Michael Lincoln-McCreight remembers the day he was told to go to court. It was 2014, and Lincoln-McCreight, who had recently turned 18 and aged out of the foster care system, was living in a group home for people with intellectual disabilities in Port St. Lucie,

Florida.

Lincoln-McCreight says the situation was fine at first, but then it got weird. “And when I say weird, I mean doctors started coming in and asking me lots of questions, and there was an attorney,” he explains.

Then came the trip to the courthouse.

“Why did I have to go to the courthouse?” he remembers wondering. “I have never been charged with anything, and I wasn’t arrested for anything.”

Lincoln-McCreight is unsure of the details, but a public guardian petitioned the court for plenary, or full, guardianship over his personal and financial affairs.

Guardianship, also called conservatorship, is a term used when state law grants an individual decision-making power over an adult deemed incompetent or a minor child. The court appoints a guardian—typically a family member, a friend or a professional—in conjunction with a finding that the person subject to the guardianship is incapable of acting independently because of age, injury, intellectual or developmental disability or mental health crisis.

A court-appointed guardian’s control is often limitless and can include power over their person and/or property. It includes major decisions such as medical treatments and investment strategies; fundamental freedoms such as the right to vote; and lifestyle choices such as taking a vacation, seeing friends or adopting a pet. Once a legal guardianship relationship has been established, only a judge can adjust or terminate the order.

Lincoln-McCreight says the court hearing was swift, and he wasn’t given a chance to speak on his own behalf. The court approved the plenary guardianship, and he says the next two years of his life became a living nightmare.

“I couldn’t see my friends, I couldn’t see my family, I couldn’t go for walks, I couldn’t do anything,” he says. “I was basically being held hostage.”

Lincoln-McCreight says he knew what was happening to him was wrong, but he was told there was no way out.

Then a friend’s mother told Lincoln-McCreight about an organization called Disability Rights Florida that might be able to help. Because his phone calls were being monitored, he hatched a plan: He asked his caseworker for money to buy a book, and when he got it, he used it to buy a burner phone instead. Then he hid in a closet and placed the call. Through that call, he connected with Tampa lawyer Amanda Heystek, and together they successfully challenged the guardianship, winning the restoration of Lincoln-McCreight’s rights in 2016.

Today, Lincoln-McCreight lives independently, holds a security officer license and a CPR certification and works full time in access control at a local country club.

