How prosecutors brought down Lucky Luciano

Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp and Stephen Webster

Now Kornbluth was wide awake. Levy, he knew, was in the midst of defending alleged mob boss Charles “Lucky” Luciano in that sensational vice case brought by the crime-busting special prosecutor, Thomas E. Dewey. But what could Levy possibly want from him and, more importantly, from Dorothy Calvit?

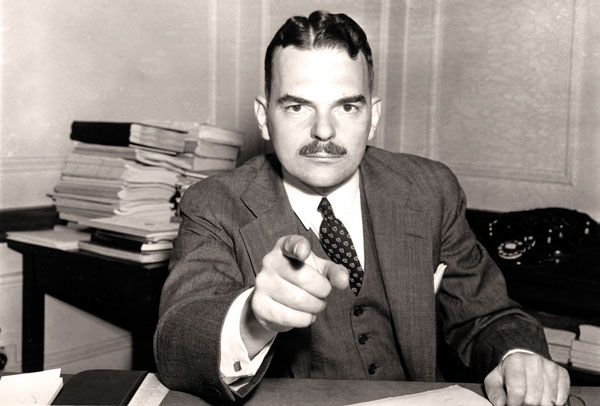

Criminal defense attorney George Morton Levy. Getty Images.

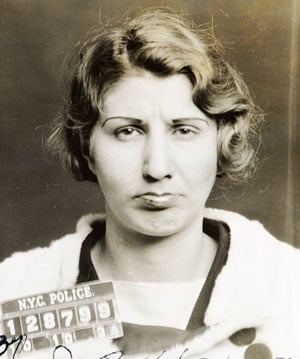

“‘Cokey Flo’ Brown,” Levy explained, although the name meant nothing to Kornbluth. She was a heroin addict and a former madam and an inmate in the Women’s House of Detention awaiting sentence on a prostitution charge. She was also a Dewey witness who’d earlier that day taken the stand and given damaging testimony about a series of supposed meetings between Luciano and his co-defendants David Betillo, Thomas “the Bull” Pennochio and James Frederico—the alleged purveyors of a citywide prostitution racket. Cokey Flo, Levy told Kornbluth, had worked for and lived with Calvit until her arrest two weeks earlier, on May 8, 1936.

Luciano insisted Cokey Flo was a liar. Would Kornbluth be willing to meet with Cantor at the Waldorf-Astoria and then, once briefed on the particulars, pay a visit to Calvit? Tonight, before court reconvened on Saturday morning? Of course, Levy assured him, he’d be compensated for his time.

They agreed on a fee of $100.

FINGERED FOR FAME

Thomas E. Dewey had himself received, just one year earlier, an equally portentous telephone call, from New York Gov. Herbert H. Lehman.

Since the heyday of Prohibition, labor and industrial racketeers had been siphoning an estimated half-billion dollars annually from a New York economy now crippled by the Great Depression. Corrupt or ineffectual Tammany Hall leaders like Mayor Jimmy Walker and District Attorney Thomas Crain had become targets for good-government reformers like Samuel Seabury and Fiorello La Guardia, and Lehman had bent to the reformist tailwinds by calling an extraordinary term of the New York Supreme Court to tackle the twin scourges of organized crime and public corruption in New York County.

Herbert H. Lehman. Getty Images.

To head off accusations of a whitewash, Democrat Lehman had appointed Philip J. McCook, a crusty Republican jurist and close confidant of La Guardia’s, to preside over the special session. Now Lehman needed a vigorous courtroom advocate—and preferably a Republican—to act as his special prosecutor.

Would Dewey, age 34, the mustachioed “baby prosecutor” who’d once garnered headlines by convicting bootlegger Irving “Waxey Gordon” Wexler of income tax fraud, answer the call?

The only child of a fiercely partisan Michigan newspaper editor who’d announced his son’s birth by reporting that a “10-pound Republican voter was born last evening to Mr. and Mrs. George M. Dewey,” Tom Dewey attended both the University of Michigan and Columbia Law School, graduating from the latter in 1925. He became an assistant U.S. attorney in 1931 and, upon his mentor George Z. Medalie’s resignation in November of 1933, the youngest acting United States attorney in the history of the Southern District of New York.

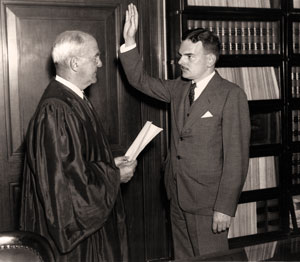

Judge Philip McCook swears Dewey in as special prosecutor in 1935. AP Photo.

