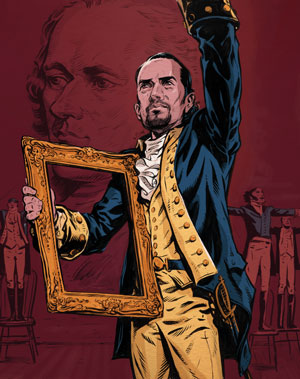

What 'Hamilton' teaches lawyers about framing a story

Illustration by Lars Leetaru

Miranda’s own genius, and what lawyers can most learn from him, is in his fearless adaptations. First, he adapts Chernow’s complex study of Hamilton, chock-full of compelling characters, romance and action too. Second, Miranda adapts oppositional musical forms: the pleasing lyrical Broadway melodies alongside rap’s percussive rhythms, punctuated with explosions of clearly articulated words. Rap’s language is no longer anti-authoritarian or insular. The idiom is not transgressive and the sounds are not assaultive. Rap is now egalitarian and affirmative, matching the romantic American exceptionalism of the show itself.

Miranda also transforms the white, elitist male world of power and privilege built upon a historical shadow world of black slavery, in a society where women were consigned to sexually submissive and proprietary roles. He flips our history upside down to display a multiculturalism and egalitarianism that permits the audience to celebrate an impossibly democratized version of America that our founding fathers, including Hamilton, neither anticipated nor allowed for.

This brings us to Miranda’s final and, perhaps, most ingenious adaptation: his borrowing of selective Hamiltonian ideals. Shards of language and ideals float atop the mix of sampled pieces, especially Hamilton’s federalist vision for a unified country with a strong and centralized federal government. Hamilton’s highly restrictive vision of a limited “representative” democracy is somehow reconciled with the multiculturalism and egalitarianism embodied in the theatrical production of the play.

Miranda’s sampled rap distillations and the transformation of Hamilton’s elitism into an almost-contemporary liberalism become the narrative glue that adheres Hamilton’s heroic biographical story with the formulation of the new nation’s identity.

While reading the closing arguments collected in the excellent Greatest Closing Arguments books by Michael S. Lief and H. Mitchell Caldwell, I realized that trial lawyers, especially in these high-profile closing arguments in historical and spectacular trials, are akin to Miranda in Hamilton. These often theatrical closing arguments “adapt” other stories, sampling from personal anecdotes, and cultural, historical and biblical narratives. Stories-within-stories are nested like Russian dolls, one encased within the form of the next, often framed by a thematic meta-story.

Like Miranda’s Hamilton, the framing story occasionally adapts a political narrative about national identity—who we are as a people. Of course, there is no universally accepted American story about our national identity. For example, in opposition to Hamiltonian blue-state federalism there is the competing red-state Jeffersonian republican counternarrative. It is a political story elevating autonomy and individual freedom as paramount values, while providing a cautionary warning that we must remain ever-vigilant guarding against the monarchial and tyrannical tendencies implicit in a powerful and overreaching federal government.

In American Sphinx, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Joseph Ellis further observes: “The main storyline of American history, in fact, casts Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton in the lead roles in the dramatic contest between the forces of democracy (or liberalism) and the forces of aristocracy (or conservatism). ... It was the people against the elites, the West against the East, the agrarians against industrialists, Democrats against Republicans ... the voice of ‘the many’ holding forth against ‘the few.’ ” This mythologized version of our American foundational political story disserves the complexity of Jefferson’s anti-federalist republicanism, just as Miranda disserves Hamilton’s complex vision. No matter. As the newspaper editor famously observed at the end of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

SPENCE’S STORYLINES

Gerry Spence artfully adapted a mythologized version of the Jeffersonian storyline framing his closing argument on behalf of Randy Weaver, who was indicted for murder, conspiracy and gun charges. The evidentiary trial story was about what happened in the heartbreaking standoff and shootout at Ruby Ridge that resulted in the death of a federal marshal, and the death of Weaver’s wife and young son. Spence’s framing story provided a narrative context that enabled the jurors to understand and empathize with Weaver’s motivations and actions, situating Weaver’s separatist philosophy and fundamentalist religious beliefs squarely within an American Jeffersonian political tradition.

Here is why this framing was crucial: At trial the government had depicted Weaver as the villain in a simple melodrama. He was a heavily armed white supremacist and racist sympathizer of the Aryan Nations, a terrorist complicit in a criminal conspiracy and the murder of a federal marshal.

In his closing argument Spence recharacterized Weaver, who had not testified, as a survivalist, a separatist and a Christian fundamentalist who was not a terroristic villain. Like Miranda, Spence sets his argument in an ahistorical time where past and present merge and historical characters emerge from a mythical past:

“I want to say something to you. ... I want you to realize that few of us, me included, ever really know how important we are or where we stand in history. Go back to 1775 and the Continental Congress. Do you think they thought they were important? They were just local guys doing their job ... but as we look back on history, they did something permanent and magnificent and lasting. Now, one of those fellows, Tom, made a statement. He said, ‘Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.’ You know who Tom is that I am talking about, of course. It’s Thomas Jefferson. ‘Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.’ ”

According to Spence, Weaver is the victim: He is “guilty of being one stubborn mother” and “guilty of being afraid; we are all guilty of that,” but he is not a terrorist. Instead, as the framing goes, it is the corrupt and deceitful federal government that must be stopped by the heroic jury before injustice morphs into tyranny:

“Big Brother has come. The worst of our fears are here, and, thank God, I’m in a courtroom where I can say this with protection. I can point my finger at a government agent in America and say: This man and that agency are the new Gestapo in this country.”

Spence continued: “Now something is very horrid that’s happening here and I want you to hear this. I told you that this is a watershed case and I want you to hear this. What is happening in America when the government begins to point, not to criminals who are joining conspiracies like dope dealers who join up and bankers who do behind-the-scene conspiracies and cheat old ladies out of their savings, but to families? The new low in American jurisprudence is to attack the American family and say that the American family now can be guilty of a conspiracy by virtue of the fact that they are a family.”

The jury, in turn, apparently adapted Spence’s framing story in its own narrative synthesis, and Weaver was acquitted of the murder and conspiracy charges.

STORIES INHABIT SPECIFIC TIME

There are also time-bound reasons why Spence’s Jeffersonian framing story was effective: Weaver’s trial took place in 1993. As Ellis observes, 1992-1993 was the year of the “Jeffersonian surge” in the American popular imagination. Jefferson was virtually everywhere—in movies, on PBS programming and in newspaper headlines (just as Hamilton is today). We were nationally obsessed with revisiting Jefferson’s complex and often contradictory political and personal philosophy. The obsession was provoked, in part, by questions about Jefferson’s personal conduct and by evidence of his sexual relationship with his slave Sally Hemings, a relationship that he repeatedly denied while in office as president. Jefferson’s own presidential hypocrisies and contradictions further reinforce Spence’s theme that “eternal vigilance is the price of freedom.”

Like movies and plays, spectacular and notorious trials are remarkably time-specific. The Ruby Ridge shootings, for example, occurred before domestic terrorism in Oklahoma City and before the 9/11 attacks. I wonder whether Spence’s thematic framing story would work in courtroom theater today. Likewise, how would Miranda’s recasting the life of Hamilton as multicultural assimilationist rap fable have fared in 1992-1993? For that matter, who could have possibly predicted that Donald Trump’s framing story—a retrograde adaptation of an American exceptionalism that excludes and vilifies ethnic minorities—would play so well in the political theater of our own time?

This article originally appeared in the August 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Art of Adaptation: What Hamilton teaches lawyers about framing a story.”

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of Storytelling for Lawyers.