How countries are successfully using the law to get looted cultural treasures back

Photo of one of the Kneeling Attendants courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons.

For two decades, a pair of monumental statues guarded the entrance to the Southeast Asian galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. These days, all that remains of them are two faint patches on the floor where they stood until a year ago.

On May 20, 2013, the millennium-old statues, known as the Kneeling Attendants, disappeared. They were gently wrapped, crated and moved to a backroom so they could be returned to Cambodia, their country of origin.

The Kneeling Attendants date back to the 10th century, the heyday of Cambodia’s Khmer empire. They were part of a temple complex called Koh Ker. In the early 1970s, when Cambodia became engulfed in a turbulent civil war, looting was rampant, and Cambodia’s rich collection of temples was robbed of statuary and other valuable examples of the Khmer empire’s cultural heritage.

The Kneeling Attendants were cleaved neatly along the feet to separate them from their base before disappearing into the murky shadow world of smuggled art. Eventually they surfaced at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, cut into four pieces.

When the statues arrived in the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the question of provenance was an afterthought. Moreover, Cambodia—still struggling to recover from its civil war and political instability—was unlikely to press a case over the antiquities.

But Cambodia and other war-torn nations have come to recognize that large portions of their cultural heritage have been lost to looters and disreputable art dealers, and they have begun to publicize the losses in a concerted effort to get these antiquities—and their cultural heritage—back. Museums, facing a spate of bad publicity and recognizing their role in protecting cultural heritage, have begun to tighten up internal policies regarding provenance.

Over the past few years, the Cambodian government, with the aid of UNESCO and a range of researchers and archaeologists, has been on a mission to retrieve the looted statues of Koh Ker’s Praset Chen temple.

When officials from Cambodia approached the Met in June 2012 with reams of evidence in its favor, there was little argument to be had. The Cambodian government also secured the return or the promise of return of Koh Ker statues from the Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction houses and the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California, while several other American museums are investigating the provenance of their own Koh Ker statues.

“What we went on was the evidence that there was the physical remains of these objects on the site of the bases from which they had been separated at some point,” says John Guy, the curator in charge of the Met’s Southeast Asian collection. “That in itself was disturbing for us. And that led us to research this more thoroughly and reach the decision we reached.”

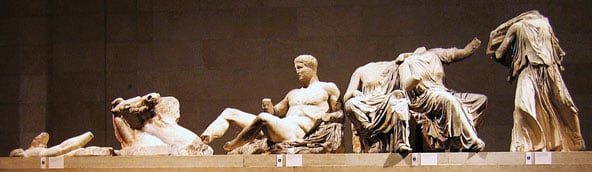

During the brief period (928-944 A.D.) when Koh Ker was the capital of the Khmer empire in Cambodia, many exceptional carvings were produced, including the Kneeling Attendants, seen here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The carvings were repatriated last year. Photo courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons.

A WARM WELCOME HOME

On June 11, 2013, the Kneeling Attendants received an ecstatic greeting upon arrival in Phnom Penh, where they went on temporary display a few days later. In a dramatic scene, the statues were lowered to the tarmac as the tropical night was falling and the front of their crates opened for all to see. High-ranking government officials and Buddhist monks kneeled in front of the statues and offered a blessing. Days later, Prime Minister Hun Sen—Cambodia’s controversial strong-arm leader—was photographed placing a jasmine garland around the neck of one of the statues and kissing it.

Since then, Cambodia has succeeded in getting other Praset Chen pieces returned. Late last year Sotheby’s settled a case against it by promising to repatriate a $3 million statue of the fictional Hindu warrior Duryodhana. This year both the Norton Simon Museum and Christie’s announced within days of each other that each would return Koh Ker statues.

The return of the Cambodian antiquities mirrors an ongoing shift among American and European arts institutions. But it has hardly been a smooth transition, and repatriations are rarely settled as neatly as was the return of the Kneeling Attendants. In May, for instance, the Cleveland Museum of Art announced that an investigation by one of its curators concluded that an ancient statue in its collection did not come from a temple in the Koh Ker complex, as Cambodian officials had alleged. Cambodian officials did not immediately comment on the finding.

“The museum profession and the whole sort of attitude toward collecting shifted over time,” Guy says. “The same expectations and assumptions don’t operate in one generation that operated in the previous generation. All of these factors come into play in something like this.”

The Met’s move represents an about-face even for itself. For decades the museum resisted returning the Euphronios Krater, a 2,500-year-old Greek vase looted from a Roman tomb. In 2006, 25 years after the museum acquired the piece, it negotiated a deal to return it and other items to Italy in exchange for art loans and Italy’s waiving the right to pursue legal action.