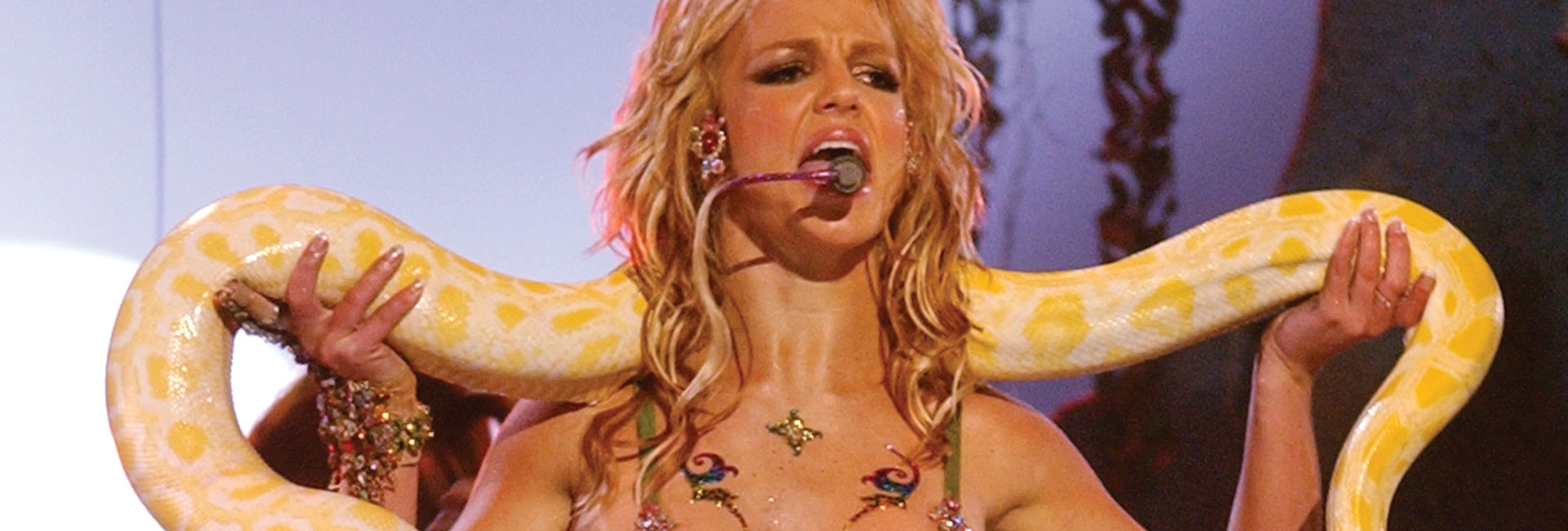

He also has become a passionate disability rights advocate, working with I Decide Florida for guardianship reform, and he co-authored an op-ed for the Tallahassee Democrat in July called “What happened to Britney Spears also happened to me—in Florida.”

He follows Spears’s case intently. “I look at her story, and it’s a spit-image of what I went through,” he says.

Spears’s case—and the corresponding #FreeBritney social media movement—brought national attention to a sometimes sinister system that has escaped scrutiny for decades, despite efforts by advocacy organizations and the bar to create more oversight.

For most of the past 13 years, every aspect of Spears’ life was controlled by her father, along with a team of doctors, lawyers, managers and minders. But for years, dedicated fans were suspicious about the conditions of Spears’ conservatorship, and their ongoing efforts to call attention to her case eventually paid off.

It all started in 2008 when a Los Angeles Superior Court commissioner granted her father, Jamie Spears, a temporary emergency conservatorship over her person and property after apparent mental health crises. Two months before the conservatorship was set to expire, the court cemented its terms, allowing it to last indefinitely.

But in 2020, Spears began a series of court actions challenging her conservatorship. During a June hearing, she described her life in harrowing detail.

She couldn’t freely access her passport, credit cards or cellphone, she alleged.

She couldn’t change her clothes without supervision at times, couldn’t leave her house without permission, and she couldn’t say no to work, medications, treatment or even to a dance move.

“I just want my life back. And it’s been 13 years. And it’s enough,” she told the court. “I deserve to have a life.”

(Jamie Spears’ role as conservator of his daughter’s estate was suspended in late September, and a judge was scheduled to consider whether to terminate Britney’s conservatorship in November.)

Spears isn’t the only celebrity whose controversial guardianship is making the news.

Trailblazing African American actress Nichelle Nichols, known to generations of TV viewers as Lt. Nyota Uhura from Star Trek, sits at the center of a three-way struggle between her former manager, a friend and her son. Nichols was diagnosed with dementia, and in 2019, her son, Kyle Johnson, was appointed conservator of her estate and person. Since then, he has moved the 88-year-old to New Mexico to live with him and sold her LA home.

Nichols’ former manager Gilbert Bell and a friend, Angelique Fawcette, have separately objected to Johnson’s control, and Fawcette has claimed she has been denied visitation. “She’s not getting the life that she wished for,” Fawcette told the Los Angeles Times in August. “She’s getting the life other people have chosen for her.”

Overprotective and abusive guardianships don’t affect just celebrities; these conditions are playing out across the country on a regular basis, ensnaring people regardless of their financial resources and name recognition.

People such as Jenny Hatch, a woman in Virginia with Down syndrome who lived independently, had a job and a supportive base of friends until her parents obtained guardianship over her in 2012 and sent her against her will to live in a group home, ostensibly for her own safety.

Or Coenia Schaefer, an 86-year-old woman in Oregon who lived alone in her own home and cared for herself and a menagerie of pets. A judge granted her son guardianship in 2001 based on a finding of dementia contained in a fill-in-the-blank report that had been completed by a worker with no formal medical training or college degree who interviewed Schaefer for just 90 minutes.

