Features

Chicago teens tell how guns affected them and their neighborhoods

Cristie/Flickr Creative Commons

Though their family moved to Lansing, Illinois, a quiet community less than 20 miles from their old home, the girls still worry about guns on the streets. They hate the violence, but understand the need for people to protect themselves. Their father, 40-year-old train engineer Dorian Compton, has been a legal gun owner for about a decade. He keeps his 9 mm handgun and small pistol locked in a safe.

"You're responsible for providing protection to your family," says Compton, a gun rights advocate. "To think that that would have been limited or I wouldn't have been able to meet the same force with the same force would have been to me a little naive."

Still, the girls have seen enough violence that they're not so sure. As part of a generation of African-American children who have witnessed the scars marking the bodies and souls of friends and family, they are uncertain who should be trusted with carrying guns. "Even though it could protect me outside my home area, it's just too much to have another gun on the streets when so many people are preaching to get them off," says J'Doria, who turned 18 at the end of October. "A gun can be used to help or harm you. It's all up to the user and what their mindset is."

Whereas other communities across the country have experienced mass shootings of youths—Columbine, Colorado; Newtown, Connecticut; Isla Vista, California—Chicago's playgrounds have long been battlegrounds, surrounded by a steady stream of seemingly random shootings, drive-by attacks and armed robberies gone awry. Here, in neighborhoods like Gresham where many black families dwell, guns and gun violence are not philosophical exercises of the Second Amendment, but rather menacing facts of everyday life. As Barack Obama, then a U.S. senator, noted in 2007 at a South Side Chicago church: "Our streets have become cemeteries. Our schools have become places to mourn the ones we've lost."

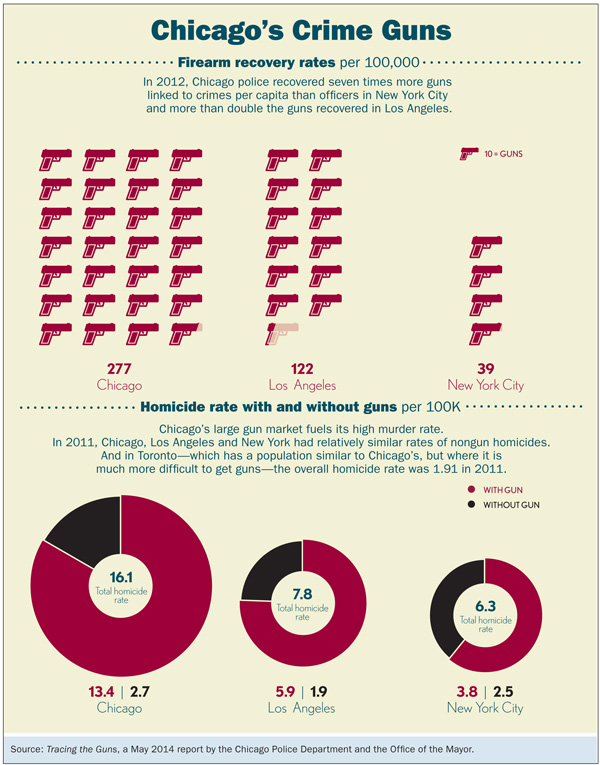

From 2008 to 2012, almost half of Chicago's 2,389 homicide victims were killed before their 25th birthdays, according to an April report by Amnesty International. A May report by the Chicago Police Department and Office of the Mayor says Chicago confiscates seven times as many guns used in crimes as New York City and more than double the number of Los Angeles.

The University of Chicago Crime Lab has found that shootings are concentrated in the city's most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, including the South and West sides. Seventy-five percent of the city's murder victims in 2012 were black or Latino, according to Amnesty International.

Until 2010, Chicago had one of the most restrictive municipal gun laws in the nation. In McDonald v. City of Chicago, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Chicago's wholesale curb on handgun ownership as an abridgement of the Second Amendment.

COLLABORATION AND DISCUSSION

The ABA Journal, headquartered in Chicago, worked with GlobalGirl Media, a nonprofit organization with a Chicago news bureau, to talk to residents about their attitudes toward guns and gun ownership. Under the direction of professional journalists, students like J'Doria and Jari discussed the topic in neighborhoods most affected by gun violence. Their subjects—friends, neighbors and members of their own families—reflect the full spectrum of conflict: fear, resignation, grief, anger, confusion.For instance, the two interviewed their father about gun rights and gun ownership.

