Dec. 2, 1892: Grand jury indicts Lizzie Borden

The History Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

In November 1892, Fall River, Massachusetts, was an unremarkable New England mill town with a very remarkable problem: What to do with Lizzie Borden?

Late in the morning of Aug. 4, the body of Andrew Jackson Borden, a prominent local banker and mill manager, was found hacked to death in the parlor of his house at 92 Second St. Perhaps a half-hour later, the body of Abby Borden, his second wife and Lizzie’s stepmother, was found in a very similar condition in an upstairs guest room.

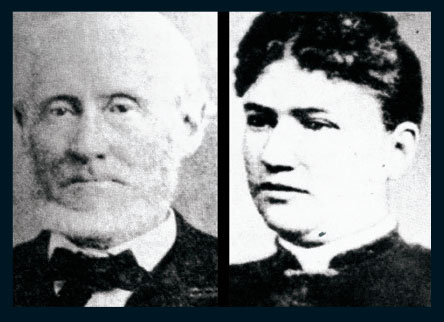

Dec. 2, 1892: Victims Andrew and Abby Borden. Photos by the the History Collection/Alamy Stock Photo.

At first, police suspected a Portuguese laborer turned away earlier by Andrew Borden unpaid for some work at the house. But the more they spoke with the 32-year-old Lizzie, the more the police came to suspect an answer closer to the Borden household. It had been Lizzie who had discovered her father’s body and sounded the alarm to housekeeper Bridget Sullivan, who had been washing windows that morning. It was Sullivan, along with a neighbor, who found Abby’s bloodied body upstairs.

Although the murders had evidently occurred over a span of 90 minutes, neither woman claimed to have seen or heard anything unusual. The problem was that there was scant physical evidence linking anyone to the spectacularly bloody murders, and police suspicions hinged on a string of circumstances gleaned from Lizzie’s sometimes-varying accounts. Even worse, Lizzie’s accounts seemed suspiciously detached, as when she corrected an investigator who inquired about her relationship with her mother: “She is not my mother,” Lizzie interrupted. “She is my stepmother.”

At the coroner’s inquest, actual evidence continued to be elusive, but so was Lizzie’s testimony: Her answers were short and often argumentative. She hadn’t realized her father had returned from an errand. When he did, she must have been in the barn searching for fishing sinkers. After finding his body, it never occurred to her that her stepmother might be in danger. Abby had left, Lizzie thought, summoned by a mysterious note.

But there was no note. Abby was still at home with 19 hatchet-like wounds in the back of her head. And on Aug. 11, one week after the murders, Lizzie Borden was arrested.

The Borden home is now a museum and bed-and-breakfast. Photo by Franck Fotos/Alamy Stock Photo

But the lack of physical evidence (or even an obvious motive) plagued prosecutors, and by the time a Bristol County grand jury was empaneled Nov. 7, the case seemed in limbo. Shortly before the grand jury was scheduled to deliver its report, neighbor Alice Russell shared a story she hadn’t previously told investigators.

Two days before their murders, Abby and Andrew Borden suffered severe stomach cramps, and Abby suspected poison. The night before the murders, Lizzie had acknowledged that possibility, telling Russell she feared another, more violent attack from some of her father’s business associates. More damning, Russell testified she had encountered Lizzie in the Borden kitchen three days after the murders burning pieces of a blue corduroy skirt she claimed had been ruined by paint. The grand jury had heard enough, and on Dec. 2, 1892, Lizzie was indicted for murdering her father with “10 mortal wounds” to his head.

But at her trial in New Bedford for the killings the following June, the lack of physical evidence continued to haunt the prosecution. Lizzie’s lawyer, George Robinson, was an experienced trial attorney and a former governor of Massachusetts. Robinson’s methodical cross-examinations undermined the circumstantial case against her. Her detachment was attributed to morphine sedation by the family doctor.The skirt-burning was dismissed by its obviousness and boldness. And on June 20, 1893—absent motive, serious blood evidence or even a weapon—the all-male jury acquitted her. Though it seemed no one else could have done it, many considered the outcome a remarkable exercise in the rule of law.

After her trial, Lizzie Borden continued her life in Fall River without controversy until her death at age 67. She was buried in the family plot, adjacent to her father, mother and, of course, her stepmother.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.