Laws governing cultural heritage didn’t begin coming into existence until the second half of the 20th century. Instead, arts institutions quietly carried out dealings with the illicit art market, and curators were far more focused on making a name for themselves and their collection than the ethical and legal implications of such practices. If pressed—even to this day—some directors might argue that culture belongs to the entire world, or that host country institutions are in a far better position to care for works than those of their home countries.

Cambodia’s rich complex of ancient temples held priceless examples of its cultural heritage. Left largely unguarded during a period of civil unrest, they were ransacked and the artifacts were sold to foreign collectors and arts institutions, some of which showed little concern about their provenance. AP Images/Aragami

SHIFTING PUBLIC OPINION

As countries of origin grew savvier about seeking the return of their looted artworks, public opinion began shifting from seeing arts institutions as protective to unduly possessive—unfairly holding on to works to which they had no right.

Tess Davis, an archaeology and heritage law expert at the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at the University of Glasgow who focuses on the illicit antiquities trade in Southeast Asia, says the recent repatriations represent a changing opinion. “There has been a shift in the way museums treat suspect antiquities, as we see in the behavior of the Metropolitan in New York,” she says. “In the 1980s, when presented with evidence that one of their prized acquisitions had been looted from Turkey, the Met strongly fought repatriation through the courts. But this year, to their credit, the museum voluntarily returned two looted statues to Cambodia without waiting for a lawsuit or court order. I do believe that some—most, I hope—museums have changed because it’s the right thing to do. But even the less moral institutions must realize that dealing with looted art—and especially war booty—is bad for business.”

Increasingly, museums are turning to a collaborative model, inking elaborate deals with countries of origin that ensure cross-cultural cooperation, special exhibitions and other perks to make the loss of an artwork worthwhile. Publicity has doubtless played a role.

A detail of the Elgin Marbles—currently on display at the British Museum in London—which once adorned the Parthenon and other buildings on the Acropolis. They were acquired from the Ottoman Empire in the early 1800s by a British Ambassador. Photo courtesy Wikipedia Creative Commons.

Britain—which has a stringent law forbidding the removal of collections within the British Museum—has faced a barrage of bad press in recent decades over its refusal to repatriate the Elgin Marbles, a group of sculptures that were looted from the Parthenon in Athens in the early 19th century and later sold to the British government. Protests outside the British Museum by incensed Greeks and their supporters occur on occasion and today even the majority of the British population believes they should be returned.

The Met, on the other hand, has seen an unusual outpouring of positive press in response to its decision to repatriate.

“The media response has been very positive,” allows the Met’s Guy. “Often the good stories are not the ones that get picked up, so this has been a very positive experience.”

But it’s been a slow change, heritage experts note. After two decades battling Turkey, which claimed that a statue known as Weary Herakles had been illegally squirreled out of the country, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts repatriated the statue in 2011 and admitted that it had never verified the statue’s provenance.

One of the few museums to employ a full-time provenance expert, the MFA these days puts a weighty emphasis on due diligence. “It is necessary for the MFA not to repeat the mistakes of our past,” wrote the curator of provenance, Victoria Reed, in an article in the spring 2013 DePaul Journal of Art, Technology and Intellectual Property Law.

Ricardo A. St. Hilaire, a sole practitioner in Lebanon, New Hampshire, who practices cultural property and museum law, says that recent moves by the Met and the MFA represent the best efforts made by arts institutions, but that some continue to avoid the greater trend.

“I think there’s been a shift in public attitude. In terms of museums, I’ve seen some move in a positive direction and some not at all,” says St. Hilaire, a past vice-chair of the Art and Cultural Heritage Law Committee of the ABA Section of International Law. “Museums are more alert now to probing where certain objects come from—antiquities, WWII art and the like—I think museums are looking at that,” he says. “There is movement, but there is more to do—across all levels.”

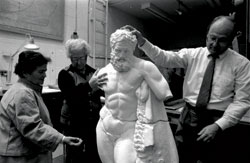

Part ownership of the upper portion of the sculpture known as Weary Herakles was obtained by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts from a German dealer. It was later found to match the lower portion excavated in Turkey, which reclaimed it in 2011. Photo courtesy of Looting Matters.

A LEGAL EVOLUTION

International conventions, laws and enforcement have followed a similar evolution. A 1970 UNESCO convention on the “Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property” gave signatories the ability to seek return of illicitly obtained cultural treasures and set guidelines for collectors. A number of countries began passing their own cultural patrimony laws, some of which verge on the draconian (such as Italy’s, which asserts patrimony rights onto every artwork more than 50 years old and claims the right not just to the antiquity but to any reproduction).