Compton describes for his daughters a "horrific" incident—a break-in at a previous residence—when he had to pull his gun on an intruder. Being armed in his own home helped to defuse the situation, Compton tells them.

"It wasn't necessary that I take his life to prove a point," he says. "I was actually able to put my gun back."

Jari, 16, admits that having a gun in the family home does make her feel safer. "I do believe people should have the right to own a gun—only for protection and reasonable self-defense," she says. "This is because not everybody uses guns to harm one another."

Safety and proper training have not always been important to him, Compton allows. As a youth on the South Side, the first thing he learned about the weapons was how to put a bullet in a clip and how to squeeze a trigger.

"I've had friends who had died from the hands of guns," Compton says. "Just watching their parents grieve from a loss of a child is probably the most hurtful thing I have experienced."

Now, as a veteran firearm owner, Compton takes his weapons out every week, removes the bullets, and cleans and oils the guns. He trains his five children in gun etiquette, issuing safety tips that sometimes seem to contradict reality: "Never touch a gun" and "Never point a gun at anyone."

"You have to respect 100 percent everything there is about a gun," he says. "If there's a possibility that something could go wrong, it will go wrong."

And a lot goes wrong when it comes to guns in Chicago, says Harold Pollack, co-director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab, a nonprofit research group that aids government agencies and other organizations in developing approaches to reducing violence. Although the homicide rate is down overall over the last two decades, the city's problems remain serious, he says.

"Chicago does have markedly higher homicide rates than Los Angeles or New York. We have more homicides than New York, although New York is more than twice the size. That's a big problem," Pollack writes on the Incidental Economist blog.

Alexis Smith: "Guns promote violence. I would never own a gun." Photo by Bob Stefko.

EXPERIENCES AND OPPOSITION

Nineteen-year-old Alexis Smith is firm in her feelings about guns. "Guns promote violence. I would never own a gun because I hate them," she says. Alexis lives with her grandmother, Carol Smith, in the Humboldt Park neighborhood, about 17 miles northwest of the most statistically dangerous part of town. But Humboldt Park has as many violent crimes in a one-month period as Auburn Gresham, according to 2014 City of Chicago data.On one occasion, Smith dodged bullets on her front porch while waiting for Alexis to return from school. A shooter hid behind a car in front of her house and started firing toward a nearby intersection, Smith reports. Though she wasn't shot, she fell trying to run to safety.

But Smith's most enduring memory of gun violence is her daughter's 1996 suicide.

"I didn't think she would use a gun," Smith says, still shaken. "It really affected my family deeply."

Upon hearing the news of her daughter's death, Smith threw the phone, falling to the kitchen floor: "It took me a while. [I was] saying this is not real. My baby is not gone. This is not happening."

The experience, however, has not made Smith as absolute as her grand-daughter in opposing the Second Amendment. She believes in a citizen's right to own a gun, but laments how firearms end up in the wrong hands.

"Guns to me is just bad news," she says.

Until the July 2013 passage of the Firearm Concealed Carry Act, Illinois had stood as the last state to prohibit citizens from carrying concealed weapons. A 2012 ruling by the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Chicago in Moore v. Madigan ruled the state had failed to justify having "the most restrictive gun law of any of the 50 states."

Under the law's provisions, applicants must be 21 and they must hold a Firearm Owner's Identification card. Illinois State Police have up to 90 days to approve or deny FOID applicants. In addition, concealed arms are banned in schools, public parks, government offices and hospitals, as well as businesses where alcohol sales make up more than half the revenue.

By May this year, nearly 40,000 concealed carry licenses had been approved—an 800 percent spike from an initial February report by the Illinois State Police following the law's enactment.

Only 10 percent of concealed carry applications were granted in the first wave, but after less than three months, 60 percent of applicants were to receive their concealed carry cards in the mail. Illinois legal gun ownership has grown more than 15 percent from 2013 to 2014.

In Cook County, the state's most populous county and home to Chicago, only about 7.7 percent of residents have FOID cards, based on 2013 U.S. census estimates. Elsewhere in the state, firearm ownership is higher: More than 36 percent of all residents in the state's least populous county, Hardin—which includes part of the Shawnee National Forest—are card-carrying gun owners.

The McDonald case, which ended a nearly 30-year ban on handgun ownership in Chicago, was brought by Otis McDonald, a former maintenance engineer at the University of Chicago. McDonald, who died earlier this year, lived in Morgan Park on the far south end of Chicago. Like Compton, McDonald thought he should have the right to defend himself in what had become a troubled neighborhood. In an interview with the Chicago Tribune, McDonald argued that the effect of the gun ban on him, as an African-American, had the same effect as the "black code" restrictions against firearm ownership by free blacks in what once were the slaveholding states.