Both women challenged their guardianships in court and eventually won their freedom. But advocates for guardianship reform say such success stories are rare. Reforms must be made, they say, to ensure every state system successfully balances protection with self-determination.

Reform efforts date back to the late 1980s, when a groundbreaking series of articles published by the Associated Press in 1987 exposed egregious abuses nationwide. Lawmakers, lawyers and advocates stepped up, addressing the issue with working groups, new and revised state laws and improved model acts and standards.

In 1988, the National Guardianship Association was formed. Also that year, the ABA convened a meeting of the nation’s most noted subject matter experts to create recommendations for change. The meeting became known as the first National Guardianship Conference, and its efforts have been ongoing.

In 1997, the Uniform Guardianship and Protective Proceedings Act was updated to strengthen due process protections for people subjected to guardianship proceedings, and the Uniform Probate Code’s Article 5 was revised the following years to parallel provisions of the UGPPA. By 2012, nearly half the states had enacted all or a portion of the revised provisions. In 2017, the protections were further strengthened in the renamed Uniform Guardianship, Conservatorship and Other Protective Arrangements Act.

Between 2011 and 2020, “Many statutory changes have advanced guardianship reform: safeguarding rights, addressing abuse and promoting less restrictive options,” according to a December 2020 legislative summary from the ABA Commission on Law and Aging.

Progress is indeed happening, albeit slowly. “It’s like trying to push a cruise ship into a dock by nudging it in different directions,” says University of Missouri School of Law professor David English. He has been involved in reform efforts since 1987 and is the former chair of the ABA Commission on Law and Aging, the former drafting committee chair for the Uniform Guardianship, Conservatorship and Other Protective Arrangements Act, and the co-author of several treatises on estate planning and elder law.

Advocates for reform point to significant hurdles that still stand in the way of change. Guardianship remains under the purview of state law, with no federal standard, oversight or funding. In fact, the federal government doesn’t even know the scope of the guardianships that exist across the nation because there are no reliable statistics counting the number of guardianships, the amount of assets under guardianship or the number of guardianship challenges taking place across the country.

Undue influence

Help, however, seems to be on the way. Prompted by the Spears case, powerful lawmakers such as Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Bob Casey, D-Pa., recently called on the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Justice for information necessary to begin making changes, and there are bills currently before the House and Senate that call for both fixes and funding.

In addition to the high-profile Spears conservatorship battle, the movie I Care a Lot helped raise public awareness about flaws in the guardianship system, advocates say. The thriller follows a con woman who uses the guardianship system to institutionalize older adults while she steals their assets. After its February 2021 release on Netflix, it became one of the most-watched movies that month on the streaming service; by April, Netflix estimated it had been watched by 56 million households.

The COVID-19 pandemic also served to spark discussion about vulnerable populations, says Judge Lauren S. Holland of the Lane County Circuit Court in Eugene, Oregon. Holland, who was first elected to the bench in 1992, has been handling probate cases since 2001. Active in the ABA’s Commission on Law and Aging, she was a delegate to the Fourth National Guardianship Summit.

“Although people may not have been discussing guardianship specifically, the pandemic allowed the conversation about our elders and how we as a society and community treat our elders,” she says.

More generally, however, public opinion about people with disabilities has changed over time, as has the cultural expectation that people with disabilities must be protected, says Jonathan G. Martinis, senior director for law and policy with the Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse University. He heads the BBI’s efforts to ensure the receipt of appropriate supports and services for the older adults and people with disabilities. He also helped represent Hatch in her guardianship battle with her parents.

“It wasn’t until the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, passed 214 years after the Declaration of Independence, that we say that people with disabilities have the same rights as other people,” Martinis says.

One of the most significant reforms topping almost every guardianship reform wish list involves numbers—as in current, meaningful and comprehensive statistics involving all aspects of guardianship at the national level.

There were 1.3 million adults and $50 billion in assets under the care of guardians in the United States, according to a National State Courts estimate in 2016, but those figures were based on informed speculation.

