How Dewey management's rosy picture masked an ugly truth

Illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin

“When we created the firm, we said that our fundamental strategy was to be in the category of elite global law firms,” Davis told this reporter during an interview for a story that appeared in The American Lawyer magazine. “We wanted to be the firm that targeted complicated and challenging work from great clients and was capable of working throughout the globe.”

After the 2007 merger of the highly regarded New York City-based firms Dewey Ballantine and LeBoeuf, Lamb, Greene & McRae, Davis’ primary focus for several years was integration. That changed when 2011 hit, as Davis said he felt it was time to execute part two of his plan to make Dewey into a global law firm behemoth.

During its last year and change of existence, Dewey & LeBoeuf was clearly in expansion mode, having welcomed nearly 40 lateral partners, including well-respected lawyers and BigLaw veterans such as Latin America corporate specialist Michael Fitzgerald of Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy; mergers and acquisitions partner Ilan Nissan of O’Melveny & Myers; and intellectual property litigator Henry Bunsow and antitrust litigator Roxann Henry, both of whom came from Howrey.

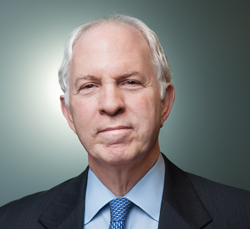

Steven Davis arrives in handcuffs for the arraignment at Manhattan Criminal Court in March 2014. Photo by Reuters Carlo Allegri.

But just one month after the interview, Davis was singing a different tune. During a global partners’ meeting, Davis was widely reported to have revealed that the firm was on the verge of collapse. Those newly acquired lawyers were now back on the market—only this time they were joined by every single one of their partners, counsel, associates, secretaries and other Dewey & LeBoeuf employees. Within six months, references to the firm were in past tense.

Dewey & LeBoeuf wasn’t just history; it had made it, too. When it shuttered its doors in May 2012, it was the largest law firm failure in U.S. history.

Dewey & LeBoeuf presented itself as a thriving global giant. In reality, it was a debt-ridden disaster that tried to buy its way out of trouble. The firm’s greatest piece of capital during its last few years of existence was its sterling reputation, and the firm leveraged that to paint a rosy picture that was accepted by law firm consultants, media professionals, investors, financial institutions, lateral partners and its own lawyers and employees. Davis and others continued to paint that rosy picture of Dewey up until the very end.

One more historical bullet point: Dewey & LeBoeuf became the highest-profile law firm to have some of its leadership criminally charged with grand larceny, securities fraud conspiracy and falsifying business records. At publication time, Davis, executive director Stephen DiCarmine, chief financial officer Joel Sanders and client relations manager Zachary Warren were facing trial for their roles in Dewey’s failure. Davis, DiCarmine and Sanders were scheduled to be tried in Manhattan in February (Warren is scheduled to be tried separately at a later date). If they wish to go free, they’ll have to convince a jury that their relentless positivity was not a cynical ploy but a sincere belief that Dewey’s best days were still ahead.

AP Photo/Richard Drew

WARNING SIGNS

But not all partners viewed the firm through the same halo as Davis and his fellow executives. Catherine McCarthy, an energy partner in the Washington, D.C., office, says she became aware of problems at the firm in the fall of 2011.

An 18-year veteran of LeBoeuf Lamb and then Dewey & LeBoeuf, McCarthy says she became concerned after making trips to the New York office, which seemed more in tune with what was really going on at the firm. By March 2012, she says, she’d be in New York one day and see partners packing up their offices, and then she’d be in D.C., where it was business as usual.

“There was not a lot of transparency about the firm’s financial condition,” she says. “I know that many partners asked a lot of questions about the firm’s accounting in the years leading up to the firm’s demise. They did not always receive complete responses, and the pattern was that the partners would get busy on client matters and not follow through.”

Legal consultant and recruiter Jon Lindsey sensed all was not well at Dewey & LeBoeuf after several partners complained they weren’t receiving promised payments, with some claiming they were being paid less than senior associates. Photo courtesy of Jon Lindsey.

Outside observers also sensed something was up. Jon Lindsey, co-founder of the New York office of Major, Lindsey & Africa, says he knew the firm was in trouble about 18 months before it went out of business. “We kept getting visits from partners who said they had been promised certain amounts of money but weren’t getting it,” he adds. “Some of them said they were even paid less than senior associates. That seemed like a very bad sign to me.”

Nevertheless, the firm continued to sell itself as a great place to be. London-based private equity partner Mark Davis, who joined in May 2011 from Taylor Wessing, says he came aboard because he hoped to join a U.S.-based global firm that would allow him to expand his practice.