Dewey’s appointment by Gov. Lehman as special prosecutor in June of 1935 represented a welcome return to the public eye for a restless Wall Street lawyer intent on fulfilling his father’s ambition by launching a career in Republican politics. But for Dewey and his hand-picked score of assistant district attorneys, the pressure to deliver results was immediate, and the veil of secrecy that seemed to enshroud Lucky Luciano doubly frustrating. So when rumors swirled that a new “downtown bonding combination,” spearheaded by Betillo and Pennochio, was seeking to organize the previously freelance world of New York prostitution, Dewey sprang into action.

On Feb. 1, 1936, at precisely 9 o’clock on a Saturday evening, 160 uniformed officers descended on 80 known disorderly houses in New York City, arresting 87 prostitutes and madams. Then on April 1, New York detectives dispatched to the mob playground of Hot Springs, Arkansas, and arrested a vacationing Luciano, igniting a pitched extradition battle that culminated in a raid on the Hot Springs jailhouse by 20 Arkansas state troopers. By the time the smoke cleared on April 19, Luciano was back in Manhattan, where his bail was set by McCook at a whopping $350,000—$6 million in today’s dollars—the highest in New York history.

All that remained now was for Dewey to prove his extraordinary claim that Luciano, the richest and most powerful gangster in America, was skimming nickels off of two-dollar prostitutes.

Dewey, the youngest U.S. attorney in the Southern District, was once dubbed the “baby prosecutor.” AP Photo.

THINK QUICK

George Morton Levy had also received a telephone call—this on a Friday afternoon in May of 1936 from Moses Polakoff, Luciano’s longtime attorney. Would Levy be willing to defend the alleged mob kingpin known as Charlie Lucky against 90 counts of compulsory prostitution?

“How much time would I have to prepare?” Levy asked, to which Polakoff replied: “The trial starts on Monday.”

Levy, then 48, was no stranger to seat-of-the-pants lawyering. He’d tried his first capital case at age 26, defending Florence Carman, the jealous wife of Dr. Edwin Carman, whose patient, Lulu Bailey, had been shot dead in the doctor’s examining room. For the first Carman trial—a hung jury—over 3,000 spectators had crowded the Mineola courthouse vying for 300 seats, making it New York’s hottest judicial attraction since the Harry Thaw trial of 1908. And when defense attorney John J. Graham fell ill on the eve of the scheduled retrial, it was young Levy who’d moved from the back bench into the first chair and thence, with the stunning defense verdict, onto the short list of every accused New Yorker in need of a courtroom champion.

While Levy had handled his share of high-profile cases in the two decades following, undertaking to represent a man like Luciano in one of the most ballyhooed trials of the 20th century was no trifling matter. It was, in fact, a life-altering proposition. Until then, Levy had been known as a charismatic barrister from Long Island and a walking textbook on criminal law and procedure. Should he take the Luciano case, he’d henceforth be called a mob lawyer—a mouthpiece. That label would follow him into every courtroom, every client meeting and every social function he’d ever attend. It would, he envisioned, be the lead item in his obituary.

And then there were the practical hurdles that Polakoff had outlined. Dewey, the special prosecutor, had run hundreds of witnesses through two specially convened grand juries, all with the avowed goal of convicting the man he’d publicly labeled “the greatest gangster in America.” He’d arrested over 80 prostitutes as material witnesses and held them under threat of prosecution for nearly four months while persuading them, one by one, to give state’s evidence. He had a small army of lawyers, accountants and police detectives at his beck and call, as well as a judge in his corner whom Polakoff described as more co-prosecutor than neutral referee.

Dewey had even enlisted the state legislature to tip the scales in his favor. Never before in New York history had multiple crimes against multiple defendants been combined into a single indictment. But thanks to a new statute passed at Dewey’s behest, the so-called joinder law, Luciano would sit in the dock alongside a dozen pimps and street thugs, there to be spattered by whatever filth the prostitutes might hurl in their direction. And to cap matters off, it would be a trial by ambush with no foreknowledge as to whom the witnesses would be, let alone what they might have been coached or coerced into saying.

Those were the downsides. Levy, on the other hand, had made his reputation by backing the long shot. He believed that every accused, no matter how unsavory his reputation or heinous the crime alleged, was entitled to his day in court, where he stood innocent until proven guilty. To the shopkeeper’s son from Freeport, these were neither hollow bromides nor hackneyed clichés, but rather the twin pillars upon which stood the greatest system of criminal justice the world had ever known.

