg and a pair of Washington Post reporters in prying open the chamber door, peering behind the red velvet curtain, or placing an ear to the Oval Office wall. Or, in the case of Thomas, putting the patient on the psychiatric couch—where he himself willingly goes in his eagerly awaited autobiography.

First, history. Charged with writing a companion to last January’s PBS series, Rosen, a George Washington University law prof and New Republic editor, instead delivered a fascinating historical jaunt, stopping at points to compare an era’s significant figures.

His thesis: That the contrast in personality between the likes of John Marshall Harlan and Hugo Black (gregarious, open-minded) and Oliver Wendell Holmes and William O. Douglas (austere, unyielding) allowed the former to coalesce with colleagues in significant majorities and consigned the latter, in great measure, to the dissent.

A tip of the hat goes to David L. Hudson Jr., author of the aptly named Handy Supreme Court Answer Book. Hudson, an ABA Journal freelancer and scholar at Vanderbilt University’s First Amendment Center, produced an accessible history in Q&A format, replete with trivia: Which justice was in a duel? Who was the first law school grad?

In the realm of politics, Greenburg and Toobin vie for best narration and juiciest tidbits regarding the court’s most recent appointments, behind-the-bench elbowing and White House intrigues. Call it a draw. CNN analyst and New Yorker editor Toobin’s The Nine offers suspenseful narrative and descriptive portraits of the justices. Its dirt: David H. Souter wept after Bush v. Gore.

Greenburg’s street-smart Supreme Conflict gives us more political tussling. Its nugget: Contrary to most observers, Thomas is mentor to ideological twin Antonin Scalia, rather than vice versa. Pick your favorite stylist.

Which brings us to Thomas. The high court’s resident Sphinx let loose with an autobiography, My Grandfather’s Son, which traces his life from birth to the now-legendary confirmation hearings. Those looking for answers to the riddle of Thomas will find only more complex puzzles.

Raised by a tough-love grandfather he calls “Daddy,” Thomas carries a hardscrabble, bootstraps philosophy through college and Yale law school in the anything-goes 1960s and ’70s.

Thomas was born to a bridge generation: after such civil rights giants as Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall, but before the successes or failures of diversity policies were realized. Choices were not always clear; the way ahead lacked guideposts.

But Thomas’ evasions will confound even the empathetic. Colleagues—white and black—are said to have dismissed him as inferior. But who these people were and how they manifested their biases is not explained.

Not so the villains of the confirmation hearings: the sneering white liberals who had to show Thomas his place. And, of course, Anita Hill, with her claims of sexual harassment. Thomas morphs himself into Tom Robinson, the defendant in To Kill a Mockingbird charged with raping a white woman: “I had lived my whole life knowing that Tom’s fate might be mine.”

Post reporters Kevin Merida and Michael Fletcher fill out the picture with their superbly reported biography, Supreme Discomfort: The Divided Soul of Clarence Thomas. The socially awkward Thomas was known to toss out ill-suited sexual references, they report, yet he was warm to strangers. Here is a man, the authors say, “at war with himself.” (Read Brust’s interview of Merida and Fletcher, “The Strong, Silent Type,” from the April 2007 ABA Journal.)

Thomas has become a Rorschach test for the nation’s angst over race and sexuality, and it’s likely to stay that way.

None of the books achieves the breakthrough status of The Brethren by Scott Armstrong and Bob Woodward, or Edward Lazarus’ tell-all Closed Chambers. But all are good reads and good rides.

Richard Brust edits the ABA Journal’s Supreme Court coverage.