“I did some due diligence when I was going through the lateral hiring process, and I did ask about financials,” Davis says. “But there is a limit in any joining process to how many questions you can get to ask.

“But I was joining Dewey & LeBoeuf, a great firm. On the basis of the information I was given, I had no reason to suspect there were any financial issues.”

During the 11 months he was at Dewey, Davis says, he spent most of his time traveling and building up his practice. As such, he had no inkling that the firm was in trouble until that January partners’ meeting.

“I was still quite new and feeling like things were going well,” says Davis, who joined McDermott Will & Emery in April 2012. “I was glad I had made the move—until the partners’ meeting, when it was clear that there were big issues.”

International arbitrator Pieter Bekker also joined Dewey during its last year. Based out of Dewey’s Brussels office as counsel and then a nonequity partner, Bekker says he was recruited by famed arbitrator James Carter, himself a recent lateral to the firm.

“It was very hard to get information about the firm from the Brussels outpost,” Bekker recalls. “No one showed up at the door after the firm collapsed. It was like they simply forgot about Brussels. I just cleared out there and was on the market for five to six months.”

Bekker says he was one of the last lawyers on the payroll because he had to make an oral argument in federal court on behalf of a major client three days after the firm officially dissolved.

“The week before the firm officially closed its doors, I contacted the firm’s management, which was now led by Steve Horvath and Jeff Kessler [and others], and told them I needed to be in court for a major client,” says Bekker, who filed a claim against the bankruptcy estate for approximately $4,000 in travel-related work expenses he says the firm had agreed to pay him but never did.

Bekker recently relocated to the New York City area after his wife got a job there, and he is looking for work. “I didn’t lose any capital contributions or pension funds,” he says, “but my practice has suffered.”

Reuters/Eduardo Munoz

BIG LOSSES

Other partners say they lost significantly more than the $4,000 Bekker says he’s owed from Dewey. Michael Fitzgerald, one of the biggest names to join the firm during its final year, claimed Dewey owed him $38 million in compensation that had been guaranteed when he made the move from Milbank Tweed in July 2011. In February 2013, Fitzgerald filed an objection against the proposed bankruptcy liquidation plan for the firm and demanded his money.

“Fitzgerald was fraudulently induced by members of management of the debtor to leave his prior law firm and join Dewey in July 2011 based on false representations and false promises relating to [Dewey’s] business and financial performance,” Fitzgerald’s attorney, Alan Kolod of Moses & Singer, wrote in his objection.

Fitzgerald claimed that he had negotiated a five-year fixed compensation guarantee, and that Dewey promised to kick in $9 million to make up for forfeited pension payments. Fitzgerald, who is now a partner at Paul Hastings, settled his claim the next month while agreeing to pay $1 million to avoid having to pay out future profits to the bankruptcy estate.

IP litigator Bunsow went even further, filing suit against Davis, DiCarmine, Sanders and others, accusing them of “running a Ponzi scheme in order to enrich themselves and select partners of the firm.” Bunsow, who joined Dewey in January 2011 from failing firm Howrey, claimed in his lawsuit that he’d been guaranteed $5 million a year, and that when he asked about the firm’s finances, Davis, DiCarmine, Sanders and others told him Dewey was in great shape.

Bunsow also claimed he was encouraged to make a $1.8 million capital contribution immediately, and was told by Sanders he could borrow the amount necessary to fund his capital account from Citibank, and that the firm would pay interest on the loan for three years. Bunsow, who started his own firm after leaving Dewey, voluntarily dismissed his case in March 2014.

Other partners apparently took more direct action. Law360 reported in April 2012—almost two years before charges were announced—that a group of partners “asked the New York district attorney to bring criminal charges against the chairman of the tottering firm.”

The four Dewey defendants arrive in handcuffs for their arraignment at Manhattan Criminal Court in March 2014. Photo by Reuters Carlo Allegri.

FATED WALK

The irony couldn’t have been lost on Davis and his three co-defendants as they made their highly publicized perp walk last March through the Manhattan Criminal Court building—once ruled by Thomas Dewey, the former Manhattan district attorney and namesake of Dewey Ballantine.

“Fraud is not an acceptable accounting practice,” said Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. at a press conference announcing the indictment. “Their wrongdoing contributed to the collapse of a prestigious international law firm, which forced thousands of people out of jobs.”