George Levy had played against stacked decks before, and he’d usually managed to turn the final ace.

A NO-ACCOUNT DAME

Kornbluth met Levy on Saturday morning and, once they’d settled into their taxi, informed him that Calvit had no useful information to impart. Yes, she’d hired a live-in typist in February to assist with a book she was writing, but she’d known that girl as Mildred Nelson. Miss Nelson had admitted to Calvit that she’d been sweethearts with one of Luciano’s co-defendants and on one occasion had commented on a newspaper article reporting Luciano’s arrest, stating that the accompanying photograph “didn’t look like Lucky.”

Dorothy Russell Calvit, daughter of stage legend Lillian Russell, was stunned to learn her live-in typist was “Cokey Flo” Brown. AP Images.

“Do you know him?” Calvit had asked her.

“Oh, I’ve seen him. But he doesn’t look like this picture.”

When Nelson was later arrested for solicitation, she’d written from jail and asked Calvit to testify on her behalf. Calvit had done so, but to no avail, and now was horrified to learn that her name had come up in the Luciano vice trial.

The taxi had reached the courthouse. Levy grudgingly agreed with Kornbluth’s assessment—Calvit’s testimony would be of no benefit to Luciano’s defense.

On Monday, May 25, two days after his taxi ride with Levy, Kornbluth took to bed with an ulcerated stomach that had been troubling him for the past several weeks. At 3:30 on Tuesday afternoon, still bed-ridden, he telephoned his office for messages and was told that a prospective client, a Mr. O’Connell, had been waiting for hours to see him regarding an important new case. When Kornbluth demurred, O’Connell came on the line to say that the matter could neither wait nor be entrusted to other lawyers in the office. Again Kornbluth begged off, stating that the earliest he might possibly meet with O’Connell would be the following day.

“Cokey Flo” Brown, aka Mildred Nelson. AP Images.

A half-hour later, Kornbluth had a visitor. O’Connell, subpoena in hand, now identified himself as a police detective assigned to the staff of special prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey with instructions to take Kornbluth into custody. When Kornbluth protested, O’Connell summoned Thurston Greene, one of Dewey’s assistant district attorneys, to Kornbluth’s apartment. Under hostile questioning by Greene, Kornbluth related verbatim his conversations with Dorothy Russell Calvit and George Morton Levy.

“Isn’t it a fact that Levy and Cantor told you to get Mrs. Calvit to testify that Cokey Flo didn’t know Luciano?” Greene demanded, which Kornbluth vehemently denied.

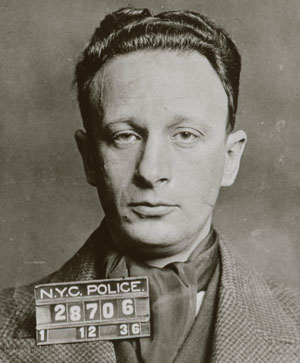

An ambulance was summoned, and Kornbluth was transport-ed first to the Empire Boulevard station house, then to Dewey headquarters on the 14th floor of the Woolworth Building and finally to McCook’s apartment at 57th Street and First Avenue, where, at 10:30 p.m. and without notice to the defense, the judge arraigned Kornbluth on a charge of attempted subornation of perjury. The hapless lawyer was taken to police headquarters at Grand and Centre streets, where he was booked, fingerprinted and transported to city prison.

The next day’s banner headline in the evening edition of the New York Post screamed LAWYER HELD AS VICE RING PLOTTER and Samuel Kornbluth, an attorney of 25 years’ standing with an otherwise impeccable reputation, saw his life and his livelihood ruined.

It was also in that moment that George Morton Levy realized the magnitude of what he was up against.

HIGH IDEALS

Charles “Lucky” Luciano was born Salvatore Lucania in the Sicilian mining town of Lercara Friddi on Nov. 24, 1897. He immigrated to America at age 9 along with his mother and two siblings, joining his father, Antonino, and his older brother, Bartolo, in a tenement flat on East 13th Street, then a predominantly Jewish section of Manhattan’s teeming East Village. It wasn’t long before Salvatore, speaking virtually no English, decided that life on the streets held greater fascination—and greater promise—than whatever it was they were trying to teach him in public school.

