Increased enforcement of immigration laws raises scam risk

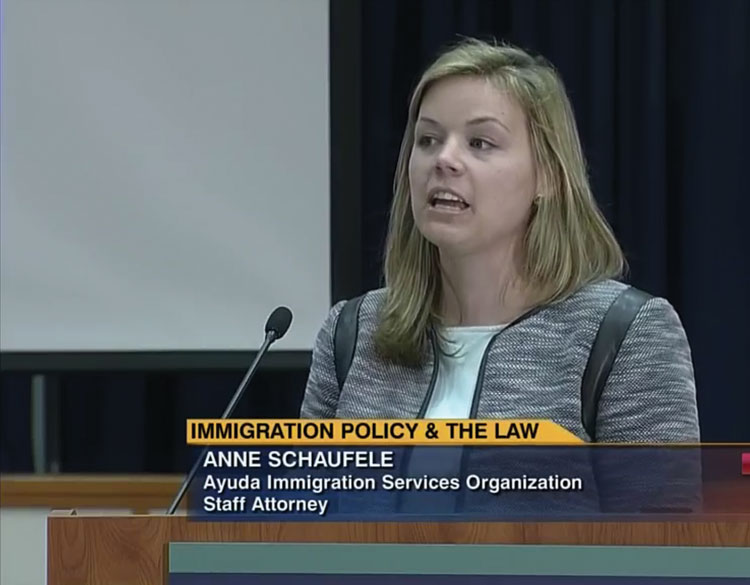

Anne Schaufele: “In the absence of licensed practitioners, ... folks are going to nonattorneys.” C-SPAN2

Though scams target immigrants of all kinds, Spanish-speaking communities have a special and very pervasive problem, thanks to notarios like the one Alicia hired. In many Latin American countries, a notario is a kind of attorney authorized to prepare documents. In the United States, notaries public may not practice law, but dishonest people exploit the similarity to fool Spanish-speaking immigrants.

In the best-case scenario, the client loses thousands of dollars—money many immigrants can’t afford to lose. At worst, the scammer may actually hurt the client’s case, up to and including getting the client deported. That’s a likely result of one common scam where the false lawyer tells undocumented clients there’s a green card available if they’ve lived in the United States for 10 years and have a child who is a citizen. No such program exists, says Vanessa Stine, who runs the Notario Fraud Project at Friends of Farmworkers, located in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

“They file affirmative asylum applications without actually explaining that to the victim, and then that puts them on track to having contact with Immigration and Customs Enforcement,” says Stine.

Like Ayuda, others who provide immigration legal services saw a dramatic increase in interest after the 2016 election. Daniel Sharp, legal director of the Central American Resource Center in Los Angeles, says the end of the year is normally the slowest time there—but not in 2016, when there were “huge numbers of people coming in.” Schaufele says Ayuda got so many calls that it started running consultation clinics. C. Mario Russell of Catholic Charities Community Services in New York City says calls to a hotline increased dramatically in early 2017.

“[There was] just an incredible number of people calling in for assistance, for directions, for guidance, for reassurance, for information, during that whole phase with the travel bans,” says Russell, the charity’s director of Immigrant and Refugee Services. “So we saw, obviously, a co-relative reaction to the administration.”

Camille Mackler: “I think always when people are afraid, they may go out looking to see if there’s anything they can do about their case. There are more people who are going to try to prey on that.” Photograph by Len Irish.

Advocates say it’s difficult to show with statistics that this leads to increased fraud, because fraud against immigrants is extremely underreported. (See “Underreporting Makes Notario Fraud Difficult to Fight”.) But they’re confident that scammers exploit people’s anxiety. For example, Mackler says immigrants living in the United States have started trying to claim asylum in Canada. An international agreement requires Canada to turn them away at border checkpoints, so they’ve been crossing by foot in rural parts of upstate New York—sometimes in dangerous winter conditions—and hoping they pass the Canadian asylum process.

It’s a dicey proposition, but Mackler says you might not know it from some of the lawyer advertising she’s seen. “Basically, they think that the U.S. has become a dangerous place for immigrants and that Canada is a welcoming place for immigrants, based in part on statements made by the heads of both countries,” she says. “I know that people are giving wrong information—or sort of like glossing over the truth, to be more charitable—to people who want to go to Canada and preying on that fear.”

That fear is on top of the vulnerability created by many immigrants’ lack of familiarity with our legal system, lack of fluent English, poverty and, in some cases, rural locations that provide few legal services. Advocates say there just aren’t enough competent, affordable attorneys to meet the need—and fake lawyers step in.

“The less you have legal services, the more you see these schemes happen,” Mackler says. “There are parts of New York I can go to where I won’t find a single immigration attorney, but I’ll find a lot of notarios.”

HELP WANTED

Of course, all of this is against the law. Every state forbids unauthorized practice of law, and a majority have laws regulating unauthorized practice of immigration law specifically. Some, especially those with large immigrant populations, have laws regulating the use and translation of “notary public,” or permitting victims to sue false lawyers. Advocates would like to expand those laws to all 50 states; Williams says the UPL statutes don’t always fully address UPIL.

But having a law on the books is one thing; enforcing it is another. Clemente Franco, a private attorney in Los Angeles who has filed several lawsuits against false lawyers, says there’s an enormous amount of fraud in that city—but maybe one prosecution every few years.

“You could throw a stone [in certain neighborhoods] and you’re probably going to hit one of these guys,” he says. “They’re operating openly.”

Schaufele says one solution might be for more municipalities to adopt a strategy that’s helped in Chicago: stings on businesses suspected of practicing immigration law without a license. Chicago requires immigration consultants to post a sign saying they cannot offer legal advice. Roughly half of businesses reviewed in 2015 and 2016 weren’t complying, Schaufele says. The stings may not eradicate businesses engaged in unauthorized law practice, but she says they may scare some out of business.

“It was a way for the city to just say, ‘You’re on our radar. We’re aware that what you’re doing is incorrect and here is a fine,’ ” she says. “That’s not going to help shut down all of the actors. But I think the well-intentioned actors, which there are plenty of, might take notice.”

Correction

Print and initial online versions of "Legal Prey," May, should have identified Vanessa Stine as a staff attorney at Friends of Farmworkers. Her Equal Justice Works fellowship ran from 2014 to 2016.The Journal regrets the error.

This article was published in the May 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Legal Prey: Increased enforcement of immigration laws has raised the risk of scams."