According to the indictment, the firm’s merger, which took place right before the onset of the Great Recession, was troubled from the start. The indictment alleges Dewey & LeBoeuf had been way below its expected financial benchmarks during its first full year of operations in 2008 and was carrying more than $100 million in debt. The firm had several lines of credit in excess of $130 million with various banks, and part of those credit agreements was a covenant requiring Dewey to maintain a minimum year-end cash flow—a covenant the firm could not meet due to poor financial performance.

“The defendants and others at the firm were aware that the failure to meet the cash-flow covenant during the 2008 credit crisis could have disastrous effects on the firm,” the indictment alleges.

The defendants concocted a scheme to defraud the firm’s lenders, the indictment says, by inflating its numbers in order to meet its covenant. Prosecutors further allege the defendants and others continued doing this in subsequent years and lied to their partners and auditors about it.

Law firm consultant Peter Zeughauser recalls being surprised at Dewey’s reported financial performance from the beginning. During its first full year of operations as a merged entity in 2008, Dewey reported just over $1 billion in gross revenue, a 2.1 percent increase from the previous year. Zeughauser notes that newly merged firms usually experience flat growth during the first year because it takes time before they reap the benefits of cross-selling or client-relationship expansion.

Legal recruiter Lindsey also found the numbers odd. “I didn’t look at the numbers and go ‘Oh my God, they must be lying!’ ” recalls Lindsey. “They were hard to believe, but there was no way to tell whether the numbers were legitimate or not.”

In an unusual step, the firm decided to seek $150 million in a private bond offering in 2010. At the time, Zeughauser recalls, he was not suspicious of the move. He even thought it was creative and, if successful, could cause other firms to follow suit. Keith Wetmore, then-chair of Morrison & Foerster, told Bloomberg it was a sign of Dewey’s strength and financial stability, noting that “you need a pretty good balance sheet to interest institutional investors.”

But others were skeptical. Bruce MacEwen, a consultant and president of Adam Smith, Esq., recalls being floored when he viewed Dewey’s prospectus. “It was the most bizarre private placement memo I’ve ever seen,” says MacEwen, who formerly practiced securities litigation. “There was no entry for risk factors in the table of contents—that’s one of the pillars of an offering document. There were, I think, two pages about pro bono work, a couple on diversity. No mention of guarantees to partners. It was more of a marketing document.”

That said, MacEwen notes, it was successful in bringing in investors. “I think the investors were mostly insurance companies,” he says. “What can you say? They bought into it. And they’re big boys.”

Last March, the Securities and Exchange Commission charged Davis, DiCarmine, Sanders, finance director Frank Canellas and controller Tom Mullikin with securities fraud. Mullikin reached a partial settlement with the SEC in September.

At a press conference on March 6, 2014, Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. Announced charges against four former Dewey employees. “Their wrongdoing,” he asserted, “contributed to the collapse of a prestigious international law firm, which forced thousands of people out of jobs.” Photo by Corbis @Bryan Smith.

‘VORACIOUS GREED’

Commentators and lawyers agree the firm’s exploding payroll helped hasten its demise. “I am not sure when we lost our way on compensation matters, but at some point many of the partners started expecting—and receiving—compensation along the lines of senior partners at investment banks or rock stars,” says McCarthy, the energy partner from D.C.

It’s an assessment that Davis, DiCarmine and Sanders share. In their motion to dismiss, the three defendants blamed the “voracious greed of some of the firm’s partners” as a factor in Dewey’s demise.

To some, however, that allegation was laughable: It was Davis who had initiated the use of guaranteed, big-money contracts as a way of recruiting laterals and retaining important partners as well.

“Steve Davis’ big coup was recruiting Ralph Ferrara out of Debevoise” & Plimpton, says MacEwen. “That was a huge success. Maybe that was Steve Davis’ original sin, so to speak.”

Ferrara, a securities litigator and rainmaker, turned heads when he joined LeBoeuf Lamb in 2005. According to The American Lawyer, Ferrara and his group didn’t come cheap. LeBoeuf had to guarantee more than $40 million in salary and pension benefits to close the deal. It was money well-spent, however, given that Ferrara and his group had a book of business worth more than $60 million.

Other big contracts soon followed, to the point that Dewey’s payroll soon resembled that of the New York Yankees. During the 2007 merger, Davis handed a massive guaranteed contract to his counterpart at Dewey Ballantine, firm chair and M&A rainmaker Morton Pierce. According to The New Yorker, Pierce wanted a Ferrara-like deal in order to stay with the newly merged firm, and Davis handed him a deal guaranteeing him about $35 million over five years. The New Yorker also stated that another LeBoeuf bigwig, insurance partner and former LeBoeuf compensation chair Alexander Dye, was given a $3 million annual guarantee to keep him in the fold. Fitzgerald’s mammoth deal was one of the firm’s later guaranteed contracts.

