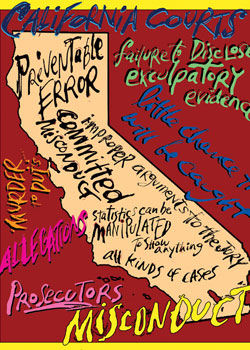

Harmless Error? New Study Claims Prosecutorial Misconduct Is Rampant in California

Illustration by Bernard Maisner

In 1986, a jury in California found Mark Sodersten guilty of beating, sexually assaulting and slicing the throat of a 26-year-old mother of two young children and then setting her body on fire in hopes of destroying the evidence.

The physical evidence linking Sodersten to the crime was scant, but law enforcement had two convincing eyewitnesses: the victim’s 3-year-old daughter and one of the victim’s neighbors.

Two decades later, a state court of appeal vacated Sodersten’s conviction on the grounds that the prosecution failed to provide defense attorneys with four audio recordings of those two witnesses that the judges said could have been a “devastating” impeachment tool and likely would have resulted in a different verdict.

Unfortunately for Sodersten, the court decision came too late. He had died in the California prison system six months earlier.

But Sodersten’s case has resurfaced as Exhibit A in a recently released 113-page report by the Northern California Innocence Project at Santa Clara University School of Law. The report contends that prosecutorial misconduct in the nation’s most populous state continues to be a problem, and that prosecutors are seldom held accountable for misconduct—a charge that prosecutors and the State Bar of California dispute.

The study, titled Preventable Error: A Report on Prosecutorial Misconduct in California: 1997-2009, identified more than 4,000 federal and state criminal cases on appeal in California during the 13-year span in which prosecutorial misconduct was an issue raised by the defense. The report found:

• 707 cases in which courts determined that prosecutors had committed misconduct, such as making improper statements to the jury in closing arguments, improperly coaching witnesses, or failing to disclose exculpatory evidence to the defense.

• 159 cases in which courts found that the level of misconduct was harmful enough to reverse the conviction, declare a mistrial or bar the evidence.

• 67 prosecutors had been found by courts to have committed misconduct more than once, while three prosecutors did it in four cases and two did so in five different cases.

In 282 cases, the court refrained from making a ruling on the prosecutorial misconduct issue, holding instead that any error would have been harmless or that the issue was waived.

The study also found that the State Bar of California took disciplinary action in only six misconduct cases. Three of the six prosecutors were suspended from the practice of law, while two were publicly reprimanded and one was placed on probation.

“Plain and simple, California has a legal system that does not hold prosecutors accountable when they abuse the public trust,” says study co-author Kathleen Ridolfi, a Santa Clara law professor and director of the Northern California Innocence Project. “We have serious problems with prosecutorial misconduct in California and it is not being addressed. These cases are just the tip of the iceberg.”

Ridolfi says that “most prosecutors are doing their job ethically and professionally,” but that some prosecutors commit misconduct repeatedly because they know there is little chance they will be caught and even less that they will be punished, especially because prosecutors have absolute immunity from civil liability. She says prosecutorial misconduct costs tax payers “millions and millions of dollars” to retry these cases, victims are forced to relive the entire experience, and innocent people are sent to prison.

The study found that prosecutorial misconduct occurred in all kinds of cases—from murder trials to DUIs. The two most common forms of misconduct were improper arguments to the jury—making in admissible statements or improperly endorsing the credibility of witnesses—and failure to disclose exculpatory evidence.

“We will never know how many Brady violations there actually were because they are hidden, they are secret,” says journalist and study co-author Maurice Possley. “All we know are the statistics. And we know that without bar disciplinary oversight, it is almost risk-free for the prosecutors.”

The report recommends that prosecutors be required to take increased ethics training, that judges be required to report findings of prosecutorial misconduct to state bar disciplinary officials, and that judges be required in their written opinions to identify by name prosecutors who commit misconduct.

THE PROSECUTION’S DEFENSE

In response, prosecutors and California bar officials claim that the report is flawed, and that it exaggerates the problem.

Scott Thorpe, chief executive officer of the California District Attorneys Association, says actual cases of prosecutorial misconduct are taken very seriously by his organization, but that they are “few and far between.”

“In reality, the time period from which these cases were originally tried dates back to 1980,” he says. “Millions of criminal cases have been prosecuted in California during the past 30 years. That should put the numbers from this study into more perspective. Statistics can be manipulated to show anything.”

Thorpe says the study also fails to recognize the difference in intentional and unintentional error on the part of prosecutors and the severity of the misconduct. He says it is unfair that the report considers simple oversights or mistakes by good and honest lawyers as prosecutorial misconduct.

“There was a reason why the courts ruled in a great majority [548] of the 707 cases that the conduct by the prosecutor was harmless,” he says. “It’s because the error was small and unintentional and did not impact the outcome of the trial. This study simply is not an accurate reflection and unfairly taints all prosecutors for the misdeeds of a very small number.”

In a written response to the study, the State Bar of California said it was reviewing the findings, but it also stressed that its disciplinary counsel takes misconduct by prosecutors seriously.

“Prosecutorial misconduct [as specified in court decisions] does not always equate with attorney mis conduct for disciplinary purposes,” the organization stated. “The state bar believes it is disciplining criminal prosecutors where appropriate, and where the conduct is willful and can be established by clear and convincing evidence.”

Bar officials and prosecutors say there is no better example of the complexities of prosecutorial misconduct claims and flaws in the Northern California Innocence Project study than the report’s own primary example, the Sodersten case.

EXHIBIT A

A California court of appeal posthumously reversed Sodersten’s conviction because of the four audio recordings not turned over to the defense before trial.

The judges pointed most harshly to two tapes made by detectives interviewing the victim’s neighbor and state’s star witness, Lester Williams, who testified at trial he saw Sodersten attack the victim, Julie Wilson, with a frying pan and threaten to kill her. Williams told jurors that Sodersten later told him not to tell anyone what he saw.

But on the tapes, Williams tells the detectives that he made up the entire story about seeing Sodersten attack the victim, and that he was actually on PCP the night of the attack and couldn’t remember anything that happened. Even after the detectives tell Williams that the state would send him to the electric chair for this murder, the witness still insisted he didn’t remember anything about the crime.

Tulare County District Attorney Phillip Cline, who is identified by name in the NCIP report, says neither he nor his investigator knew anything about the existence of those two tapes—a contention that the appeals court acknowledged in its decision.

The other two tapes detail Cline preparing the victim’s then-4-year-old daughter, Nicole, to testify just before the trial. At two or three points on the tapes, Cline appears to coach his young witness on answers and tells her not to let the defense attorney change her mind or confuse her about who she saw “put fire on her mommy.”

But Cline is also heard on the tapes telling the little girl to just tell the truth.

In an interview, Cline swears he turned those two tapes over to defense counsel, who was later disbarred for multiple disciplinary problems not related to this case. Cline says the NCIP never contacted him to hear his side of the story.

“I know in my heart that I turned those tapes over to the defense, but did not have the documentary proof that I did so,” says Cline, who has never been publicly disciplined by the state bar or had other cases reversed due to prosecutorial misconduct. “We were not careful about documenting discovery turnovers back then; we just gave the defense everything we had.”