This issue is now before Congress and government agencies in a number of ways, including a bipartisan bill called the Guardianship Accountability Act of 2021, in committee at press time, which calls for the creation of a National Online Resource Center on Guardianship and the development of state guardianship databases. The call from Sens. Warren and Casey seeks stepped-up data collection efforts, as does legislation introduced in July by Reps. Charlie Crist, D-Fla., and Nancy Mace, R-S.C., called the Freedom and Right to Emancipate from Exploitation Act, known as the FREE Act.

"If you want to understand a system, you have to be able to collect data." —Anthony Palmieri

Why is this data so important? Because it goes to the integrity of the entire system, says Anthony Palmieri, president-elect of the National Guardianship Association and a nationally recognized expert on guardianship fraud. Palmieri is the deputy inspector general and chief guardianship investigator for the clerk of the circuit court and comptroller of Palm Beach County, Florida.

“Any time you have a system without sufficient checks and balances and where one person doesn’t have all of their rights—they don’t have a voice and can’t defend themselves—it’s ripe for fraud,” Palmieri says.

“If you want to understand a system, you have to be able to collect data—data about the guardians, the attorneys, the petitioners—and give that data to the decision-makers so that they can make data-driven decisions, not knee-jerk decisions based on anecdotes,” he says. “The state needs to know this, or else how can we educate about guardianships and protect people under guardianships if there’s no empirical data to tell us what the problems are—and also to tell the story of those guardians who are doing honorable, ethical work?”

Data also affects resource allocation and the government’s ability to make policy decisions in response to outcomes and trends.

“When we go to the legislature to request resources to provide for necessary safeguards like audits, payment of court-appointed lawyers to represent protected persons, monitors for investigations and court oversight, the collection of data impacts that,” Holland says. “The legislators are certainly entitled to ask, ‘Well, how many cases are we talking about?’ And we are always in a better position to answer when we have more information.”

Guardianships have been described as both a gulag and a godsend, but practitioners say the most effective protections exist in the space between those extremes.

“Guardianship is not one-size-fits-all,” Palmieri says. “It can make sense in some cases—like when a person has Alzheimer’s and there’s family conflict around the decision-making—but it doesn’t make sense for younger people with intellectual disabilities, developmental disabilities or addiction.”

Karen Campbell agrees. As the executive director of the North Florida Office of Public Guardians in Tallahassee, she supervises the guardianships of more than 200 people living in 22 counties across North Florida. “I believe that on the spectrum of decision-making, guardianships are sometimes necessary,” she says. “We serve some people who are completely unaware of their surroundings and even need assistance turning over in bed. Our job in every guardianship is to help communicate the person’s preferences and actualize their life choices.”

Advocates say courts must explore less restrictive alternatives to full guardianship, and the ABA adopted resolutions in 2017 and 2020 urging this approach. The National Center for State Courts’ Center for Elders and the Courts has defined guardianship as a legal tool of “last resort,” and the Uniform Guardianship, Conservatorship and Other Protective Arrangements Act calls for an appointment of a guardian only if the needs of the person subjected to the guardianships “cannot be met by a protective arrangement or other less restrictive alternative.”

Despite these acknowledged best practices, 11 states and the District of Columbia still lack any reference to least restrictive alternatives in their guardianship statutes, according to 2018 statistics from the ABA Commission on Law and Aging. While the flip side of this statistic is encouraging—suggesting that the majority of state laws do recognize alternatives in some way—advocates say judges aren’t necessarily following the letter of the law. “Frequently, the law on the books is pretty protective of people’s rights, but in practice, we find that doesn’t really play out,” says Morgan K. Whitlatch, legal director of Quality Trust for Individuals with Disabilities in Washington, D.C. Quality Trust provides legal services to D.C. residents with disabilities and their families to promote alternatives to guardianship and the right to self-determination. Whitlatch also co-represented Hatch.

“There’s always been a gap between what the statute requires and how guardianship law is actually practiced,” English says, noting that even if a judge determines that a full guardianship is deemed necessary, limitations could be added such as a sunset clause or a mandate that a hearing be held after a later, specific date whereby the guardianship would have to be proved up again.

Alternatives to guardianship, such as powers of attorney and medical proxies, have long existed and continue to successfully help people requiring assistance (while simultaneously keeping them out of the legal system). But one of the most innovative new formats gaining traction in both advocacy communities and the legal system is called supported decision-making.