According to bankruptcy court filings, more than one-third of Dewey’s approximately 300 partners had some sort of guaranteed compensation agreement. Consultants acknowledge that having short-term guarantees when partners join the firm is common and beneficial. Many of Dewey’s guarantees, however, fell into the long-term, big-money category.

“When you do the math, it would take an extraordinary performance, year in and year out, in order to honor all those guarantees,” Zeughauser says. “It should be clear to most reasonably intelligent people that those guarantees could not be honored. You can’t make that many guarantees, especially when your performance is declining.”

MacEwen agrees, noting that guarantees can have a destabilizing effect on a firm. “The partners that don’t have guarantees then feel like chumps,” he says. “That’s incredibly corrosive to morale.”

McCarthy points out that several Dewey partners continued to land huge guarantees even as they escaped from the failing firm. “We heard about our Dewey partners landing at firms where they were going to be paid $5 million per year and up as a lateral,” McCarthy says. “I eliminated those particular firms from my list.” McCarthy ultimately moved to Bracewell & Giuliani in May 2012.

In his December 2011 interview, Davis backed the use of guarantees to attract laterals. “It’s pretty hard to bring in laterals without providing some period of guarantee or assurance,” he said. “Some firms don’t do it and I’m totaled by that. My perception is that it’s very hard to get someone, especially of the quality we’re shooting for, to move without providing some base level of assurance.”

Bruce MacEwen, a consultant and president of Adam Smith, Esq., was immediately skeptical: “It was the most bizarre private placement memo I’ve ever seen.” Photo courtesy of Bruce MacEwen.

‘NOT OUR BANKRUPTCY’

‘Not Our Bankruptcy’ Usually when three law firm executives meet with top attorneys from competing firms, a young federal law clerk, and several younger associates, it’s at a bar association meeting, a country club or a cocktail party.

On Nov. 7, all were crammed into a courtroom in Manhattan Supreme Court. The purpose was to try to get the charges against all four Dewey defendants thrown out. Defendant Warren, who had been the firm’s client relations manager, was also trying to get his case severed from the other three. Even he didn’t want to be associated with Dewey’s ex-brain trust. Judge Robert Stolz granted Warren’s motion to sever, but kept most of the charges intact against all four defendants.

“It ain’t over until it’s over, but this was a very good day for the defense,” said Warren’s lead attorney, Paul Shechtman of Zuckerman Spaeder, in a statement after the November hearing.

The defendants have had a giant target on their backs since April 2012, when the group of unnamed Dewey partners met with DA Vance and suggested he look into what was going on at the firm. Vance’s investigation uncovered a trove of emails between the defendants, and he filed some of the more salacious ones with the indictment. The prosecutors allege the emails clearly show the defendants resorting to all sorts of phony bookkeeping, including backdating checks, classifying partners’ capital contributions as payment of legal fees and hiding write-offs.

“I’m really sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but I had a collections meeting today and we can’t make our target,” Sanders allegedly wrote to Davis and DiCarmine. “The reality is we will miss our net income covenant by $100M.” Sanders allegedly claimed he might be able to adjust the books so that the firm only missed by $50 million or $60 million instead.

Vance has taken guilty pleas from seven Dewey financial officials. In his plea agreement, finance director Canellas said he had worked closely with Sanders and at the behest of Davis and DiCarmine in making the illegal adjustments so that Dewey would be able to meet its cash-flow covenants.

“I knew that the firm’s unaudited, and eventually audited, financial statements were false and were being provided to the firm’s lenders, to leasing companies with whom the firm did business, and to others,” Canellas said in his plea agreement. According to the agreement, in return for his full cooperation, the DA’s office agreed to recommend a prison sentence of two to six years for pleading guilty to second-degree grand larceny. Without an agreement, Canellas would have faced five to 15 years in jail.

Davis’ attorney, Elkan Abramowitz, a partner at Morvillo Abramowitz Grand Iason & Anello, did not respond to a request for comment. Neither did Hughes Hubbard & Reed partner Edward Little, who represents Sanders. Bryan Cave partner Austin Campriello, who represents DiCarmine, also declined to comment.

What’s clear from their court filings is that Davis, DiCarmine and Sanders (who filed jointly) intend to argue that they lacked the requisite criminal intent because they fervently believed that the firm would eventually make good on its debts.