One of McDonald's supporters, Richard Pearson, argues that the Chicago handgun ban may have actually exacerbated the city's gun violence problem.

"The city made its own problems with gun violence by prohibiting handguns," says Pearson, president of the Illinois State Rifle Association, an affiliate of the National Rifle Association. "They wouldn't allow people to even register their firearms in the city."

"The people who are finally being heard from are legitimate gun owners, people who could own a firearm," Pearson adds. "They were ridiculed and belittled for being gun owners for years."

Itzayana Juarez, 17: "I'm not against guns because I think they can be useful. … But in my neighborhood, where there's kids, it's not necessary." Photo by Bob Stefko.

PERIL AND PRESSURE

In the Hermosa neighborhood of Chicago, where 17-year-old Itzayana Juarez lives, there is no ridiculing of those who possess firearms. Spasms of gun violence create a fairly constant sense of danger, even during the lulls."There are times when it gets really bad, and there's times when nothing really happens. ... Right now, there has been shootings," Itzayana says on a weekend during a study break for the ACT college readiness test. She wants a career as a grade-school teacher.

Hearing gunshots daily, Itzayana varies her route to school, at times opting for the longer walk for safety reasons. Her classmates over the years have joined gangs, she says.

One of Itzayana's close friends, who faced problems at home and felt pressured to join a gang, killed himself in September last year. "Nobody really knows where he got the gun," she says. "One thing led to another, and I guess he couldn't take it anymore."

When she was 12, Itzayana also witnessed the shooting of a kid outside a convenience store. Police and an ambulance arrived in time, she remembers, and the victim survived.

"I am not against guns, because I think they can be useful at times. But in my neighborhood, where there's kids, it's not necessary," Itzayana says. "We can't even walk out because we're afraid that you're going to shoot at us or something like that."

Among those interviewed were two young men who say they regularly carry illegal firearms as a matter of personal protection. Although both claim not to have gang affiliations, they say personal experience has provoked them to arm themselves. They asked not to be identified by name for fear of reprisals.

"I don't want my moms crying on my closed casket," says one high school sophomore, who has a handgun a friend gave to him. He also admits to having a criminal background. "You never know who just gone decide to run up and shoot you, and if that happens, you have to be ready."

He says there are times when it doesn't matter whether you are armed or not. He describes an incident in which a "dude" unexpectedly put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. The clip got stuck.

"My heart got to beating real fast, and I was so scared at that moment," the teen says. "But I wasn't gone show that I feared him at that point."

"I carry illegal guns because ain't nobody safe in these streets," says the other armed teen. "Nobody."

Like his friend, the high school sophomore had a gun pulled on him while walking to a park. He says he now has a stolen handgun and a rifle.

"I can't even lie. Guns scare me," he says. "To be honest, my intentions would never be to kill someone."

Click to watch interviews with some of the people in this story in this video produced by GlobalGirl Media.

The false empowerment of gun possession by children scares people like Tom Vanden Berk, a Highland Park, Illinois, resident whose teen son was shot and killed by another teen at a party 22 years ago. "Kids shouldn't have access to such dangerous weapons that could mutilate other kids so easily," Vanden Berk says. "Every gun starts out legal. Let's keep them legal."

Vanden Berk, who spoke to the ABA Journal on the anniversary of his son's death on April 25, has spearheaded a new political action committee in Illinois. One of his goals is to have a comprehensive registration and licensing system in Illinois for tracing guns.

"I thought [gun violence] happens to those kids who were in impoverished areas, who were close to gang violence," Vanden Berk says. "I just never expected to be a victim of it."

Yet, says Colleen Daley, executive director of the Illinois Council Against Handgun Violence, gun violence affects everyone. "A gun doesn't know if you're black or white, or if you're rich or you're poor."

Illinois Sen. Dan Kotowski, a Democrat who works on gun-related policy and serves on the Senate's Criminal Law Committee, was held up at gunpoint more than 20 years ago while waiting for the El on the South Side.

"These guys came up to me, put a gun in my back," Kotowski says. "The other guy took my money and my favorite coat and a John Steinbeck book, and he threw it at me. Obviously he didn't like my taste in literature, but I was very scared."