SDM mirrors the process by which most people make decisions: They consult friends and family, social services or other sources of support, then use that information to weigh the pros and cons of a particular decision to arrive at a choice. In the context of guardianship alternatives, SDM can range from a loose network of go-to advisers to a formal written agreement setting forth specific terms including revocation and termination. This extrajudicial solution means no laws or regulations are needed to set up a plan, and no lawyers are needed to craft an agreement. But Whitlatch says legal recognition would be helpful to demystify and legitimize the concept.

“What SDM looks like can change depending on the circumstances,” Whitlatch explains. “One can imagine a situation where someone requires greater support at one time, like in a mental health crisis, but not others. SDM can be adapted to the decisions you need to make in the short term and long term, across disabilities and even in cognitive decline.”

When Lincoln-McCreight successfully challenged his guardianship in 2016, he became the first person in Florida to terminate his guardianship in favor of an SDM. He says the arrangement was formalized via a written contract for the court; however, in practice, he says it’s more akin to “friends and family helping me out.”

Lincoln-McCreight’s lawyer says the arrangement is working. “He now makes his own decisions—some good, some not so good—but they are his, and he is happy,” says Heystek, a lawyer with Wenzel Fenton Cabassa in Tampa. When issues arise, she says, “he works through problems the way he should, by calling on his supports.”

Another critical component of guardianship reform involves making it easier—or at least possible—to challenge a guardianship and achieve a restoration of rights.

Laws that speak to these actions vary from state to state. For example, according to a 2019 report by the ABA Commission on Law and Aging, the guardianship laws in 13 states contain no mention of a right of appeal, either because the right doesn’t exist or because it’s assumed to be inherent as part of the Rules of Civil Procedure. Only eight states have statutes with specific procedures to appeal.

It’s also a mixed bag when it comes to the burden of proof. Some states put the burden of proof on the person seeking the guardianship, others on the person seeking relief, and the extent to which either must prove their case also varies.

But even meeting the lowest standard of proof can be problematic, lawyers say. For example, if a person under guardianship doesn’t have access to a phone or a computer, how can that individual contact a lawyer? If guardians control access to medical records, how can people under guardianship prove their medical or mental capacity? And if they’ve never been allowed to make decisions for themselves before, how can they show a court that they are capable?

“All in all, it’s like a spiral,” says Prianka Nair, assistant professor of clinical law and co-director of the Disability and Civil Rights Clinic at Brooklyn Law School. “Even with the best-meaning guardian, the system is coercive—it puts the person in the guardianship in a position where they may have to challenge family relationships, to challenge their own support.”

Mirroring the nightmare scenarios in Netflix’s I Care a Lot, Heystek says she once represented an older woman who didn’t even know she was subject to a guardianship “until the guardian showed up on her doorstep to come inventory her home and take her to an assisted living facility.”

Then there’s the problem of money. Statistically, people with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty and face barriers to finding and retaining employment, Nair says, making it difficult for them to hire a lawyer. And having money can be very necessary because some states require the person subject to the guardianship to pay the bills and fees—even if that person has received no notice of the proceeding or doesn’t hire a lawyer for themselves. “You can be forced to pay for the privilege of losing your rights,” Martinis explains.

One of the key barriers to challenging guardianship is knowing that it’s possible. That’s according to a study on the restoration of rights conducted by the ABA Commission on Law and Aging in 2013-2014. This happens because there’s no universal requirement for courts or guardians to regularly inform the people subject to their control that they have the right to seek restoration.

Ultimately, the hope is that everyone living under an unnecessary or repressive guardianship will have the opportunity to reclaim the right to live a fully actualized life to the fullest extent possible, and those who require support will receive it in a way that works best for them.

Thanks to a movie, a pop star, a pandemic and the passage of time, that hope—advanced by tireless efforts of visionary lawyers, lawmakers and advocates—may actually happen.

Jenny B. Davis, a former practicing lawyer, is a professor of practice at Southern Methodist University.

This article was originally published in the December 2021-January 2022 issue under the headline, “Legally Bound: Guardianship battles in the spotlight spark new calls for reform.”