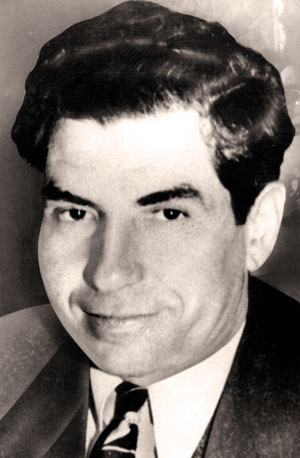

Luciano was born in Sicily. AP Images

It was during his teenage years as a dropout, dope dealer and petty extortionist that Salvatore—who’d by then Americanized his name to Charlie—fell in with a ragtag crew of like-minded toughs who would remain his pals, and his business associates, for the rest of his working life. Francesco Castiglia, an older boy, was a mentor. Little Maier Suchowljansky and his younger friend Benny were acolytes. But it wasn’t until 1920, when the Volstead Act went into effect, that Frank Costello, Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel and Lucky Luciano put aside their small-time rackets and devoted their nascent talents to the high-stakes business of bootlegging.

Passage of the 18th Amendment had spawned a boisterous era of bathtub gin and midnight speedboats, of armed truck convoys and blazing turf battles. Speakeasies opened in every American town—including over a thousand in New York City alone—as the nation awoke with a roar from its postwar doldrums. Americans wanted their booze, and the vacuum created by Prohibition was quickly filled by big-money players like Arnold Rothstein in New York, Waxey Gordon in Philadelphia and Nucky Johnson in Atlantic City.

Thanks to its roots in both the Italian and Jewish demimondes, Lucky’s so-called Broadway Mob, whose membership had grown to include the likes of Giuseppe “Joe Adonis” Doto and Vito Genovese, gained a toehold in New York’s burgeoning bootlegging scene, and Lucky himself soon fell under the protective wing of Sicilian mob kingpin Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria. But when a power struggle between Masseria and chief rival Salvatore Maranzano escalated into the bloody and protracted Castellammarese War of 1930-31, causing everyone’s business to suffer, a disaffected group of younger “Americanized” gangsters—both Italian and Jewish—turned to Lucky for leadership.

On April 15, 1931, as Masseria and Luciano played cards at Nuova Villa Tammaro in Coney Island, four gunmen alleged to be Siegel, Genovese, Doto and Albert Anastasia entered the restaurant with guns blazing. It was Lucky’s bloody betrayal of Joe the Boss that ended the Castellammarese War and installed Maranzano as the new and undisputed head of the Italian underworld.

A former seminary student in his native Sicily, Maranzano had a lifelong fascination with Roman history that inspired him to reorganize his new empire along the lines of Caesar’s Roman legion—decini led by a capo, with each capodecina reporting to a sottocapo. There were to be five New York capo famiglia, headed respectively by Maranzano (today’s Bonanno crime family), Luciano (Genovese family), Tom Gagliano (Lucchese family), Joe Profaci (Colombo family) and Frank Scalise (Gambino family), with Maranzano acting as capo di tutti capi, the first among equals.

The body of Salvatore Maranzano, after Luciano sent assassins to his office on the ninth floor of the New York Central Building, overlooking Grand Central Terminal. AP Images.

Although Maranzano’s organizational influence over the American mafia would prove enduring, his actual tenure as Boss of Bosses was short-lived. Lucky, upon hearing rumors of a Maranzano contract on his life, struck first on Sept. 10, 1931, when four knife-wielding assassins posing as revenue agents cornered Maranzano in his ninth-floor office in the New York Central Building—a fitting end for a man who would be Caesar.

Having engineered the murders of Masseria and Maranzano, Lucky now stood to assume leadership of New York’s Five Families. Except that Lucky, who’d chafed under the imperious rule of the old-world “Mustache Petes,” had a better idea. He proposed creating a national crime commission—a governing board of top mobsters that would vote on matters of mutual interest and concern. It was this cooperative, democratic and multiethnic model of underworld governance that would cement the mob’s social and political influence and inspire historians to label Lucky Luciano “the man who organized crime in America.”

Still in his mid-30s, Lucky lived like the successful executive he was, presiding over the commission’s affairs from his suite at the Waldorf Towers or his private box at Saratoga Race Course. Even the end of Prohibition failed to cramp Lucky’s style because he and his Broadway Mob had already diversified into gambling, drugs, industrial racketeering and dozens of other illicit ventures—all operating under the protection of New York’s Tammany Hall political machine. Despite his new wealth and status, Lucky was careful to maintain a low public profile while letting gangsters such as Al Capone and Dutch Schultz grab the headlines and attract the unwanted attention of law enforcement.

