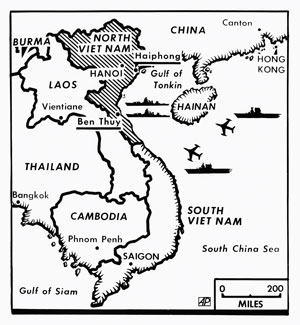

Aug. 10, 1964: Gulf of Tonkin resolution begins the Vietnam War

The USS Maddox. AP photo.

Two days before, the Maddox had repelled an attack by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats dispatched to disrupt the operation. Both sides had minimized the incident, but because of that earlier attack the Maddox was accompanied by another destroyer, the Turner Joy. When several “skunks” (potential threats) appeared to be closing in fast on radar, the group began maneuvers to avoid what seemed to be as many as 13 attacking vessels. By the end of a 94-minute foray with more than 300 rounds fired, the threats seemed dissipated; but questions lingered, even among the commanding officers involved, as to whether what had been seen on radar had been a threat at all.

Relations between the U.S. and North Vietnam had always been complex. The U.S. had continued to support Western interests long after Vietnamese troops defeated the French at the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu. That end of French colonial power in Southeast Asia led to an agreement in Geneva on a temporary bifurcation of the country, north and south, until a reunification referendum could be held in 1956. But that agreement fell prey to the broader Cold War politics that defined similar divisions in the Korean Peninsula and Europe. Rather than accept an inevitable electoral victory for the indigenous Communist faction led by Ho Chi Minh, the U.S. urged repudiation of the Geneva Convention. And by mid-1964, commando raids by a U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government to hector North Vietnamese defensive positions were becoming routine—and the reason for the Desoto patrols.

In that context, the strange, uncorroborated events of Aug. 4 were relayed to President Lyndon B. Johnson through signals intelligence channels as evidence of North Vietnamese aggression. In view of the earlier attack—resulting in the visible destruction of at least two of the North Vietnamese torpedo boats—intelligence supporting a second attack was an easy sell to those inside Congress and the Johnson White House who favored a more aggressive approach to Southeast Asian Communists.

The U.S. naval destroyers Maddox and Turner Joy are shown in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam.

However, an internal NSA analysis approved for release in 2005—including fresh evidence from the North Vietnamese military—showed conclusively that there had been no second attack. Moreover, it showed that intelligence reporting on the Aug. 4 incident had been selective to the point of deception. Even in his own report, the ship’s captain had cautioned that they had “never positively identified a boat as such.” And officers from both destroyers concluded that the suspicious radar returns had been weather spasms and wild surges of water from their own evasive maneuvers.

On Aug. 5, the president reported the action as “a new and grave turn” to tensions in Southeast Asia and asked congressional leaders for a resolution “supporting freedom and … protecting peace” there. On Aug. 7, Congress authorized Johnson “to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force” to assist the non-Communist regimes in Southeast Asia. The resolution, enacted Aug. 10, would not expire until “the peace and security of the area is reasonably assured.” By the next year, the American troop presence in South Vietnam jumped from 23,300 to 184,300, and by 1968 it reached 536,100. By the time peace was “reasonably assured,” more than 1.4 million people, including 58,200 Americans, had lost their lives.

This article originally appeared in the August 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution Begins a War.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.