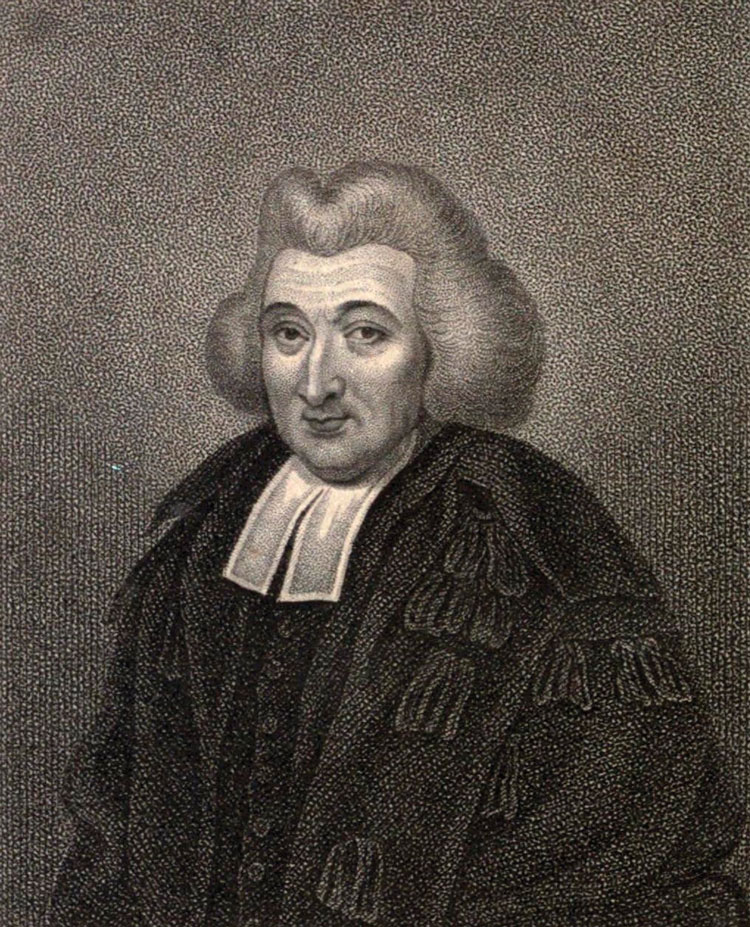

George Campbell on eloquence, analogies and how to handle a hostile audience

Photograph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Garner: Here we are 242 years after you wrote your Rhetoric, and it seems that many people aren’t bothered by a speaker’s impaired morals—not, that is, if they belong to the same political party. Our nation has become astonishingly divided and partisan.

Campbell: If the speaker and the bulk of the hearers belong to contrary parties, their minds will be more prepossessed against the speaker, though his life were ever so blameless, than if he were a person of the most flagitious [villainous] manners, but of the same party. This holds true for all parties, religious and political. This difficulty even the divinest eloquence will not surmount.

Garner: That’s a depressing thought.

Campbell: The more gross the hearers are, the more susceptible they are to such prejudices. Nothing exposes the mind more to all their baneful influences than ignorance and rudeness; the rabble chiefly consider who speaks, people of sense and education what is spoken.

Garner: How should a speaker handle the hostile audience?

Campbell: When the opinion of the audience is unfavorable, the speaker must be much more cautious in every step he takes to show more modesty and greater deference to the judgment of his hearers; perhaps, in order to win them, he may find it necessary to make some concessions in relation to his former principles or conduct—so that, like men of judgment and candor, they would impartially consider what is said and give a welcome reception to truth, from whatsoever quarter it proceeds. Thus he must attempt, if possible, to mollify them, gradually to insinuate himself into their favor, and thereby imperceptibly to transfuse his sentiments and passions into their minds.

Garner: I suppose it’s very different with a receptive audience.

Campbell: When the people are willing to run with you, you may run as fast as you can, especially when the case requires impetuosity and dispatch.

Garner: What special challenges do lawyers face as advocates?

Campbell: We know that the lawyer must defend his client and argue on the side on which he is retained. We know also that a prior application from the adverse party would probably have made the lawyer employ the same acuteness and display the same fervor on the opposite side of the question. This circumstance, though not considered a fault in the character of the lawyer, but instead a natural and ordinary consequence of the office, cannot fail, when reflected on, to make us shyer of yielding our assent.

Garner: What’s the most important thing you teach your students?

Campbell: Every sentence ought to be clear. The effect of all the other qualities of style is lost without this. Whatever is the ultimate intention of the orator—to inform, to convince, to please, to move or to persuade—still he must speak so as to be understood, or he speaks to no purpose. He may as well declaim before his audience in an unknown tongue.

Garner: Is it possible to be too clear at times?

Campbell: In what we read, and what we hear, we always seek for something in one respect or other new, which we did not know, or at least attend to, before. The less we find of this, the sooner we are tired. Superfluities are apt to disgust us quickly. The reason is not because anything is said too clearly but because many things are said that ought not to be said at all.

Garner: You seem to assume an attentive readership. What about inattentive readers?

Campbell: With them—and they are a pretty numerous class—darkness frequently passes for depth. They regard clarity and superficiality as synonymous. But it is surely not to their absurd notions that our language ought to be adapted.

Garner: Indeed. Thank you for allowing us to time-travel to 1776 to hear your thoughts—surprisingly apt even today.

Campbell: I rather enjoyed it myself, Bryan. Do come read me again.

Perhaps I just imagined that last response. But the visit was memorable.

Bryan A. Garner, the president of LawProse Inc., is the editor-in-chief of

Follow Bryan Garner on Twitter @BryanAGarner.

This article was published in the February 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title “A Fireside Chat with George Campbell: Advice from an enlightened Scot about eloquence, analogies and how to handle a hostile audience.”