Some events, however, proved beyond even Lucky’s control, and one of them—the Great Depression—wrought a sea change in New York politics, leading eventually to Dewey’s appointment as special prosecutor.

After his extradition from Hot Springs, Arkansas, Luciano (center, light suit) would no longer be a stranger to New York courtrooms. N.Y. Dept. of Records; Library of Congress.

SPECTACLE ON CENTRE STREET

The trial of People v. Luciano began on May 11, 1936, and lasted nearly a month. Policemen with machine guns and tear gas canisters guarded the corridors of the Centre Street courthouse, while snipers perched on the adjoining rooftops. In all, 68 witnesses testified for the prosecution: a Runyonesque cast of pimps and hookers, cops and hoodlums whose lurid tales of vandalized houses and beaten madams left little doubt as to the guilt of Luciano’s 12 co-defendants. By the trial’s midpoint, however, only one witness had been willing to take the stand against Luciano, and that witness had blown up in Dewey’s face.

Joe Bendix was a serial hotel thief who, after his eighth burglary conviction, was about to begin a prison sentence of 15 years to life. Bendix claimed to have known Luciano for more than seven years, having first been introduced to him by a man named Captain Dutton, and to have been personally hired by Lucky as a collector for the bonding combination—a job he admits he never performed. But Bendix was shredded by Levy on cross-examination, then impeached in myriad ways by subsequent witnesses and events.

The first impeachment came from Captain George Paul Dutton, the man in charge of regulating nightclubs for the New York State Police. Dutton testified that he’d never met Bendix in his life, but that he did know Bendix’s third wife, a showgirl named Joy Dixon, which might explain why Bendix had invoked his name.

The Broadway Mob

Boyhood pals from New York’s Lower East Side, gangsters Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, Frank Costello, Giuseppe Doto and Vito Genovese made their fortunes during Prohibition thanks to the financial backing of gambler Arnold “the Big Bankroll” Rothstein. After his death in 1928 and the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, their so-called Broadway Mob expanded into gambling, narcotics and industrial racketeering while Luciano worked to organize and coordinate the nation’s competing criminal syndicates. AP Images.

The second impeachment came from Dixon herself, whom Bendix claimed had been present at the Villanova Restaurant for his job interview with Luciano. Dixon not only denied having attended any such meeting but proved by her own passport that she’d been out of the country at the time.

The final nail in the testimonial coffin of Joe Bendix came when a letter he’d written to Dixon from the Tombs prison was mistakenly delivered to the office of Morris Panger, the assistant district attorney with whom Bendix was also negotiating for clemency. In that letter, Bendix stressed the importance of gaining Dewey’s cooperation and urged his wife to “think up some real clever story” to tell the prosecution. Worse yet for Dewey, it was shown that he’d had the Bendix letter in his possession for over a week before Panger brought it to the attention of the defense.

With his case against Luciano foundering, Dewey desperately needed an eyewitness willing to place Lucky in the company of his alleged co-conspirators. He found that witness during the trial’s second week when Cokey Flo Brown, the former grifter who’d jumped bail on a previous drug arrest and was awaiting sentence on her solicitation conviction, penned a letter to the prosecution from her cell in the Women’s House of Detention.

“Charlie Not-So-Lucky” was first sent to Sing Sing but soon transferred to the Clinton Correctional Facility. AP Images.

Cokey Flo took the stand on May 21, a week after completing her five-day heroin reduction cure. So frail was her condition that McCook allowed her sips of brandy during breaks in her testimony, in which she described five different meetings she claimed to have attended with Luciano, Betillo, Pennochio and Frederico. After nine grueling hours of cross-examination failed to shake her story, Dewey at last had the testimony he’d so badly needed.

Two additional prostitutes, Nancy Presser and Mildred Harris, both also heroin addicts, would ultimately testify against Luciano. Presser claimed to have visited Lucky professionally at both the Barbizon-Plaza and the Waldorf, but she was eviscerated by Levy on cross-examination when she was unable to describe Lucky’s hotel rooms—even, for example, whether they had twin or double beds. Harris was impeached by a former boyfriend to whom she’d allegedly admitted that she “didn’t know Lucky from beans” and when an immunity letter she’d denied receiving from the special prosecutor later turned up in evidence.