They point out that the first principal payment on the private placement bonds was not due until April 2013—nearly a year after the firm went bankrupt. They blamed the DA’s office for torpedoing “an impending merger with another law firm” that destroyed any possibility that Dewey would make its initial payment. According to news reports, Dewey held serious discussions with Greenberg Traurig and what were then Patton Boggs and SNR Denton about possible mergers, but those talks fell apart.

“These defendants did not take the firm into bankruptcy causing it to default,” wrote the attorneys for Davis, DiCarmine and Sanders in their motion to dismiss. “Others made that decision after these defendants were relieved of any authority at the firm.”

In March 2012, Davis was relieved of his sole authority and subsequent decisions were made by a five-partner committee that included himself and four other Dewey partners.

“There could have been no evidence before the grand jury that when [Dewey & LeBoeuf] obtained the money via the private placement, any of these three defendants intended that the money would not be repaid with interest when due,” wrote the attorneys for Davis, DiCarmine and Sanders in their motion to dismiss.

Warren, through attorney Shechtman, said in court filings that he was not involved in any of the alleged transactions and was merely present for some of the discussions relating to the financial adjustments in question. Warren’s defense team also accused the DA’s office of pursuing a personal vendetta, claiming in court filings that the prosecutors had it out for him because they believed Warren had lied when he met with them in Washington, D.C.

“There seems little doubt that the ADAs assigned to this case have come not to like Mr. Warren,” Warren’s attorneys wrote in their August motion to dismiss. “Perhaps it is because he refused to accede to their wishes when they interviewed him.”

Shechtman also wondered how it was possible for a 23-year-old to have brought down such a venerated firm. “What evidence was presented to the grand jury that Mr. Warren, fresh out of college and with no accounting training or experience, knew that the arcane accounting adjustments at issue here were improper or were made with an intent to defraud?”

Consultant Peter Zeughauser recalls being surprised that Dewey & LeBoeuf reported more than $1 billion in gross revenues in the first year of operations after the merger of Dewey Ballantine and LeBoeuf Lamb, noting that merged entities typically experience flat revenues. Photo courtesy of the Zeughauser Group.

PICKING UP THE PIECES

Arbitrator Bekker was hardly the only one to experience a career setback as a result of Dewey. While almost all of its equity partners quickly found new jobs, many associates and support staffers have had a difficult time finding employment.

“In Washington, my understanding is that every last person in the office [attorneys and staff] found other positions,” says McCarthy. “I know that was not the case in our New York office.”

McCarthy says many partners tried to bring as many people with them as possible, but sometimes it wasn’t possible: “Our head legal recruiter in New York, Lauren Rasmus [an attorney now at Morgan Stanley], worked for many, many weeks to make sure that the students who planned to join our firm the summer of 2012 were placed at other firms. Other administrative employees who were similarly situated left as soon as things started to get tough, but Lauren stayed to help the students.”

Even with the benefit of hindsight, most former Dewey partners and law firm experts the ABA Journal spoke with are shocked about the indictments. “I was embarrassed that I had been a partner of a firm that managed its own business affairs so poorly, but I did not believe that there would be criminal allegations against anyone at the firm,” says McCarthy, who stresses that Davis and DiCarmine did a lot of good things at Dewey, such as increase diversity and emphasize pro bono work. “I thought our issues had to do with mismanagement, mistakes and some bad luck,” such as the recession starting just as Dewey Ballantine and LeBoeuf merged.

MacEwen and Zeughauser say they didn’t think criminal charges would be filed, at first. “When the still unnamed partners went to [the Manhattan district attorney], then that’s when things changed for me,” MacEwen says. “I thought, ‘These guys presumably know things that we don’t. They must think there’s something there.’ “

MacEwen says the defendants should have a hard time proving they were merely mistaken. “Almost all firms are run on a cash basis, and it’s hard to run a business like that and have the reported numbers be that far off from the actual numbers,” he says.

Zeughauser agrees, noting that “giving misleading numbers to lenders is a serious offense because you have to attest to the truth of those statements.”

Lindsey notes the allegations against Dewey, if true, are unprecedented. “Other big firms that have gone under in recent years have had business issues,” he says. “Howrey and Heller Ehrman had some big cases end at the same time and some other events that they tried to stop but couldn’t. Thacher Proffitt & Wood was hurt when the bottom fell out of the structured finance market—there was nothing they could do about that. “There are other reasons for law firm collapses, like bad leases or poor performance,” he says, adding, “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Dewey’s Judgment Day: As the legal giant disintegrated, its leaders continued to sell how great things were.”