But legislation pertaining to the global pool of antiquities has been spottier. In 1983, the U.S. passed the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act, its own interpretation of how the UNESCO convention should be adhered to. The U.S. measure contains relatively broad powers of interpretation given to a committee of the U.S. Department of State that can decide to what degree other nations’ restrictions on exported cultural property will be followed.

The UNESCO convention and its complementary 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects remain the key frameworks for guiding how institutions and legal bodies around the world address illegal art and antiquities. Countries that are parties to the 1970 convention vow to put in place appropriate laws to combat looting and trafficking, while the later one aims to balance the complexities of the “good-faith buyer” by demanding a level of due diligence.

“Its effect on the art market, which has tended to be reluctant to reveal the origin of cultural objects and where buyers are not unduly curious, will be immediate,” the UNIDROIT Convention notes in its overview.

The implementing statute passed by the U.S. Congress set forth terms for import and export but also regulates how the country judges claims made by other convention signatories. The act established an 11-member cultural property advisory committee in the State Department that reviews requests made by other countries. If the committee determines, for instance, that “the cultural patrimony of the state party is in jeopardy from the pillage of archaeological or ethnological materials of the state party,” it can choose to deny the request.

A second law, the National Stolen Property Act of 1934, also became an important tool in combating illegal cultural heritage trade after the landmark 1974 case out of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at San Francisco, United States v. Hollinshead. After prosecutors successfully used the law to seek conviction of traffickers of pre-Columbian antiquities from Guatemala, the NSPA has been a popular complement in the fight against smugglers.

But while the U.S. legislation makes sense within our judiciary, the country has come under criticism for its role in and response to the UNESCO convention.

“U.S. input during the negotiation for the 1970 UNESCO convention and its subsequent ratification and implementation into domestic law significantly limited the operation of the instrument,” argued heritage law professor Ana Filipa Vrdoljak, in her 2006 book International Law, Museums and the Return of Cultural Objects. “Nonretroactivity was a primary U.S. concern during the 1970 UNESCO convention deliberations.”

Today, even though more than a dozen bilateral agreements prohibiting the import of illicit antiquities have been put into place by the U.S. State Department, they don’t apply retroactively. Anything that has slipped over the borders ahead of the date is fair game, says Todd Swain, an expert on national resource protection who works for the National Park Service.

“I go to a bunch of different countries around the world, and the issue comes up every time. If you go to Guatemala, the Guatemalans will say there’s a bunch of Guatemalan stuff in the U.S. and we want it back. But how can we definitively prove in court that these Mayan pieces are absolutely, positively from Guatemala? And even if we can, how can we show what year they were removed and what law was in effect when they were removed?”

Swain, who has spent more than 20 years as a special agent at the National Park Service investigating and teaching about antiquities and archaeology theft across the globe, says the laws in place in the U.S. make it extremely difficult for home nations to mount a legal battle.

The National Stolen Property Act requires the country seeking return of looted works to prove they had been stolen within its borders, or that they had been taken after the date of whatever relevant provenance law came into effect. The burdensome requirement makes it all but impossible to press a criminal case.

“With antiquities, I could have 10,000 Khmer artifacts in my house and it would be incumbent on someone to prove that they’re ill-gotten. That’s basically impossible to do. I’m sure it’s maddening for these source countries that have been victimized for years. Ethically and morally they should get back their cultural and historical heritage,” he says, “but historically the laws weren’t set up that way.”

“The onus is very much on the origin country; it’s very hard to prove patrimony,” says DePaul University law professor Patty Gerstenblith, a past co-chair of the ABA’s Art and Cultural Heritage Law Committee.

Until the Sotheby’s case was settled out of court in December, the U.S. government was battling it on Cambodia’s behalf. The case, which was extremely rare, highlighted the near impossibility of legally fighting patrimony claims.

“To establish that a cultural object is stolen property, the U.S. would have to show that the country had a national ownership law, that there is enforcement of this law internally within the country, and that the object left the country after the date that law went into effect,” Gerstenblith explains.

“It can look very unfair to a country in Cambodia’s situation. I can see many reasons for saying it should go back, but the U.S. law is what it is. Unless it is changed, I would say both governments would have a very difficult time” proving this case.

A marble sculpture dating to the 4th century B.C. shows a fallen doe being attacked by winged griffins. It was purchased by the Getty Museum in 1985. Years later authorities discovered Polaroid photos at the warehouse of an antiquities middleman, who admitted the sculpture had been looted from Italian ruins. Photo courtesy of Chasing Aphrodite.

THE PRIVATE MARKET

While museums and auction houses remain the focus in disputes over looted antiquities, an even larger problem looms when it comes to the private market.