The prosecution rested on May 29, 1936, after which Luciano, fearing there was enough testimony in the record to support a conviction, ignored Levy’s advice and insisted on taking the stand in his own defense.

Joe Bendix. AP Photo.

The dramatic head-to-head clash between special prosecutor and Mafia overlord occurred on June 2, 1936, and before it was over Dewey established, over Levy’s strenuous objections, that Luciano had been a gunman, a dope peddler, a perjurer and a tax cheat whose telephone records evidenced friendships with notorious gangsters like Louis “Lepke” Buchalter and Ciro “the Artichoke King” Terranova. What Dewey failed to demonstrate, however, was any direct connection between Lucky and the prostitution bonding combination that was the actual subject of the prosecution.

The jury returned its verdict in the wee hours of Sunday morning, June 7, to a courtroom packed with reporters as more than a thousand Luciano supporters held a candlelight vigil in nearby Columbus Park. A straw poll of newsmen who’d covered the trial came out 13 to 1 for acquittal. The jury, however, felt otherwise; and by the time the entire verdict was read, the word guilty had been pronounced 558 times.

Eleven days later, McCook sentenced Luciano to serve 30 to 50 years in state prison, ending—or so he thought—the criminal reign of the man newspapers were now calling Charlie Not-So-Lucky.

As World War II touched the United States, inmate No. 24806 still controlled the New York docks, and he assisted with the war effort. N.Y. Dept. of Records.

THE UPSHOT

The Luciano trial’s aftermath proved no less dramatic, or problematic, than the trial itself. Defense allegations that Dewey had suborned perjury by wining and dining the cooperating prostitutes—by rewarding Nancy Presser with an expense-paid trip to Europe, and by securing for Cokey Flo Brown and Mildred Harris a lucrative film-and-magazine deal—were corroborated when all three women signed sworn affidavits recanting their trial testimony. But the verdict was affirmed on appeal, and the U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari.

Nancy Presser’s testimony won her a free trip to Europe. AP Images

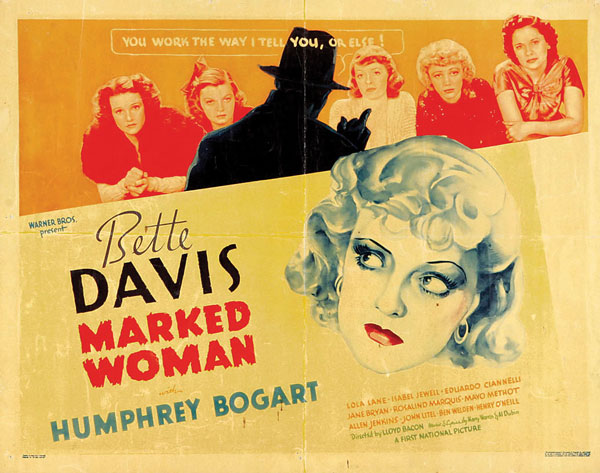

Dewey rode the crime-busting reputation he’d burnished in the Luciano vice case first to the Manhattan district attorney’s office, then to the New York governor’s mansion, then all the way to the front steps of Harry Truman’s White House. Levy, disillusioned by the trial’s outcome, quit the law in 1940 to start a nighttime harness racing venture called Roosevelt Raceway. Cokey Flo, after seeing herself portrayed by Bette Davis in the 1937 film Marked Woman, disappeared into obscurity and addiction in the brothels of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.

As for Lucky Luciano, the final chapter of his life remained to be written. America’s entry into World War II made the safety and efficiency of the Atlantic waterfront a national priority, and inmate No. 24806 of the Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora still controlled the New York docks. For his role in assisting the U.S. war effort, Lucky received a pardon from then-Gov. Dewey after serving only 10 years of his sentence. Deported to Italy as part of the deal, he would briefly reside in Havana, Cuba, from which he—along with boyhood chums Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky—would finance construction of the Flamingo hotel-casino in Las Vegas.

Charlie Luciano died of natural causes in Naples, Italy, on Jan. 26, 1962. Only in death was he finally allowed to return to New York, where his body is interred at St. John Cemetery in Queens, in a family vault labeled Lucania.

Bette Davis portrayed Cokey Flo in 1937. MoviePosterDB.com

This article originally appeared in the November 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Getting Lucky: Spring 2016 marks the 80th anniversary of one of the most colorful & controversial criminal trials in American history.”

A member of the State Bar of California, C. Joseph Greaves is the author of five novels, most recently Tom & Lucky (and George & Cokey Flo).