A kid came up to him and asked if he was all right, Kotowski remembers. "I said, 'No, man, I'm really scared.' "

The incident helped inform his interest in gun control, for which he has become a well-known advocate. Last year, Kotowski brought parents of the Sandy Hook massacre victims to speak to Illinois lawmakers as part of his opposition to the concealed carry bill. Now, after the legislative loss, Kotowski is changing his strategy.

"My intention is to make it about the industry," Kotowski says. He is targeting gun manufacturers like Smith & Wesson, whose affordable handguns were the most confiscated firearm in Chicago crimes during 2012 and 2013 (next were those by Sturm, Ruger & Co.). He finds it confounding that the Consumer Product Safety Commission has rigorous standards for the manufacture of teddy bears and other children's toys but does not regulate guns for safety.

"Crime and tragedy is good for business. It always has been," Kotowski says.

But to Pearson of the Illinois State Rifle Association, money isn't driving the dispute on guns: "We have a lot of members, but we don't have a lot of money. We have a lot of people who want to defend themselves. That's what makes us strong."

This article originally appeared in the November 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: "From Playgrounds to Battlegrounds: Chicago teens tell how guns affected them and their neighborhoods."

Sidebar

Coping with Guns Inside and Outside Chicago

The city of Chicago and the state of Illinois have long been battling the rise in the number of handgun crimes. Recently, each has had to modify its laws after federal courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, described some regulations as too stringent.As a result of a court order, in June the Chicago city council unanimously approved a law that would allow the resumption of gun sales in the city but with restrictions that require videotaping of purchases and limiting sales to one per month per buyer.

The new law comes after the 7th Circuit invalidated the city's longtime ban on gun sales in January. The court gave the city six months to come up with its own gun store policies.

The law requires a 72-hour waiting period to purchase handguns and a 24-hour wait to buy rifles and shotguns. In addition, gun store employees have to undergo background checks and sellers need to prepare quarterly inventory audits and make store records available for police inspection. Gun sales are prohibited within 500 feet of schools.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel called the ordinance "tough, smart and enforceable."

After lifting the handgun ban, Chicago saw a particularly violent year. In 2012, 86 percent of all Illinois murder victims were killed by gunfire. Chicago claimed a disproportionate number of victims that year, with more than 500 lives lost.

City officials also have to deal with the flow of guns into the city from outside. According to the May report Tracing the Guns (PDF), 60 percent of guns recovered in crimes in Chicago were first sold in other states.

While the study by the police department and the mayor's office shows that most of the firearms in Chicago's dangerous neighborhoods entered illegally through a small number of individuals, many originated from legal sources by swapping hands. The average time between the legal purchase of a gun and its use in a crime is about 11 years, according to Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives data released in June.

The state of Illinois has also modified its gun laws. In 2013, the state legislature passed a law requiring private firearms sellers to use the Illinois State Police's dial-up system to verify that the buyer is the holder of a valid Firearm Owner's Identification before making a transfer. The new law requires owners of firearms to report loss or theft of firearms. However, Illinois does not license or regulate firearms dealers or require firearm owners to register their individual guns.

» Return to the top of the article

Itzayana Juarez (left) and Alexis Smith (right) are both GlobalGirl reporters and contributors to this story.

GlobalGirls Get the Story

The ABA Journal sponsored the new media training of four teenage Chicagoans who contributed to the reporting of this story. The students are part of the nonprofit organization GlobalGirl Media, which works with young women from underserved communities around the world.The GlobalGirl reporters, who have grown up in some of Chicago's most dangerous neighborhoods, conducted video interviews with their family members about guns.

GlobalGirl contributors to this story were:

Itzayana Juarez, 17, who says she hears gun shots every day: "There's a park in front of my house, so it's like a constant battle over here." She witnessed a shooting as a pre-teen, and last year her childhood friend killed himself with a gun.

Alexis Smith, 19, who lost her aunt to a gun-related suicide. "I would never own a gun because I hate them," she says.

Teenage sisters Jari and J'Doria Taylor, who grew up among guns, as their father is a licensed Illinois firearm owner. "Some people cannot defend themselves with guns," 16-year-old Jari notes. J'Doria, 18, would like to see fewer guns on the streets, especially among her peers: "Teens should not be carrying guns at all. They should be finding something better to do."

From their Chicago news bureau, the GlobalGirls have reported on other community issues through multimedia storytelling, producing video features like Living Off Tips, in which they explore how low-wage, tip-dependent restaurant workers—who are predominantly women of color—make ends meet. The team also produced a three-part series of interviews with feminist activist Gloria Steinem.

» Return to the top of the article

Alison Flowers is a freelance journalist based in Chicago.