Feb. 11, 1812: Gerrymander's first sighting

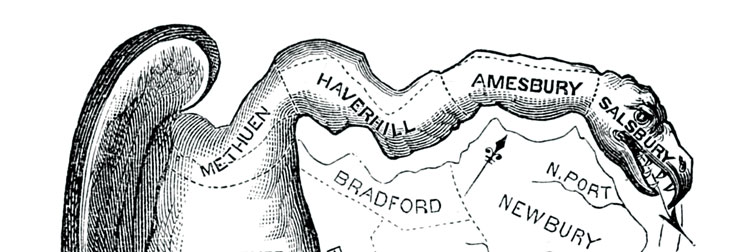

This cartoon map got its “Gerrymander” monster name upon publication in the Boston Gazette in March 1812. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

An unusual Boston Gazette article in 1812 announced that a monster had been discovered in nearby Essex County. The piece quoted a “Dr. Watergruel,” who deemed it to be a species of salamander and proposed it be named after Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry.

A drawing of the “salamander” was, in fact, a cartoonist’s depiction of a map of a senatorial district Gerry signed into law on Feb. 11, 1812. The state’s Democratic-Republican legislators had designed the map to enhance their election prospects. Senatorial districts, once confined to county lines, became intentionally amorphous, diluting the support of rival Federalists while consolidating clusters of the ruling party’s likely voters.

The aging Gerry was also a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a proponent of the Bill of Rights and a Democratic-Republican partisan. Though likely unfair to his actual contribution, the article dubbed the monster a “Gerrymander,” forever linking him to a long-standing exercise of political power.

In the two centuries since, the power of state legislatures to apportion political jurisdictions—including congressional districts—has been repeatedly challenged in the courts. Just as often, the courts have been reluctant to enter what they consider a purely political process. As a result, state legislatures have shown little aversion to “packing” and “cracking,” the same tools of voter concentration and dilution employed in Gerry’s time.

Gerrymandering helped rural populations dominate dense urban centers, and the courts would abide. In 1946, Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote, by entering the “political thicket” of apportionment disputes, courts would be forced to choose one theory of representation over another—a course he thought was constitutionally unwise. “For want of equity,” Colegrove v. Green let stand an Illinois congressional districting map in which the largest district served a population eight times that of its smallest.

But by the early 1960s, the civil rights movement began to expose the role of redistricting in the maintenance of racial inequality, and a series of U.S. Supreme Court cases began to address apportionment and gerrymandering as more than purely political.

Justice Hugo Black. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

After 1901, for example, the Tennessee legislature never bothered to redistrict, although the state constitution required it every 10 years. By 1960, the state’s eligible voting population had grown by 325 percent, and its largest state House district was 18 times as populous as its smallest. The resulting case, Baker v. Carr, took two oral arguments and 11 months of deliberation to put Frankfurter in the minority and make redistricting issues justiciable—at least regarding race.

In Georgia, rural control was particularly disparate. Like many Southern states, it was overwhelmingly Democratic at the time; and party primary elections decided, in effect, who would be elected in the fall. But under a “county unit system” created after Reconstruction, primaries were decided not by an overall popular vote but by units earned by winning the vote in each of 159 counties—an overwhelming advantage for rural voters.

Moreover, Georgia’s 10 congressional districts, last apportioned in 1931, were weighted heavily against the state’s urban population. By 1960, the 5th Congressional District centered in Atlanta represented 823,680 residents, more than twice the 349,312 district average.

In Wesberry v. Sanders, decided Feb. 17, 1964, a three-judge federal trial panel rejected a challenge to Georgia’s congressional districts, invoking Frankfurter’s “want of equity” in Colegrove. But the Supreme Court continued in Wesberry to change the rules when gerrymandering was implicated by race. Echoing the phrase that would be used in Reynolds v. Sims four months later, Justice Hugo Black quoted Gerry’s patron James Madison: “Who are to be the electors of the federal representatives? Not the rich more than the poor; not the learned more than the ignorant; not the haughty heirs of distinguished names more than the humble sons of obscure and unpropitious fortune.”

Black noted: “Readers surely could have fairly taken this to mean ‘one person, one vote.’ ”

This article was published in the February 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "A Move Toward ‘1 Person, 1 Vote.’"

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.