Every year, thousands of illegal antiquities are smuggled across America’s borders. They come via the postal service or commercial couriers like FedEx. They come hidden, like drugs, inside innocuous objects. They come in crates mislabeled by origin. They come in boxes accompanied by false manifestos.

But in nearly every case, the only thing that happens is an item is voluntarily surrendered and the smugglers walk away scot-free, St. Hilaire says. The customs officials seize the object and file a forfeiture complaint, and the importer chalks it up to the cost of business.

“I wouldn’t change the law. I would change the focus on enforcement. There needs to be an emphasis on true law enforcement,” he adds, “as opposed to just forfeiture cases.”

An increasing pursuit of civil forfeitures (the number approximately doubled from the 1990s to 2000) has been a boon for American diplomacy. The return of thousands of antiquities has earned it plaudits across the globe and served as a much-needed PR boost. But a photo op is hardly a deterrent for smugglers.

“Law enforcement currently focuses on seizing and repatriating looted antiquities, rather than prosecuting those who loot, traffic, sell and buy them,” explains Davis from the University of Glasgow. “This policy has created much goodwill toward the U.S. in countries like Cambodia, which has greatly benefited from the hard work of Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other federal agencies, but it is not adequately deterring the illicit antiquities trade. And thus many in the art market continue to act with impunity.”

“I think the only thing that’s a deterrent is criminal prosecution,” Gerstenblith says. The financial windfall that is the illicit antiquities trade means the occasional loss of an item can simply be considered an operating cost, much like in drug trafficking.

“Some stuff gets lost, but it’s just a bit of overhead given the markup,” Swain says. “On the dollar, the local person gets 50 cents, the runner gets 74 cents, the first importer gets $1.50, next gets $2.50, then it gets to the dealer in the U.S. and they sell for $100. There’s profit being made every stretch of the line and that’s what keeps people in the game.”

“In the U.S., [law enforcement officers] historically go after looters, but it’s the buyers that grow demand. As long as museums will buy antiquities for collections or private collectors will buy them, there will still be people taking the risk.” By Gerstenblith’s estimate, there have been approximately 30 to 40 civil forfeiture cases in the past decade—and perhaps three or four criminal cases.

A Pakistani police officer inspects stolen antiques in Karachi. Reuters/Athar Hussain

A STAGGERING PROBLEM

The biggest cases, however, have been staggering and hint at just how widespread the trade is. New York art dealer Subhash Kapoor was arrested in Germany in 2011 and extradited to India in 2012, where he awaits trial for overseeing a global smuggling ring. Separately, the U.S. government issued a warrant for his arrest in July 2012.

ICE—which carried out a four-year investigation at the request of India—ultimately uncovered nearly $100 million worth of stolen antiquities at his Manhattan gallery and various storage units. A statement issued by ICE about the haul suggested Kapoor was “one of the most prolific commodities smugglers in the world today.” Kapoor’s arrest was followed by the October 2013 arrest of his sister, whom the Manhattan district attorney charged with four counts of criminal possession of stolen property. Sushma Sareen alone is accused of hiding $14.5 million worth of statues while federal authorities carried out their raids.

While the cases move forward, museums across the world have begun to carry out their own investigations into items they have purchased from Kapoor. By the count of Chasing Aphrodite—a website run by a pair of former Los Angeles Times investigative reporters who track looted antiquities—at least 240 objects can be traced to museums such as Australia’s National Gallery, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Kapoor faces trial in Chennai for the looting of temples there, but India is just one area on a list of exploited sites. He is believed to have used his network of smuggling rings to move illicitly procured items from Pakistan and Afghanistan—two countries whose instability have made them ripe for plunder.

Iranian artifacts recovered from Syria are displayed in Baghdad. Reuters/Ceerwan Aziz

The reason Khmer antiquities flooded the market is that a decade of turmoil made them an easy target. Unrest coupled with attractive cultural heritage is a fairly simple key to predict the area from which the next influx of antiquities will emanate.

In addition to Khmer antiquities from war-ravaged Cambodia, collectors during the past few decades have been attracted to Mayan artifacts (from Guatemala), Egyptian artifacts, Iraqi artifacts and antique Balkan coins. Today, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq are among the top contenders for looting.

Davis says that while “cultural heritage has always been a casualty of war,” the commodification of antiquities has made them even more vulnerable to armed conflict.

“War is an expensive business,” she says. “So as long as there is a market for these so-called blood antiquities, there will be a supply. At best, those who purchase such pieces are contributing to the destruction of the world’s cultural heritage. At worst, they may be prolonging conflict by funding, even indirectly, those who wage it.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Looted Beauty: Bolstered by a growing body of international and domestic law, more countries are successfully gaining the return of looted cultural treasures.”

Abby Seiff is an American journalist based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.